From recipes to sharks to antibiotics

Researchers near you are making weird, fun and helpful discoveries

He only turned his head for a second, but that was all it took for the baby shark to wiggle free and bite his finger. For most people, seeing a wild shark would be enough to generate a lasting fear, let alone getting bit by one. But Warren Joyce simply shrugged it off.

“It was just a little knick,” said Joyce, a shark researcher at the Bedford Institute of Oceanography. The Institute sits atop a hill overlooking Halifax Harbour. His bookshelves and desk are decorated with shark memorabilia: Lego sharks, model sharks, artistic photos of sharks.

“There’s something about them as a top predator,” Joyce said. “They’re so graceful and so well adapted to being in the water.”

The goal of Joyce’s research is to help preserve the species. Sharks hold an important place in our fragile ecosystem, and if they were to become extinct, marine life would drastically change.

Although a main portion of Joyce’s research deals with smaller sharks like the mako and porbeagle shark (both having an average length of under 10 feet) he also tracks white sharks, better known as the great white shark.

And yes, there are great white sharks here on the East Coast. Since the early 1800s, 85 have been spotted in Nova Scotian waters. The closest to downtown Halifax was 20 km. away, in Ketch Harbour.

caption

Warren Joyce of BIO has come closer than this to a shark’s teeth.To study the smaller sharks, Joyce and his BIO team usually link up with local longline fishermen. This form of fishing basically consists of dropping a massive long line in the ocean, and then reeling it in. We’re talking 20 to 30 kilometers long—the length of 300 football fields—with more than 1,500 hooks. “Think of it like a big clothesline with hooks hanging off it,” Joyce said.

What they catch is often a surprise. Sometimes they reel in mako or porbeagle sharks that they can measure, then tag and release, to gather data on later.

Great whites are harder to study because they can’t be hauled on board a fishing boat. To tag a great white, Joyce goes out to spots frequented by the species, and tosses in hunks of dead tuna as bait. It’s basically the same as traditional fishing with a single lure and a signal catch, except this catch can measure more than 15 feet long.

The tuna is reeled in until the shark comes within range of the boat, and then a harpoon-like device shoots a tag into the huge fish. This may sound harsh, but Joyce says that when tagging sharks great focus is placed on minimizing harm. Once it’s planted, the great white barely notices the shoe-sized device.

Compiling all the data from tags, researchers gain a better sense of the environments that sharks live in. This can lead to more effective protections. Understanding habitat is the first step in protecting any species.

Joyce is one of hundreds of people in Halifax doing important and unusual research that helps us lead better lives. Our city is a hotbed for research—we have six universities and more than 20 laboratories and research institutes. But few of us know what’s actually being discovered in these institutions. Let’s consider four different researchers, to bring awareness to some of the valuable research often taken for granted.

Historic recipes

When I last had a sore throat my grandma recommended gargling salt water, and it seemed to help, at least temporarily. But if I had been in Halifax in the 1800s, I may have gargled with frogspawn water, the frothy water that you sometimes find at the edge of ponds. It, is essentially, frogs’ eggs. This might seem a little gross, but Dr. Lyn Bennett of Dalhousie University says the concoction was a medical remedy for some of our ancestors.

Bennett is an English professor whose latest project was compiling a list of Nova Scotian medical remedies and recipes—mostly used by British settlers—from the 1730s to the 1820s.

To gather information for the database (see it at https://emmr.lib.unb.ca/), Bennett and Dr. Elizabeth Snook of the University of New Brunswick led a team of researchers that spent hundreds of hours in archives, including the Nova Scotia Archives, searching through microfilm and preserved papers. It might sound dry, but it’s not as boring as you’d think.

“You’re scrolling, scrolling, scrolling and it’s nothing, nothing, nothing. Then all of a sudden… a recipe!” says Bennett. “It’s pretty exciting.”

Some of the wackiest recipes and remedies she has discovered include a cure for a person bit by a mad dog, instructions to carry live fish for a great distance, and a guide to protect your boots from “visitors” (that is, germs and pests).

