Halifax’s growing skyline poses threat to birds

Municipality, conservation groups work to address problem of bird strikes

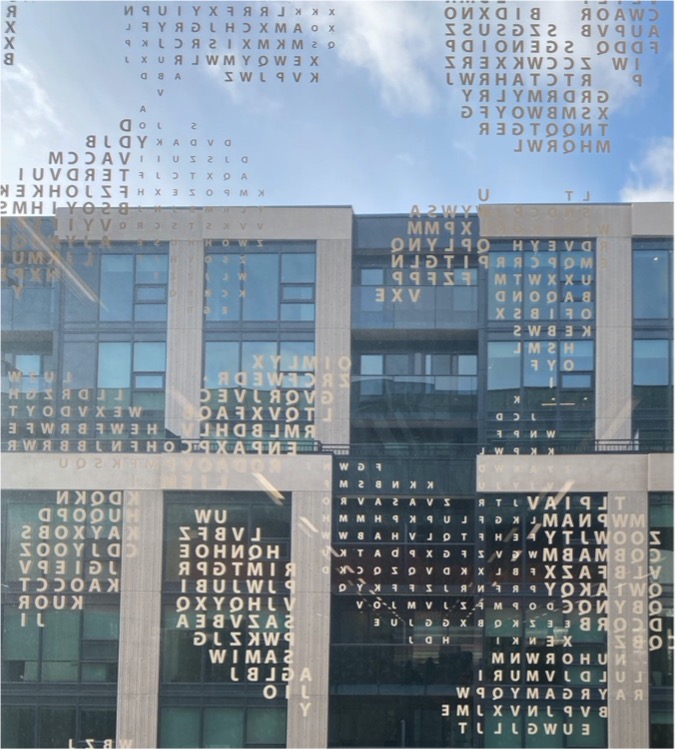

caption

Glass high-rises, like this building at Halifax's Nova Centre, are a danger for birds if not designed with protective measures.Local efforts to protect birds from window strikes are encouraging, said Nature Nova Scotia conservationist Jess Lewis.

But challenges created by urbanization — such as habitat loss and other risk — could undermine these efforts if not addressed.

Community efforts lead the way

Last year, for the first time, Lewis, the conservation programs co-ordinator for Nature Nova Scotia, and her team distributed 250 free window strike kits, which included feather-friendly tape. The kits were made available at libraries, community events, and market booths across Halifax.

Lewis is also encouraged by a 2024 motion approved by Halifax Regional Municipality’s environmental and sustainability committee to explore bird-friendly building designs. The motion directs staff to prepare a report assessing both mandatory and voluntary measures to make buildings safer for birds.

She said this is a step forward.

“This will bring more awareness to the community, building managers, architects, and even landscapers,” she said.

Environment and Climate Change Canada estimate glass collisions kill 16 to 42 million birds annually. Halifax’s efforts have already included initiatives such as Operation Window Strike to reduce bird collisions, the 2024 adoption of bird-safe design guidelines, and community education about protecting their habitats.

Urban growth brings risk for birds

Andrew Horn, a biology professor at Dalhousie University, is sounding the alarm on how Halifax’s rapid growth could affect local bird populations.

“One big thing is that buildings are going up fast in Halifax,” said Horn. “Collisions with buildings can be, and are a big problem, so it’s important that these buildings are built in a kind of bird-friendly way.”

Horn spent his career studying and protecting birds, with a background in animal behaviour and bird research at Cornell University and the University of Toronto. His work includes studying bird communications, assessing environmental impacts, and creating conservation plans for at-risk species across Canada.

He says many birds, particularly songbirds, migrate at night, and light pollution can easily disorient them – especially on foggy nights. The result can be fatal collisions with glass windows.

“It’s important to monitor this,” said Horn, “but it’s also about designing buildings where the issue doesn’t come up in the first place.”

Horn points to the letters displayed on the windows of Halifax’s Central Library as an example of a design feature that may help reduce bird collisions.

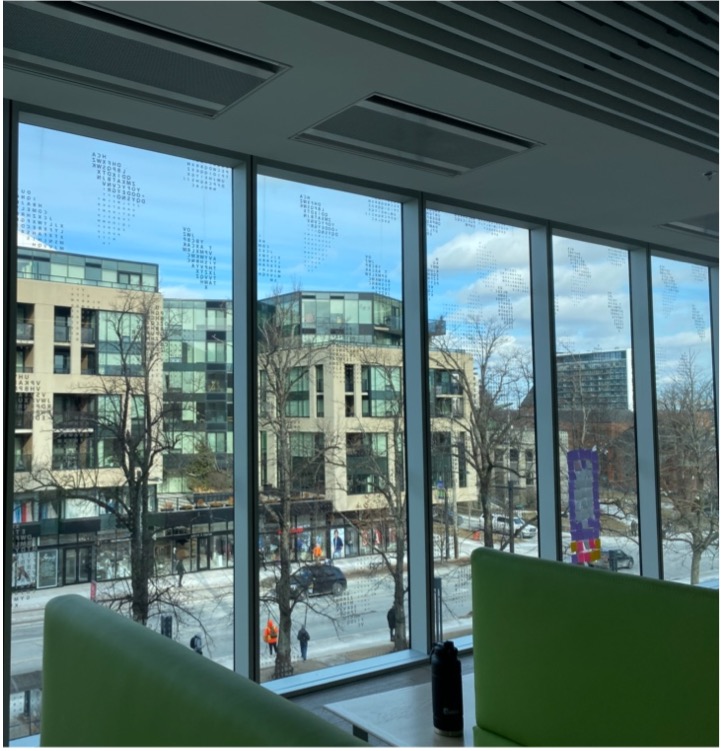

caption

The letters on the windows of Halifax’s Central Library serve as an effective bird deterrent.

caption

Stickers on windows disrupt reflections and transparency, helping birds see the glass as a barrier to avoid collisions.Halifax moves towards bird-friendly status

In 2021, a local panel discussed threats to urban birds, such as window strikes, domestic cats, and habitat loss. This led to the formation of the Bird Friendly Halifax coalition, which helped Halifax achieve entry-level bird friendly city status through Nature Canada in 2022.

