Halifax group advocates for Hong Kong despite risk

Halifax-Hong Kong Link is raising awareness of Chinese extradition practices, other issues

caption

Members of Halifax-Hong Kong Link pose in front of Pier 21, a Canadian symbol of refugeTwo Hong Kong natives in Halifax are raising human-rights concerns around China, even though it means they may never be able to go home.

Joshua Wong and his co-founder Julie first started the group Halifax-Hong Kong Link in the summer of 2019 in response to the proposed extradition bill that would give China the power to extradite person’s living in Hong Kong.

Julie chose not to give her name for safety reasons.

The two have organized rallies for human rights in conjunction with Black Lives Matter, advocated against the Uighur concentration camps in China, and have set up posters and passed out leaflets to educate the public in Halifax.

Now they are targeting the security law that came into force this past summer in Hong Kong.

“It does the same thing but worse,” said Wong when comparing this law to 2019’s failed extradition bill.

Hong Kong operates its government largely autonomously from China under the “one country, two systems” principle.

However now, under the security law, China can extradite citizens from Hong Kong with no due process.

“You have no right to a fair trial…no right to innocence until proven guilty,” said Wong.

Julie said the law allows China to extradite citizens for illegal activity but notes that due to the expansive and vague language in the law surrounding the concept of subversion, China can choose to extradite for simply speaking out against the government.

“Me and Josh are already violating it,” said Julie.

In the past year alone, Wong said 12 protestors attempted to flee Hong Kong but were held without due process and extradited to China.

caption

Margaret McCuaig-Johnston is a lecturer at the University of OttawaMargaret McCuaig-Johnston is a senior fellow in the Institute for Science, Society and Policy at the University of Ottawa where she lectures on Chinese policy.

“Whatever you do in another country can come back to your family where you came from,” she said in an interview.

McCuaig-Johnston said that no one in Canada, or any Western country, is at risk for extradition because all agreements with Hong Kong were terminated upon the security law’s passing in June 2020.

Still, a risk remains.

It is common for people from Hong Kong living abroad to organize and speak out against what is happening back home and sometimes this leads to them being contacted by Chinese authorities, McCuaig-Johnston said.

She knows of a situation where someone was told that if their criticism did not stop, their family back in Hong Kong would be detained.

Travelling abroad also poses a risk, since if someone who is critical of the Chinese government travels to a country with either an extradition agreement with Hong Kong or China, they can be arrested and detained.

But McCuaig-Johnston said the risk does not mean this type of advocacy is bad.

“The more Western attention that is given, the less likely they will be disappeared into the bowels of the Chinese detention system,” she said.

Never going home

Wong and Julie are not planning to go back to Hong Kong any time soon, and both have family and friends there they may never see again.

“If the pandemic is hard enough for someone not seeing their grandparents I’m not sure how you cannot see your family for the rest of your life,” said Wong.

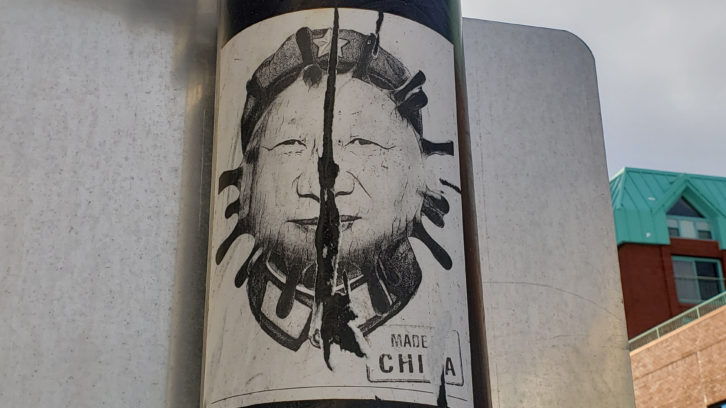

caption

Posters in the South End of Halifax show support for Hong Kong and anti-Chinese government sentimentsStill, the work they do is necessary notes McCuaig-Johnston.

The more Western attention the issues get, the less able the Chinese government is to crack down on dissent, and the more likely China will face global repercussions.

Wong said that Nova Scotians can help their cause in a number of ways, including writing to their members of parliament, questioning the ways in which the Nova Scotia government is relying on China, and advocating for human rights in Hong Kong.

About the author

Nathan Horne

Nathan Horne is a journalist interested in breaking stories that highlight the inequalities and injustices in society.