Something in the water

caption

Thousands of Nova Scotians have a silent killer in their well water.

In Upper Clements, along Highway 1, a house sits back from the road.

It reveals itself at the end of a winding driveway, emerging from behind a cluster of trees. It’s been there more than 100 years, so time has washed over its floorboards and through its rooms. Gentle reminders of the past remain: family photos, knickknacks, and a door frame adorned with small, ascending ticks marking the heights of growing children.

For the last 15 years, Michelle McGowan and Michael Gunn have called this home.

The house is old, but one thing’s new: hidden out of sight underneath the kitchen sink, a series of cylinders is hooked up to a cooler-sized tank that further connects to a small faucet on the kitchen sink. It’s a water treatment system, meant to shield McGowan and Gunn from the cancer-causing arsenic that’s abundant in the water from their private well.

Along with Gunn and McGowan, almost half of Nova Scotia’s population uses a private well, and arsenic in the water isn’t rare. In fact, it’s the most common naturally occurring groundwater contaminant in Nova Scotia and a potentially deadly one.

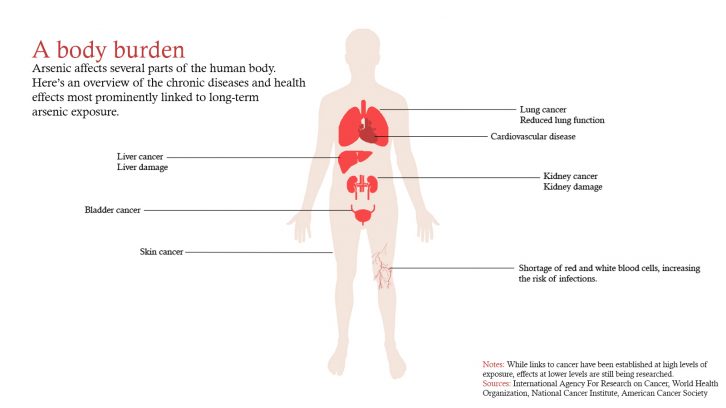

Arsenic is responsible for chronic diseases that cut thousands of lives short every year nationwide, especially in Nova Scotia, a province where the rate of arsenic-related cancers outstrips the national average. It’s been singled out by the World Health Organization as one of its 10 chemicals of major public health concern, and has been recognized by the federal and provincial government as a risk.

However, the province takes no hand in safeguarding private well users and imposes no regulations on their water safety. In the real estate market, it’s similarly “buyer beware” with no requirement on the seller’s part to test before selling. Banks only ask for water analysis if a mortgage loan is for new home construction.

When it comes to arsenic, learning, testing and treatment all happen on the well user’s own dime and time, and not only do few seem to take active measures to protect themselves, most don’t even know they should be worried. With researchers finding evidence of cancer risks at exposure levels well below what’s currently the recommended maximum, the number of Nova Scotians officially at risk is likely understated by a lot.

Getting Informed

Two years ago, McGowan was among those who had no idea there could be a problem. But then she read that the Ecology Action Centre, a Halifax-based non-governmental organization that focuses on environmental issues, would be holding workshops and information sessions on water safety in the Annapolis Valley, as far west as Berwick. After some persuasion on the part of McGowan, they extended that to Annapolis Royal, and as she listened to their presentation, she was dealt an angry shock – everything she was told, about arsenic, its presence in our groundwater, and what must be done to combat it, was news to her.

“I felt uninformed, when I had always gone out of my way to be informed,” she says. “I mean, I don’t have a science degree, so I joined sites so that I’d be informed. It was a fluke convincing the Ecology Action Centre to come down here.”

caption

Michelle McGowan teaches social studies in Annapolis Royal.McGowan had always considered herself vigilant about her well water’s safety. Bacterial contamination is the most common risk factor for well water, and basic bacterial tests can be purchased over the counter at local pharmacies and health centres. McGowan would use these to test every two years, and she says they’d always come back “clean, clean, clean”. After several all-clears, she ceased to test.