What’s the most popular recipe, according to people who have listened to her lecture on the database?

“Jello shots,” she says with a laugh. One recipe calls for an alcoholic jelly to be split into small individual servings… aka 18th century jello shots.

caption

Lyn Bennett making mushroom ketchup from a 200-year-old recipe. It turned out, she said, quite well.Bennett admits that the value of her research may not be as easy to recognize as in the traditional sciences, but that doesn’t mean hers has no meaning. Although her work is quirky and fun it still plays an important role.

She highlights the interdisciplinary uses of the database. Dieticians, doctors, sociologists, and economists can all use her information to learn more about what life was like in Nova Scotia hundreds of years ago, and from that come to useful conclusions about today’s society.

As an aside, Bennett mentioned a medieval remedy being used against a modern antibiotic-resistant superbug. In 2015, researchers at the University of Nottingham used a medieval medical remedy for eye infections against the MRSA bacteria. The ancient eye salve was found to be extremely successful.

Who knows? Maybe there’s a cure for other modern diseases to be found lurking in this database of more than 300 medical remedies and 500 total recipes.

If not, there are always the jello shots.

Designing for dignity

What comes to mind when you think of work at the Nova Scotia College of Art and Design University? Maybe perfecting a new sculpting technique, or writing a biography of some French Impressionist? It is, after all, Nova Scotia’s only fine arts university, so you’d think their research would revolve around art.

But one NSCADU faculty member dispels this myth. He doesn’t spend his time in a workshop or gallery but instead at hospitals and seniors’ homes. Industrial design professor Glen Hougan studies the ways elderly people transform their surroundings to make them more livable.

“I’m kind of a weird fit at NSCAD,” says Hougan. He believes most designers aren’t thinking about seniors, which leads to poorly designed products for people with mobility issues.

Older folks around North America have begun altering a range of things to fit their lifestyles. Hougan compiled a record of around 400 of what he likes to call “hacks”—mostly from a research placement he did at the Mayo Clinic in Minnesota.

Innovations Hougan discovered include dog bowls with extended handles so they can be picked up without having to bend over, ice cube trays that double as card holders for bridge games, and a stocking to store bars of soap in the shower.

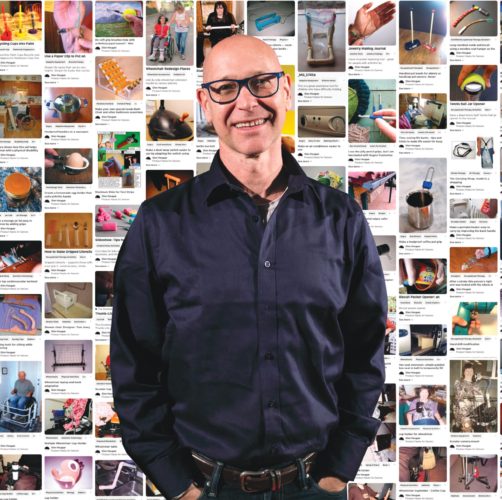

caption

NSCADU professor Glen Hougan has put together a Pinterest page of his research into design for seniors. (https://www.pinterest.ca/seniorsadapt/)He’s concluded that designing for the elderly isn’t just about functionality, but dignity. When you can’t properly shower or eat because the appliances you rely on aren’t designed for you, it’s a dagger to your self-esteem.

According to Hougan, the problem stems from most designers having a narrow focus. “A lot of students just want to design for their own age group. And then when they design for their age group, they’re just designing for themselves.”

He believes there needs to be a paradigm shift, a realization that designing for seniors can be creative and fun. Some people are catching on. He’s already been interviewed by the New York Times and given a TED Talk about his research. Now it’s up to manufacturers to incorporate age-inclusive designs, so that “hacking” will become a thing of the past.

Fighting for a cure

It’s fight night in Halifax, except this fight is for more than glory and a shiny belt. The winner has a chance to save thousands of lives.