“Nature Canada is one of the oldest national conservation charities in Canada, founded in 1939 with the mission to protect, defend, and restore nature,” said Autumn Jordan, Nature Canada’s urban nature organizer.

The Bird Friendly City program is a free action plan for municipalities of all shapes and sizes to base their urban planning and community engagement on best practices in bird conservation science.

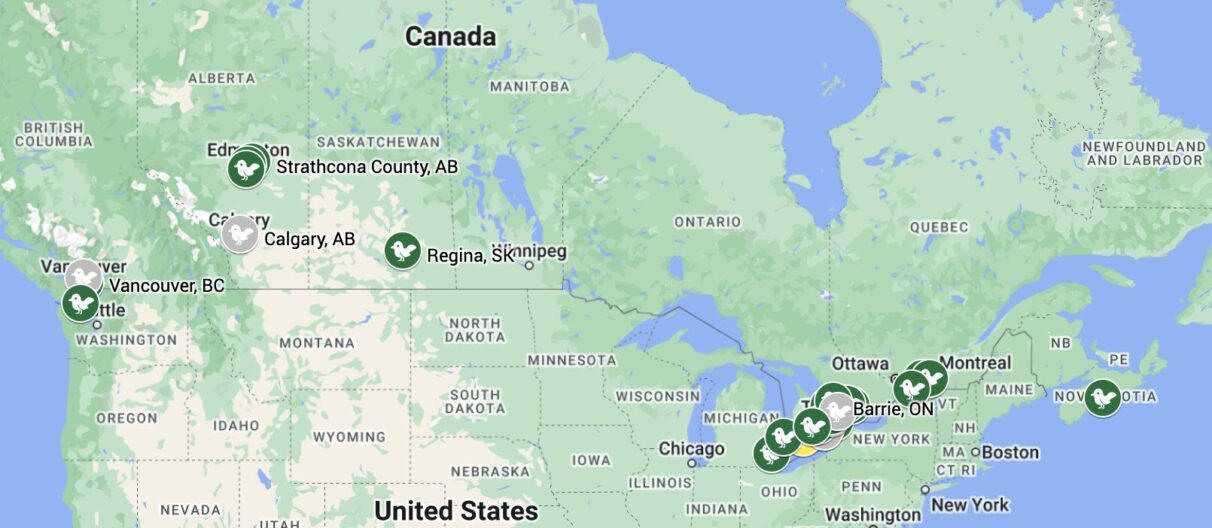

caption

Across Canada, 30 cities are certified as bird-friendly by Nature Canada.Jordan says that Canadian municipalities are located on key migratory routes, making it important to protect our birds as urbanization expands.

According to the 2024 state of Canada’s birds report, produced by Birds Canada and Environment Canada, bird populations have been in steep decline since 1970, including the common nighthawk, named by Bird Friendly Halifax as its bird of the year in 2024.

Its population has dropped to two-thirds below 1970 levels. According to Birds Canada, significant declines across the Maritimes only began in the early 1990s.

“It’s really important that we take action together, holistically, to prevent these declines from furthering,” said Jordan.

Ongoing challenges remain

Halifax scored a 51 per cent on Nature Canada’s bird friendly city certification in 2022, and Lewis hopes to see that rise to at least 60 per cent by the end of 2025. She identified two major obstacles: free-roaming cats and artificial lighting.

“There’s a big issue with cats because we don’t know how to handle the situation,” said Lewis. She notes that while people love their cats and want them to roam outside, this poses a significant risk to our birds.

Halifax has no bylaw on free-roaming cats, making it difficult to manage the issue.

caption

Street lights, like this one along South Park street, pose a risk to birds.The coalition is also working on a lighting strategy for parks and recreational spaces. Members are advocating for directional lighting and motion-activated systems to reduce bird fatalities caused by disorientation and collisions.

“We need to have directional lighting and lighting on timers for wildlife,” said Lewis.

Small steps, big impact

Jordan mentioned that simple, cost-effective measures like installing collision markers on glass, shielding street lamps, and regulating outdoor pets can help bird conservation.

“Birds play a big role in our environment,” said Jordan, “their protection is important to biodiversity and can inspire broader environmental action.”

Currently, only two Canadian cities – London, Ont., and Saint-Anne-de-Bellevue, Que. – have achieved a high-level bird friendly city certification. Both cities have included the Canadian Standards Association’s bird-safe design guidelines into their urban planning and have adopted measures to manage outdoor cat populations and leash laws.

About the author

Ella Karan

Ella Karan is in the fourth year of the King's BJH program. Originally from South Africa, she enjoys photography and writing about culture, conservation...