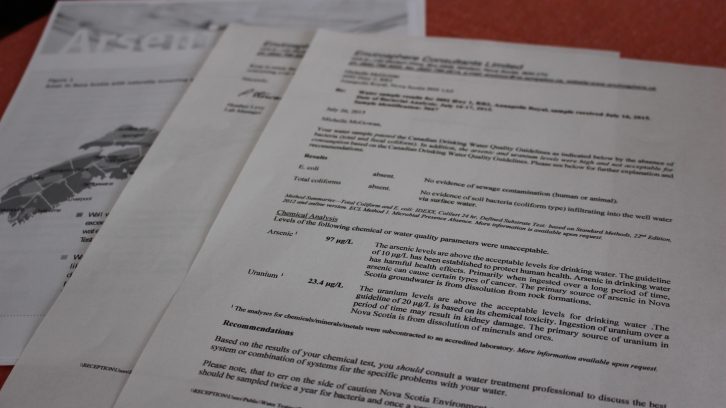

At the workshop, the Ecology Action Centre offered people testing kits for other contaminants such as arsenic and uranium. McGowan jumped at the opportunity, though she was confident in her previously stellar results. A week later, the report came back: her arsenic level was 97 micrograms per liter – almost ten times higher than the recommended guideline.

“When we found out, we went bananas; ire, rage, I had it all. I was so angry,” McGowan says. “I mean, I would have put something in right away had I known this would be an issue, right? ”

And as it turned out, Their well wasn’t the only one with arsenic above the guideline. Many of McGowan’s friends, colleagues and neighbours’ wells also had excessive levels of arsenic.

Well, Well, Well

McGowan and Gunn’s private well is one of thousands in the province. The Department of Environment keeps a well log, a database that records the location of wells drilled or dug since 1920 to 2014. Anyone can download it from the internet. It’ll tell you there are close to 96,000 domestic wells in the province.

The most common source of exposure to arsenic is ingesting contaminated drinking water and foodstuffs grown with arsenic-contaminated water. Arsenic is common in the rocks and soils of Nova Scotia, and some of it leaches into the groundwater. As the vast majority of wells constructed today are drilled wells, they reach more deeply than the dug wells of the past, bringing up groundwater instead of surface water. The province’s Department of the Environment keeps a map that details the likelihood of arsenic being present in your groundwater, with areas across the province classified as “likely” or “very likely,” with roughly two-thirds of the province’s landmass falling into the latter category. Layer it on top of the well log database, and you find that over 70,000 drilled wells are very likely to have arsenic. In this map, wells in the green areas are very likely to to have arsenic; the dots represent individual wells.

Arsenic is a human carcinogen, meaning it’s cancer-causing, and the federal government imposes a guideline level level of maximum allowable concentration that public water supplies can’t exceed. For private well users, that level is a guideline and therefore not enforced. The Guidelines for Canadian Drinking Water Quality have been published since 1968, and the guideline for arsenic was set then at 50 micrograms per liter (µg/L). As knowledge and measuring methods improved, the guideline has been steadily lowered and in 2006, it was adjusted to its current level at 10 µg/L. While it is unlikely to occur, municipal supplies found to have arsenic levels above the maximum allowable level of concentration must be treated.

So city-dwellers are protected. Provincial regulations prescribe their water be tested every two years, and treated if need be. Private wells, however, are unregulated. People are not required by law to test when the well is drilled, nor at any point after that.

A vast majority of new well users will test for bacteria and many will do a chemical test when the well’s built. Online pamphlets issued by the provincial government make clear the necessity to test for arsenic, and recommend that people do it every two years, but leave it there.

Whatever is in the water is a matter for the well owner. So, how concerned should they be? Is their vigilance required? What percentage of wells exceeds the limit?

Studies that look at arsenic exposure offer different answers, with some saying just under 10 per cent, others closer to 20, and some even reaching 40 per cent. The threat of arsenic’s presence might seem nebulous if you look at these numbers, but if you ask environmental experts, such is the nature of groundwater. You can’t know for sure which wells will have arsenic, and which won’t.

caption

The test results McGowan and Gunn received from Envirosphere Consultants, telling them of their exceeding arsenic levels.“It can be very localized. There can be two wells on the same property, and one can be fine and the other might not be,” says John Drage at Nova Scotia Environment. “But what we can say, is that on a geological formation basis, certain areas are more likely to have problems than others, so when you look at the statistics, you can see in some formations you may have 20 to 30 per cent of wells exceed the guideline; in other formations you may have less than five per cent.”

