Changing public perceptions of mental illness

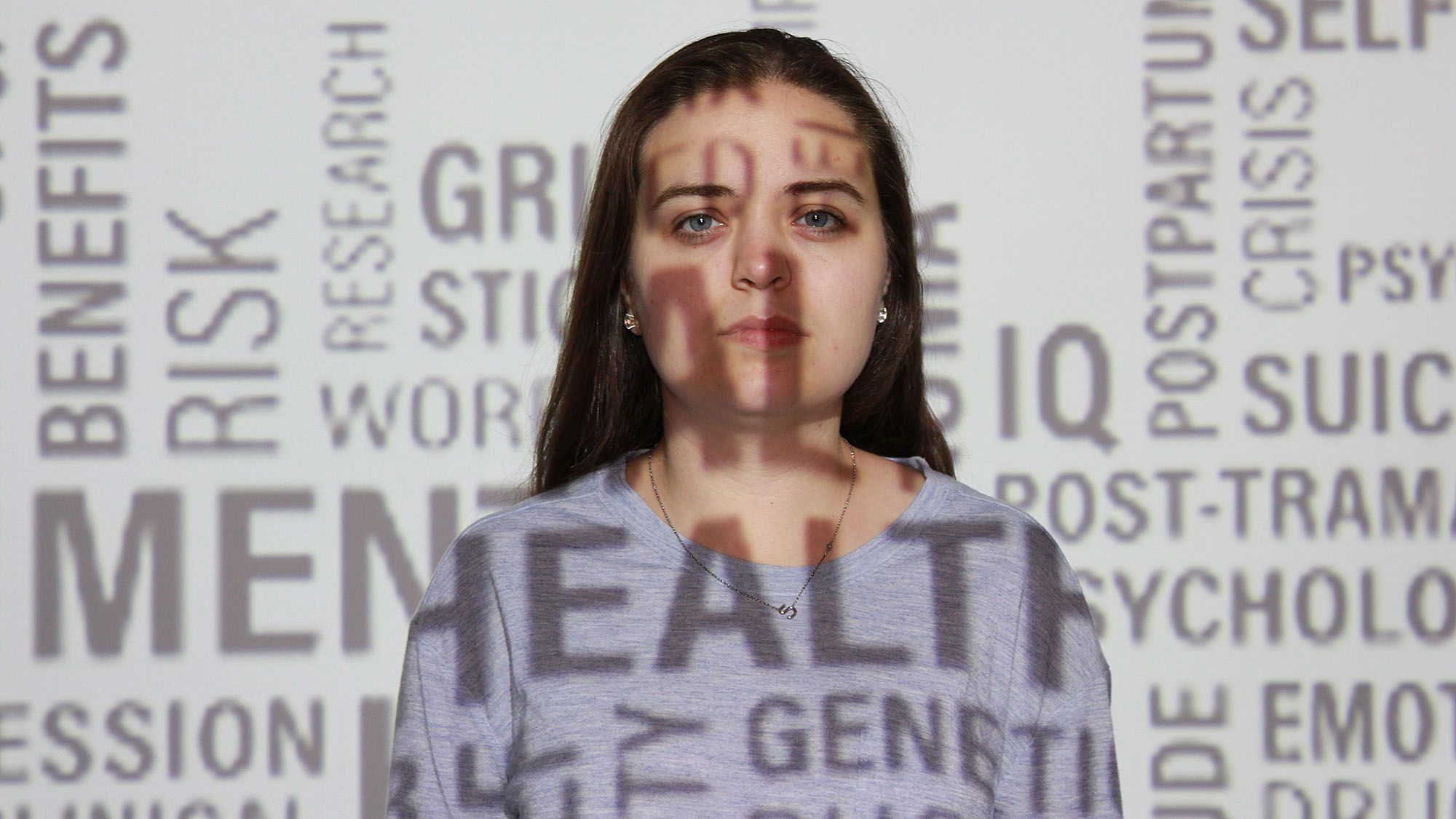

caption

A model is projected with words related to mental health.What journalists need to know before reporting

Allison Garber was diagnosed in her early 20s, with obsessive-compulsive disorder and general anxiety disorder. Garber was a university-educated, middle-class woman working a prestigious internship in Toronto. On the inside, though, she felt broken and lost.

“I was terrified, I was panicked,” she says. “I didn’t have anyone else to talk to besides my family. I look back really sadly at the internship. I basically had to lie and make up an excuse as to why I was ending the internship early.”

Garber was interviewed early in 2018 for the Bell Let’s Talk Day special. After the interview aired, her former boss said he wished he knew about her mental illness so he could have offered support. When she worked for him, 20 years ago, it just wasn’t something people talked about.

Although mental illness is being talked about more, it was still terrifying for Garber to tell her story to millions of people. “I was terrified about how I was going to be portrayed.”

Stigma starts here

According to the Mental Health Commission of Canada (MHCC), one in five Canadians — seven million people — will be affected by mental health in any given year. Jamie Livingston, a sociology and criminology professor at Saint Mary’s University in Halifax, says journalists could improve on mental illness reporting. However, there aren’t many journalistic sources offering guidelines for journalists to follow.

Michael MacDonald, a Canadian Press reporter in Halifax, is disappointed the Canadian Press Stylebook doesn’t have more information on the topic. The book features three-quarters of a page on suicide — about 260 words — but doesn’t mention reporting on mental illness in general. CBC and the Globe and Mail don’t mention mental illness in their reporting guidelines.

