Giving voice to resilience

caption

For nearly 50 years, Indigenous filmmakers in Canada have been sharing their stories on screens across the country and globe.Indigenous documentary filmmakers focus on unheard perspectives

Alanis Obomsawin’s filmmaking career began with a swimming pool.

In 1966, the Abenaki artist was fighting for a place on her reserve for children to swim. The St. Francis River near Quebec’s Odanak reserve was polluted, and Indigenous children weren’t allowed to use the neighbouring white community’s pool.

Obomsawin arranged and sang at fundraising concerts, her voice leading the cause for change. Her activism helped raise the money needed to build a pool on the reserve.

Her voice also caught the attention of the National Film Board of Canada. Though singing was Obomsawin’s storytelling art, film would become her new instrument for change. The NFB invited her to make documentaries about Indigenous culture and issues.

In the 50 years since, she’s made more than 40 documentaries.

Obomsawin’s last name means “pathfinder” — and it’s fitting. Now 84, Obomsawin has carved a path for Indigenous women to pursue documentary filmmaking.

In many Indigenous cultures, women are keepers of knowledge for future generations. They are storytellers in a culture where storytelling is an oral tradition.

Change is a natural part of that tradition; stories, and the way their narrators tell them, transform with time. For many, the movement from oral storytelling to storytelling through film comes naturally.

‘Giving voice’

Catherine Martin considers her documentary work “completely connected to the tradition of oral storytelling.”

Martin, a member of Millbrook First Nation near Truro, Nova Scotia, became the first Mi’kmaq filmmaker 30 years ago.

caption

Catherine Martin’s films include Kwa’nu’te: Mi’kmaq and Maliseet Artists, Minqon Minqon: Wosqotmn Elsonwagon (Shirley Bear: Reclaiming the Balance of Power) and Mi’kmaq Family/Migmaoei Otjiosog.

Martin’s work shares the perspectives of people in her community who haven’t been widely heard — and the perspectives of those who can no longer speak.

Her best-known film, The Spirit of Annie Mae, tells the story of a prominent Mi’kmaq activist who was murdered in South Dakota in 1975. “I knew that I wanted to find the voice for Annie Mae Pictou Aquash,” Martin said. “I knew that she had something to say.”

She spent 12 years researching the film, which was released in 2002. She collected stories from Aquash’s family and community members, including her sisters and two daughters.

When Martin began filmmaking 30 years ago, stories on Indigenous subjects were rarely presented by mainstream media. When they were reported, Martin says, they generally didn’t include Indigenous people’s perspectives and “were sensationalized and negative.”

A study of 30,000 newspaper articles about Indigenous issues shows this is often still the case. The stories appeared in major Canadian newspapers from 2006-2015 and were examined by researchers at York University. The report was published online in April 2016.

The researchers, Daniel Drache and Fred Fletcher, are members of York’s Canadian studies and communications departments. They found that in nearly half of the articles, Indigenous voices were lacking. When voices were missing, stereotypes often took their place.

Fifty years after her fight for the swimming pool, Alanis Obomsawin is still giving voice to Indigenous children’s stories. She says the safeguarding of children “is so important to us and very dear to me.”

Her latest documentary, We Can’t Make the Same Mistake Twice, was released by the NFB this year. The film follows a human rights complaint over the Canadian government’s discriminatory under-funding of First Nations’ children on reserves across the country.

The York study revealed that most mainstream news coverage doesn’t trace many Indigenous issues back to their root cause: a history of racism and colonialism in Canada.

Obomsawin’s documentary explicitly relates the under-funding to those roots. The title, We Can’t Make the Same Mistake Twice, refers to Canada’s traumatic legacy of residential schools.

The documentary features Cindy Blackstock, who filed the human rights complaint, through all the stages of a federal court case. Obomsawin was there when Blackstock won the case in January 2016. Obomsawin had been gathering footage for six years — her longest project to date.

The ‘searchlight effect’

Mainstream media treatment of Indigenous issues in Canada fluctuates between periods of intense interest and indifference, the York study also shows. Media interest is sparked by events such as crises, protests or changes in policy.

The researchers leading the study say the inconsistent reporting is like a “searchlight that is turned on for several days at a time and then darkness descends”.

Obomsawin noticed the media searchlight flickering while she was filming. Mainstream media’s handling of the case, she says, was “on and off.” Major networks showed up for the final announcement, but the Aboriginal People’s Television Network (APTN) was the only network consistently filming alongside her in the courtroom.

Her film is complete and being screened at film festivals, Obomsawin is already eyeing her next project. She’s keeping an eye on the federal government to make sure Indigenous children receive the equal treatment they’ve now been promised.

“Now it’s about what’s going to happen now that we have won,” she said. “The next film I make will be about that. We’ll see what the government does and if all those things are really going to change.

“I’m going to be watching.”

Elle-Máijá Tailfeathers has also seen the thin gleam of the searchlight effect.

Tailfeathers is a member of the Kainai First Nation, or Blood Tribe, in southern Alberta. When a fentanyl crisis hit her 12,000-person reserve in the summer of 2014, it took the lives of more than 20 people.