So the actual number of wells affected is unclear. But with close to 100,000 wells in the province and a conservative estimate of 10 per cent above the guideline, that’s roughly 10,000 wells.

Do the people who use them know?

See no evil, smell no evil

“To a lot of people, they don’t realize what could possibly be in their wells,” says Sam Reeves of the Bluenose Coastal Action Foundation, a group based on the South Shore that conducts workshops on water safety as part of its environmental work. “Things like arsenic, uranium and lead, those are types of things you can’t smell or taste, so a lot of people don’t suspect them to be in their water. But when you go and tell them that you could possibly have something such as arsenic that could be impacting their health, they’re quite surprised.”

Even for those who’ve heard of arsenic, misinformation is common. The Clean Annapolis River Project conducts an identical program to that of the Bluenose Coastal Action Foundation, and both groups’ presentations have had modest attendance. Organizers at the Clean Annapolis River Project say they’ve encountered the same lack of awareness, as well as those who were aware of the possibility of arsenic, but thought they had no recourse.

“A few people came, and they had just been under the impression that if you had uranium or arsenic in the water, there’s nothing you can do, there’s no treatment options available,” says Katie McLean of the Clean Annapolis project. “So they thought there was no point in testing for it.”

Darwin Seale of Envirowater Technology, a company that sells water treatment systems, can attest to the misinformed mindset.

“They’ve purchased bottled water for years and years and years, and they finally see us at a home show or something, and we ask them about their water, and they say ‘Ah, it’s terrible, it has arsenic in it,’” Seale recalls. “And we say ‘Well, you want to fix it?’ and they say ‘You can fix that!?’ So yeah, we run into that quite often.” Seale says his firm sold about 60 treatment systems in the past year.

The Nova Scotia government is aware of this knowledge gap.

As part of its ongoing focus on arsenic in groundwater, the provincial government undertook a study in 2014 together with Atlantic PATH, a health research group, that looked at the arsenic awareness and testing habits of Nova Scotians. Researchers interviewed well users about their testing habits, but also asked them about their confidence in the quality of their drinking water. They found confidence, but it was based on gut-instinct rather than evidence.

Sixty per cent of people interviewed said they had no or low concern when it came to the possibility of arsenic in their drinking water. When asked how often they tested, only 12 per cent said they tested once every two years. When quizzed on when to test, only eight per cent correctly identified the two-year guideline. As for personal risk of exposure compared to in the province at large, the study found a pervasive lack of concern when it came to local risk, as more than half of interviewees said they knew arsenic to be an issue in the province, but did not figure it to be a risk for them personally. Several even said they knew neighbours had found excessive levels of arsenic in their wells, but that this didn’t cause them concern about the integrity of their own.

Testing deficit

After an informal phone survey of water test laboratories around the province, the study’s findings don’t seem that far off. EnviroSphere, a firm based in Windsor that serves Hants, King’s and Annapolis counties, says it did 180 tests for arsenic last year. In 2015, it was 150. This is in an area with close to 20,000 wells that should be tested every second year, as per the guideline. At Nova West Laboratory on the South Shore, just under 300 tests were done in 2016, the vast majority of them from registered sources such as restaurants and hospitals, who are required to test. However, the tests that would come back with exceeding levels of arsenic were much more likely to come from the minority of private wells.

A disincentive could be the difficulty of getting tested. There are only five labs in the province that do tests for chemicals such as arsenic, and three of those are in the Halifax region. An additional two will sub-contract arsenic tests, meaning they’re sent to Halifax for analysis. Samples must be delivered in special bottles to be picked up, and samples must be treated carefully. The hassle can turn some people off, says Katie McLean of the Clean Annapolis River Project.

“It can be a bit of a challenge for people. After you collect your sample, you have 24 hours to get it to a lab, and it needs to be maintained at 10 degrees or lower, but not freezing,” she says. “So for people who don’t live within close driving access to a lab, which is most people in Nova Scotia, it’s not always super convenient. You have to arrange a courier, and that’s an additional cost, which can be prohibitive.” Prices for arsenic testing vary widely: a test for arsenic only at the Queen Elizabeth II hospital in Halifax will cost you under $30. In a private lab, however, you can test for arsenic as part of a package deal, and here the price tag’s well over $100.