This fight isn’t taking place in a local gym, or a packed arena, but, strangely enough, in a small science lab at Saint Mary’s University. Dr. Clarissa Sit, a SMU chemist, sets up “cage matches” between two organisms in an attempt to discover new antibiotics.

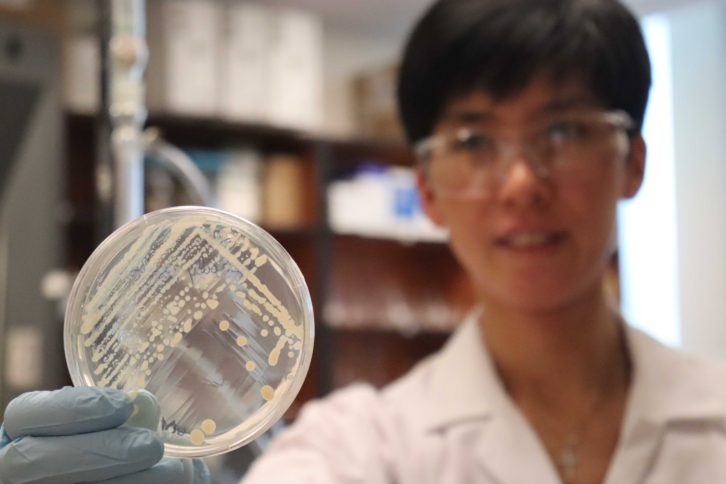

For research that requires nearly a decade in school, and multiple degrees, Sit’s methodology for finding potential antibiotics is fairly straightforward. She puts a sample of a pathogen—either a fungus or bacteria that can infect humans or animals—and another microbe in a petri dish, and has them battle it out until there’s a winner.

If the pathogen is left standing, then the microbe is useless. But if the microbe happens to be victorious, it has the potential to be a useful antibiotic.

Sit says the cage match method is a little more exciting than what usually happens in traditional labs, even though other scientists rarely utilize it. “With this kind of work it’s almost like a pursuit or a chase,” she says. “The adrenaline comes from stumbling on something new.”

Once the cage match has officially begun, Sit’s students periodically check on the results. It can take anywhere from a couple of days to more than three weeks to see any changes, and the excitement is in waiting—not knowing what will conquer what in the battle of organisms.

Sit’s team is currently working on animal diseases. She’s searching for a cure for white nose disease, which has crippled bat populations in North America. Two strains of fungi that successfully fight off the disease in the lab have been discovered, so now they need to test the fungi on the bats themselves.

Ultimately, Sit says, her work is geared towards finding cures to human pathogens. As a graduate student at Harvard, she and a team of researchers used the same cage match method to discover a new anti-fungal medicine.

Her research is vital at a time when the entire world is looking for a cure to a specific disease. Although Sit’s ”fighting” approach has many benefits, it unfortunately can’t be used to find a solution to COVID-19. Viruses don’t respond in the same ways as bacteria and fungi.

caption

Clarissa Sit of Saint Mary’s University first used her cage-match methodology at Harvard.Even if a coronavirus cure is off the table, many important discoveries can be made through cage matching. At a time when antibiotic resistance in humans is on the rise, the winner of Sit’s next fight may go on to change lives.

If Sit’s efforts in finding a cure prove successful, you can be sure you’ll hear about it in the media. But singling out one type of research as successful is problematic because it leaves unheralded a boatload of other important work.

If it hasn’t made waves on Twitter, or been published on the front page of the Times, research often goes unappreciated. This is an unfortunate aspect of being a researcher: you may devote your whole professional life towards work and get zero recognition.

But research doesn’t have to yield immediate results to be valuable. Yes, the current zeitgeist favours technological and scientific discoveries over the social sciences, but researchers of all kinds play a positive role. Research helps.

And at a time when the world is facing turmoil and uncertainty, researchers are more important than ever.

About the author

Simon Miller

Simon is a journalism student in the one-year program at the University of King's College. He covers federal politics, local sports, and everything...