“It’s not doing any journalist any good by not providing them with some guidance, or even just a little bit of guidance — something, anything,” says MacDonald.

According to Livingston, large institutions such as media outlets have the power — whether they intend to or not — to influence people’s thoughts about mental illness. He says media coverage plays a large role in what people pay attention to and how to think or feel about it.

Sometimes reporting can reinforce public attitudes about mental illness, he says. This includes the stereotype “that people with a mental illness are dangerous and violent.”

MacDonald has written numerous stories about mental illness in his career. He focuses on not criminally responsible (NCR) due to mental illness cases. People can claim NCR in court to prove that they shouldn’t be held responsible for their criminal actions because of a mental illness. Some reporting stigmatizes these claims by portraying NCR as an easy way out, a way to avoid being charged. MacDonald wrote a story featuring Livingston’s video project on forensic mental health success stories. Livingston believes MacDonald is doing fair and just NCR reporting.

Through his reporting, MacDonald says he’s trying to portray NCR cases in a more positive light and works on “explaining exactly what’s going on when in fact someone with a mental illness comes into conflict with authorities or the law.”

MacDonald says reporters should do their best to follow the story and include all the intricacies. In most cases when MacDonald writes on an NCR story he follows it from beginning to end, writing dozens of stories detailing trials and inquiries. Although an NCR claim is often misunderstood, MacDonald hopes his reporting shows more accurate representations.

Mind your language

A large part of continuing mental health stigma in the news media is the language. A 2017 study in the United Kingdom notes secondary school children can identify 250 mental illness-related words. Of the words 70 per cent were negative, 30 per cent neutral, and none were positive.

Sheryl Boswell, executive director of Youth Mental Health Canada, says people with mental illness have their identity and experience challenged by language. She recommends using person-first language, which separates the person from a diagnosis. For example saying, “someone has bipolar disorder” over “someone is bipolar.”

“To say someone is bipolar is to say that’s all they are, and it’s still not recognizing them as a human being,” says Boswell. “Whether we use a noun or we use an adjective it’s the same thing — you’re reducing people down to a disability or an illness.”

Saying someone “is mentally ill,” according to some mental health advocates, has the same connotation of saying someone who has cancer “is cancerous.”

The “lived experience movement”, which values evidence gathered from the personal experience of mental illness, as well as from research, is important, Boswell says. It includes people living with mental illness in decision-making and other discussions — such as news representation.

“We don’t have a lived experience movement in Canada, and that’s a huge challenge to everything we do,” Boswell says. “Because we don’t have a voice, we’re not invited, we’re not respected in terms of our experiences. We should be leading and directing the change that’s needed in every aspect. If that happens, we define what we need in the media.”

caption

A name tag that says “Hello, I am not my mental illness”.Not one experience

Not everyone with a mental illness has the same experiences but sometimes it’s portrayed that way. Mental health advocate Ally Geist says news coverage focuses on “trendy” events such as awareness weeks and tragedies.

Media coverage of mental illness, according to Livingston, should become more extensive. Reporters should avoid reporting as if one person’s story represents all individuals’ stories. As mental illness gets reported on more it will create a “buffet of stories” people can read to get different perspectives.

Recovery and living with mental illness involves both positives and negatives. Mental health reporting should, according to Livingston, be “bringing in a combination of both.” But even when mental health perspectives are included it doesn’t mean the audience sees the whole picture, or even a true picture.

When Geist was 19 she modelled for a mental health awareness clothing brand, Wear Your Label, at Atlantic Fashion Week 2016. A reporter interviewed her about her experience living with an eating disorder. Geist was asked stigmatizing questions and felt tokenized by a journalist who was, according to her, “just looking for a headline or sound bite.”

Geist has continued to allow journalists to interview her because she’s hopeful things will eventually change. Still, talking about her eating disorder is something she finds extremely challenging and avoids bringing up in interviews because she’s afraid they’ll romanticize it.

She feels psychiatric labels are often used incorrectly, leading to misunderstandings. Headlines such as “Toronto mass shooting suspect struggled with psychosis, depression: family” can have mental illness dominate a discussion, and make it seem like all people with a mental illness are violent.

“When it comes to some negative event that’s happened in the world or in your community I definitely think it’s people’s first instinct to make mental health stand out,” says Geist.

Next generation

The next generation of reporters may be the best hope the mental health community has in stopping perpetuation of stigma.

A lack of research on mental health in Canadian media was recognized by Dr. Robert Whitley, an assistant professor of psychiatry at McGill University, about 10 years ago. So he, his colleagues and the MHCC conducted their own.

Between 2005 and 2015, Whitley’s research shows, reporting on mental illness improved, using a more positive tone and less stigmatizing language. Whitley thinks mental illness should be treated as an illness in media.

“Mental illness by definition is an illness and illnesses are not pleasant, whether it’s a physical illness or a mental illness,” says Whitley. “I think it’s important to communicate that.”

Whitley says there is always room to improve, and feels the next generation will do so. “The new generation of journalists coming through seem to be well primed, well educated, and interested in looking at the nuances of mental health, mental illness and people with mental illness.”

Allison Garber hopes things will continue to get better as more people — including her — begin to feel more comfortable discussing their experiences.

“In talking more about mental health,” says Garber, “I hope we don’t make it so people feel as though individuals with mental illness are not able to achieve the same success as other people.”

P

Patricia O'Halloran

B

Betty O’Halloran

H

Harold A Maio