A poisonous indifference

After receiving their test results, Michelle McGowan and Michael Gunn set about finding a treatment system to filter their water and others’ too. That was easier said than done.

“I had to work way too hard to get the information that I needed about this,” says McGowan. “I spent months, and I mean, research comes very naturally to me, and I spent months and months on this project, so I could get to the bottom of it, so I could find an easy solution that could be implemented for anyone.” They had to look far for expert advice, with most of treatment specialists unable to answer questions about how to handle an arsenic load as great as theirs. There’s also the added issue of finding a system that can remove the two types of inorganic arsenic found in groundwater that’s harmful to humans. The government recommends purchasing systems that are certified by accredited organizations, but not all systems on shelves are.

In the end, McGowan found a system that was up for the task, and by a stroke of luck, one retailer was in Bedford. The other was in California. Their system, quietly working underneath their sink, cost them $800. The canisters on the system are changed once a year, adding another $200, and due to their high load of arsenic, they have an extra arsenic filter. Through it all, she kept acquaintances in the loop on what she found out. “I was sending out everything that I found out to people who told me they were interested. And in the end, out of the 50 people I started with, only three, besides ourselves, bothered to act on it.” The couple was stunned.

“People who had testing comparable to mine who refused to act!” says McGowan. “What I’m most concerned about is people’s indifference. It’s very alarming.” They turned to the government, to let them know of the dangerous apathy around arsenic.

“The day I wrote the premier we pulled up the obituaries. Within two days, three people that Michael knew in this area, that were around his age, had passed away, they all said ‘Please donate to this cancer society…”

The return letter evaporated any hope of swift political action.

“The government’s response was the most ridiculous thing. It was basically a copy-and-paste boilerplate response with trigger words,” McGowan says. “ If I used the word arsenic, I’d get three paragraphs with unrelated information about arsenic. So it was a three-page single-spaced response that did not address anything.” The work being done at the local political level also didn’t sit right with Gunn.

“I felt cheated last year when we didn’t know that there was an issue with uranium and arsenic in our water. And I felt cheated by the county. They should at least tell people to get their water checked,” he says. “Prudence would dictate to me that you should let your constituents know first of all, that they could have issues with their water, and they should get it tested. Just as simple as that. There was not a word of it.”

So he decided to take it into his own hands, and in the last municipal election, Michael Gunn ran for a seat on the Annapolis County Council. His platform came down to two things: safe drinking water, and combatting deforestation. He won by two-thirds of the vote. Meeting his colleagues from around the province proved to him the political silence isn’t intentional, but rather a symptom of the same lack of awareness he himself was a victim of.

caption

A “point-of-use system,” the treatment device McGowan and Gunn purchased, only treats what comes out of one faucet. A bigger, more expensive “point-of-entry” system would treat the water supply for the entire house.“These are municipal councillors from all around the province, and a lot of them are unaware of the arsenic and uranium in the water. And I talked to a lot of them – completely unaware.” Some seemed eager to know more, gladly taking informational fliers he had brought with him, but others weren’t keen. Gunn recounts an exchange with a councillor: “My God, we don’t want that getting out!’ he said, and I ask ‘Well, why the hell not?’ and he goes ‘Well, it might affect my property value!’”

Gunn brought it to the attention of the Department of Environment what he’d experienced in his local community. They made their stance clear: “They all told me, the province is not responsible for what is in people’s wells. That’s the way they looked at it, ” Gunn sighs.

Everything’s online these days

While the provincial government has no regulations in place when it comes to private wells, they do have several information initiatives online meant to inform and warn against arsenic. These include “The Drop on Water,” an information leaflet on arsenic and “Your Well Water,” a series of papers that cover a range of topics related to one’s well. Should one go through these, one would have a clear picture of the risks, and what to do about them. Yet, the online information hasn’t led to people testing more, as the testing habit study showed, and that same study also asked people where they got their information from. Two-thirds couldn’t recall ever receiving any information on well-water testing or treatment, and of the third that could, the most common source of information was private treatment companies, a source interviewees considered the least trustworthy.

