Inattention

Dal psych research could help explain vehicle/pedestrian collisions

Research on visual attention has implications for drivers

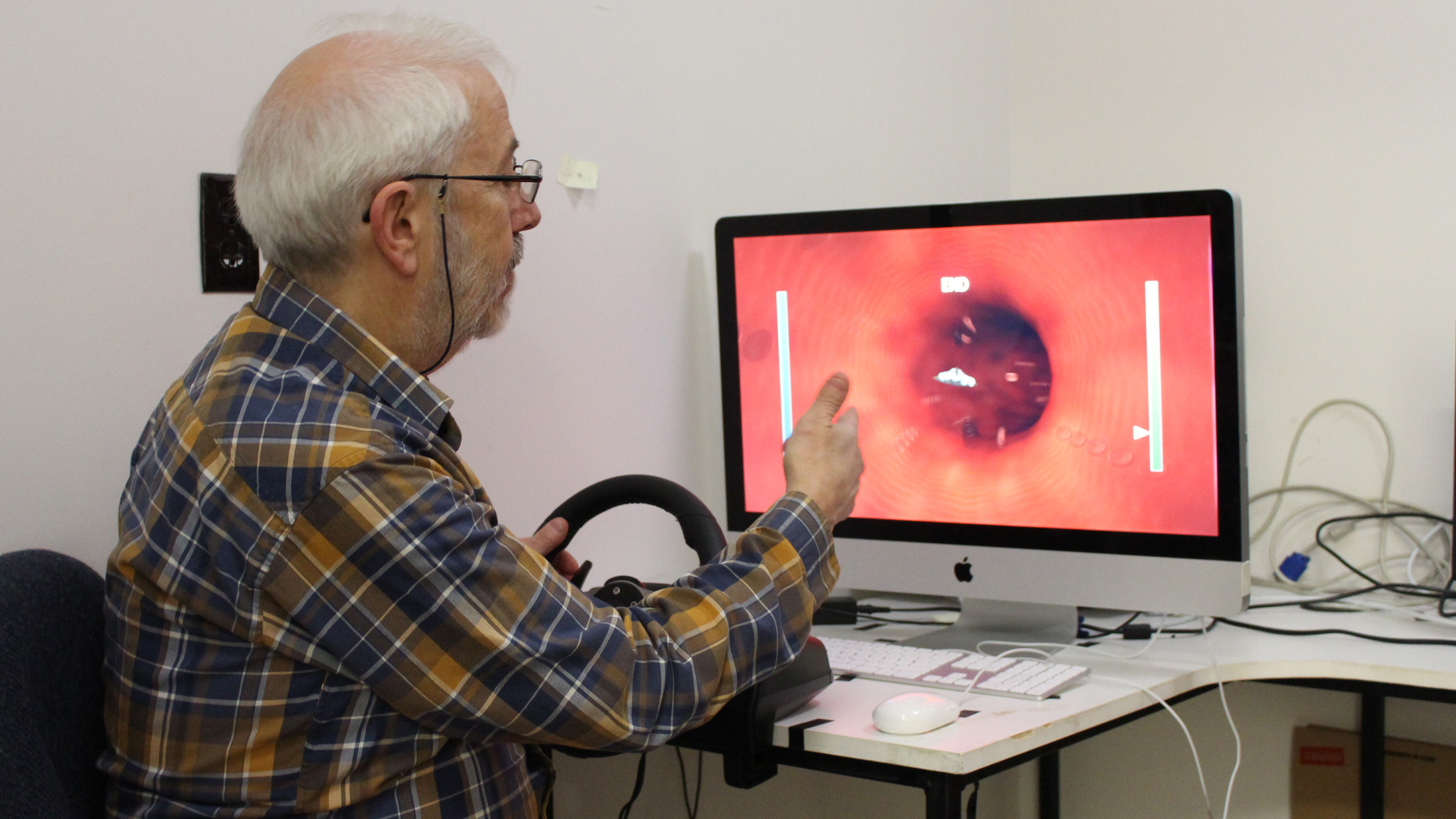

caption

Professor Raymond Klein explains one the experiments conducted in his lab

caption

Professor Raymond Klein explains one the experiments conducted in his labLast year there were 208 vehicle/pedestrian collisions in Halifax and more than half of those occurred at designated crosswalks. And that was an improvement from the previous year.

Psychological research conducted at Dalhousie University may offer some insight into why this happens.

Professor Raymond Klein heads up the cognitive science laboratory at Dalhousie—also referred to as the Klein Lab. Related stories

caption

Klein and student Colin McCormick calibrate an eye-tracking system for an experiment.The bulk of the research at the Klein Lab concerns a phenomenon of our visual attention called “inhibition of return.”

“It’s sort of a ‘been there, done that’ reflex,” says Klein.

When your eyes scan an area looking for something specific, they will avoid revisiting places that they have already searched.

“Normally, if you’re searching for something (…) in a visual environment, it would be more efficient not to go back to those places and to continue on to new places,” says Klein.

Klein speculates that the reflex evolved to help our ancient ancestors with foraging. Research by some of Klein’s colleagues in Israel suggest even fish exhibit this behaviour.

“Even though we’ve evolved to do this, it’s really relatively low-level mechanism,” says Klein.

The trouble arises when these automatic processes interfere with complicated tasks, such as driving.

Colin McCormick, an undergraduate student conducting research with Klein, agrees that the “been there, done that” reflex creates risk for pedestrians.

“If you’re on Spring Garden Road and (…) you look right and then you’re looking to the left (…) and you don’t see anybody (…) you’re not going to be as likely to re-attend to that location,” says McCormick.

“It’s going to be harder to spot somebody if they jump right out into the street,” he says.

“There’s always the possibility that you would not want this reflex to be in control,” says Klein, “It’s kind of operating all the time. And sometimes your intentions can override it.”

Taking control from your automatic systems requires more of your attention. And Klein is an advocate of dedicating more attention to driving.

A widely-reported literature review that came out of the Klein Lab in 2009 suggested that hands-free phones affect driving to the same degree as regular cellphones.

Klein points out that although we use our hands, feet and eyes to drive, they are all ultimately controlled by our mind.

“Since we drive with our minds, it is unwise when driving to allocate significant portions of our limited mental capacity to activities unrelated to driving,” Klein wrote in one description of the research.

caption

Klein regularly uses Where’s Waldo? to add a busy visual element to his attention experiments.McCormick suggests pedestrians take steps to protect themselves.

“(Inhibition of return) only lasts a certain amount of time. If pedestrians take the time, and make themselves noticed at the side of the road (…) they’re a lot safer off,” says McCormick.

Klein says further research should be done on the effect of inhibition of return on drivers.

“A real-world study would be warranted, based on the basic research that’s been done here,” says Klein.