Many major news outlets reported on the crisis, but Tailfeathers says they didn’t stick around for long. She believes an important part of the story developed after most news outlets left.

The documentary she’s directing will highlight her community’s response to the crisis. After the deaths, community leaders made overdose kits available in homes and public spaces. They created private hotlines to help addicts and report trafficking. They held community meetings. “We did a lot of really innovative things — incredible, groundbreaking things.”

The healing work being done is especially close to Tailfeathers’ heart. Her mom is the head physician on the reserve.

“I want to be able show the kind of work that she and so many other people are doing back home,” she said. “I want to show the strength and resilience and resourcefulness of our people.”

A history

These Are My People, the first documentary by an all-Indigenous film crew in Canada, was produced in 1969. Before that, non-Indigenous filmmakers were occasionally telling Indigenous stories — and often got them wrong.

That was the case with the NFB’s 1958 documentary The Living Stone. The film documents Inuit art. It was nominated for an Academy Award, but gave a false representation of Inuit culture. Scenes were shot in fake igloos, Inuktitut names were mispronounced and traditional tattoos were poorly forged.

“Indigenous expression through the media arts,” says filmmaker Ariel Smith, “is very much linked to self-determination — telling our own stories on our own terms and owning our own content.”

Smith is executive director of the ImagineNATIVE Film + Media Arts Festival in Toronto. For 17 years, the festival has been screening Indigenous film from around the world.

This year, 51% of the films in ImagineNATIVE’s lineup are directed by Indigenous women; by comparison, the lineup at the 2016 HotDocs documentary festival in Toronto had 40% female directors.

“Although 51% is a dream goal for the majority of other festivals, for us it’s actually a lower year. In the past it’s been as high as 70%,” Smith said. “There are very strong female voices.”

Dr. Wendy Pearson knows this as well as almost anyone. She researches Indigenous film and media at the University of Western Ontario. Pearson also guided the production of the World Indigenous Cinema Catalogue, a database of global Indigenous film, for ImagineNATIVE.

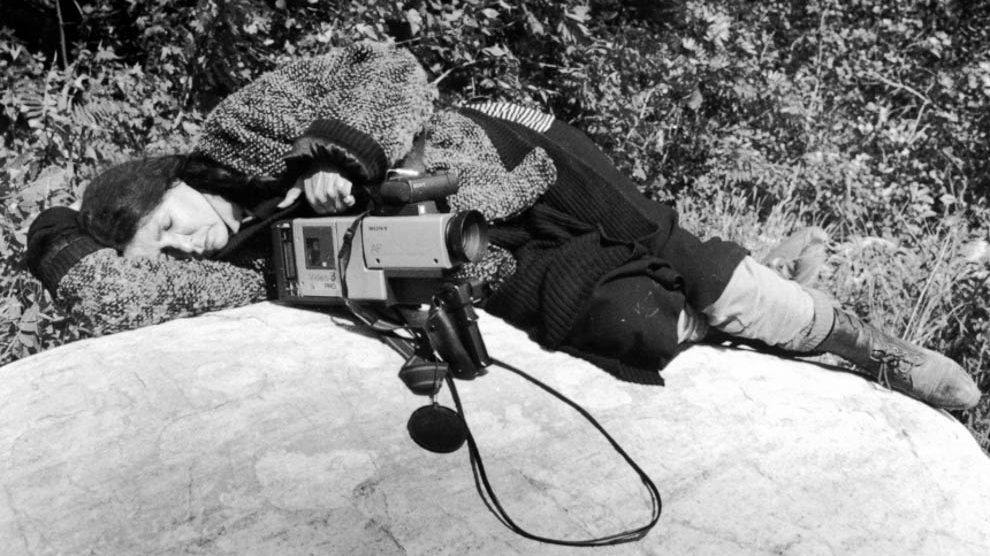

caption

Alanis Obomsawin directs award-winning documentaries about Indigenous issues.

Pearson says Obomsawin is not only a pioneer of Indigenous women’s involvement in film, but an icon. Her body of work is outstanding by any standard. Obomsawin “has made more documentaries than any Indigenous person on this planet. It’s bound to have an influence.”

Pearson also thinks there are structural factors at play.

“Canada has a particularly strong Indigenous film industry,” she said, “partly because it has had some institutional support that other countries haven’t necessarily had.”

Catherine Martin helped found some of those institutions, including the NFB’s Indigenous studio Studio One and APTN. She says they were necessary “so we didn’t have to compete with the mainstream, and hope that a panel of non-native people would see anything important about our art or our work.”

Studio One no longer exists due to cuts in government funding, but the NFB continues to fund Indigenous work on a film-to-film basis. Other institutional programs have emerged to support a new generation of Indigenous filmmakers.

Martin has advice for those filmmakers — or anyone — sharing an Indigenous story: stay true to the values of oral storytelling.

“Tell it well,” she says. “Tell it after you’ve heard it over and over again. Tell it from sources that are first-person or descendants from our people. Tell it from our voices.”