The government presence wasn’t always just digital, however. The study on testing habits singled out outreach programs, such as those undertaken by the Clean Annapolis River Project and Bluenose Coastal Action Foundation, as effective. These programs had steady funding through the provincial government’s Environmental Home Assessment Program (EHAP). It would fund information outreach, but would also fund home assessments, where home assessors would come to people’s homes and inspect septic tanks, oil tanks and wells, and discuss water testing and treatment. It ran for eight years and was defunded in 2015. Since then, the Clean Annapolis River Project has continued short term workshops using leftover funds from EHAP, but with those funds gone, the workshops and home assessments will cease. Ask them, they’d love to see a return of EHAP and the home assessments.

caption

McGowan bought the house in Upper Clements in 2002.“It was a very popular program, we always had a wait list,” says Katie McLean. “There’s still a need, both from the drinking water quality and human health perspective, as well as the environmental issues related to that.” Especially the home assessments, test included, were well-received, and when it came to getting people to go for a test, McLean found the test rebate that came with the assessment to be the clincher. “Almost guaranteed. In a lot of cases, it’s the rebate that comes with it that really grabs people’s interest,” she says.

The Department of Environment declined to answer questions about the program’s defunding, but supplied a statement citing budgetary reasons as the cause for the cut.

Lowering the limit, upping the impact

On the 5th floor of the Bethune building in Halifax, Nathalie Saint-Jacques sits with her back to the window in her office, surrounded by research papers that she reaches for and consults as she talks. She has worked to identify the root causes of the higher cancer risks in Nova Scotia, and to what extent arsenic plays a part, focusing on bladder and kidney cancer in particular. The province’s bladder cancer rate is 25 per cent higher than the national average, and for kidney cancer, Nova Scotia’s rate is 35 per cent higher. Both these cancers manifest themselves later in life, usually in people in their 60s. Working for Cancer Care Nova Scotia, Saint-Jacques is now finishing her dissertation, which has looked at the risks of developing bladder cancer after long term exposure to low doses of arsenic, a level more common in the province. While her work is yet to undergo peer review and be published, St. Jacques thinks the numbers are clear – and significant.

“I’m confident there’s an excess risk,” she says. “What I’m not confident about, is that I think it’s much higher than what I’m going to be publishing. I think it’s going to be more like what I detected with my review, where it’s anywhere between a 40 per cent increase to a doubling.”

caption

Graphic by Mikkel FrederiksenAn important factor limiting our ability to measure the cancer risk resulting from being exposed to arsenic contaminated water is what Saint-Jacques calls ‘exposure misclassification’ of the data. To explain, consider the following: Person X lives at location A for most of his or her life, drinking water from an arsenic-contaminated well. Person X moves to location B, drinking water that is no longer contaminated with arsenic. However, long-term exposure to arsenic at location A finally causes cancer to manifest itself and person X is diagnosed. The address at the time of diagnosis is then entered into the Nova Scotia Cancer Registry, the source of Saint-Jacques data. With only this address available, she must assume that the location at time of diagnosis is the same as the place of exposure. When she couples the location of diagnosis with water sampling data from around the province, she can see that person X has cancer but lives in a place where there isn’t a lot of arsenic, and therefore shouldn’t have experienced a lot of exposure. Hence ‘exposure misclassification’.

caption

The Bethune building in Halifax.Not knowing how much contaminated water or food a person ingests over the years also contributes to this misclassification. Such uncertainties lead to biases which, typically, result in an underestimation of the true risk. So when there’s a detectable relationship between arsenic exposure and cancer incidence in spite of this misclassification, in public health terms, you know you’re likely onto something. Saint-Jacques found a link between cancer and exposure levels below the current guideline, going as far down 2 µg/L – a fifth of the current recommended maximum allowable concentration in private well water supplies.

The World Health Organization evaluates the guideline as more information becomes available. Research such as that done by Saint-Jacques’ is put in front of the WHO, and it’s possible we’ll soon see the guideline lowered to 5 µg/L, half of what it is now. When this happens, the number of people living with excessive levels of arsenic will drastically increase.

“If we’re being conservative and are looking at 5 µg/L, I’d say there’s about – and we’re not a big place – but there’d be about 115,000 people that would be at an increased risk, just because they’re drinking water that’s at a level that meets the guideline,” St. Jacques says. Add these numbers to those already in the dark, and can the government stand by its decision to not take a more active part in making sure private well users know the risk?

Causing a ripple

“I think the government has a responsibility here,” says St. Jacques. “I think we’ve done a good job of saying to people ‘Well, if you smoke and you drink and eat this-and-this type of food and don’t do any activity, it’s bad for you. But I don’t think we’ve done a good job with this.” Especially, she says, when the path to reducing the number of people at risk is so straightforward. “This is a problem that’s small in the grand scheme of things, but it’d be easy to address. Even those problems that are easy to address, they’re not being addressed,” St. Jacques concludes.

What options are available? Extending public water supplies, or enforcing testing and treatment on private wells the same way public supplies are monitored and enforced? Easier said than done.

“It’s a political decision, and a discussion for decision-makers in conjunction with what communities necessarily want as well, whether you actually enforce a regulation, and then try to think that through how you would actually enforce it. So it would be very challenging,” says Dr. Trevor Dummer, one of the authors of the study on testing behavior, and a principal investigator on the Atlantic PATH project, a part of a nation-wide cancer study investigating links to lifestyle and environmental exposures.

“I don’t know if that’s actually as effective as trying to improve knowledge and awareness, so that people actually test and treat, because the technology exists for testing and treating,” he says.

caption

Today, Michael Gunn is the councillor for District 8 in Annapolis County. His main focus is on water safety and deforestation.“It’s not just one thing. We need to improve community awareness and community knowledge. We need to improve access to the information that currently exists, and we need to try to reduce the barriers to testing and to treatment within private households,” says Dummer. “People who have their own private well need to understand that it’s their responsibility to ensure the water is as safe as possible.”

Back in Upper Clements, Michelle McGowan and Michael Gunn sees a fight ahead that desperately calls for an ally.

“The apathy, even when people are informed, is…” McGowan lets the disappointment hang in the air. “You combine that with the disinterest from the province, and you just feel screwed.”

“I hope the province lets people know what they’re drinking. Insists on letting people know what they’re drinking,” says Gunn. McGowan carries the thought further. “I think it’s their responsibility, the government. To keep people informed, to make people informed,” she says. “People are waiting on an authority to inform them. Only then will it matter.”

Something’s due

How long will that wait be? At the Nova Scotia House of Assembly, it depends on which side of the aisle you ask.

“I think that we have to take an active part immediately,” says Karla MacFarlane, PC environment critic and MLA for Pictou West. She could see the information find its way by mail, rather than online. “I think there could be a physical presence for sure. There’s all kinds of literature that’s sent out in our mailboxes every year, there’s no reason why we can’t somehow include ‘Have you tested your water this year?’”

Environment Minister Margaret Miller stands firm on the homeowner being responsible for educating and protecting him or herself.

“We expect them to use their due diligence when they’re on a private well,” she says. Awareness of things like arsenic, the Minister says, are part of being a homeowner. “If you have a home, you’re responsible for many things in your home, and you’re not necessarily telling people always to do that, it’s the assumption that they will know.”

caption

Environment Minister Margaret Miller speaking to reporters at Province House in Halifax.The minister feels the government is doing a good job of informing with its online literature, social media, newsletters and public service messages. She personally will tell people to test their water, when the opportunity arises. With what’s offered, it falls back upon the well user to make use of it.

“So they’re not doing their own due diligence as a homeowner, and I guess that’s what the expectation is,” she says, “that people will, if they have their own well, will do their due diligence and make sure to test it.”

Miller says she wasn’t familiar with the research showing a low level of awareness and the limited reach of the online information. Whether the government needs to speak a little louder is something to consider, she says.

“Perhaps we could be putting out more information, perhaps that’s something we should be looking at,” Minister Miller says. “But that’s something for the future.”

About the author

Mikkel Frederiksen

Mikkel is finishing his Master of Journalism at the University of King's College. He's fond of watching films, and sometimes writes about them...

L

Linda Bishop

V

Virginia Schultz

D

David G. Zwicker

K

Kyran McGowan

M

Mary Jewers