How a foreclosure unfolds

caption

Nova Scotia's foreclosure system has its roots in the 18th century. Here's how it works.

Understanding why Nova Scotia’s system is the way it is today requires looking back to the very dawn of the colonial era in the province, when it inherited its legal system from practices common in England and Ireland.

Mortgages are, of course, contracts between lenders and borrowers and by the time Nova Scotia came to be, the courts had established that lenders could not simply seize a borrower’s property; the borrower had to be given an opportunity to redeem the mortgage, that is pay back the debt and receive clear title to a property.

Not all law is contained in statutes passed by the elected legislature. There is also the common law, which is law made by judges, and the law of equity, which broadly deals with matters that aren’t addressed by the first two, notably questions of fairness. Administration of the common law and law of equity were long ago merged so are dealt with by the same courts.

The right to redeem a mortgage comes from the law of equity, and the right to pay the lender and thus have title to the property is formally called the equity of redemption. This is where the term equity comes from, in the context of a mortgage, that is, the difference between what the borrower still owes the lender, and the market value of the property.

“The courts of equity invented the right to redeem,” said Justice Gerald Moir, a Nova Scotia Supreme Court judge who heads the court’s foreclosure committee.

“Well, then they had to invent something else so people could enforce security, and that’s when they invented foreclosure. So, (a property owner’s) got the right to redeem, but the court can by various methods, put an end to it.”

Other than scattered references, Nova Scotia has not codified in legislation what should occur when someone defaults on their mortgage, so the courts have continued in the role they have always had, with judges’ decisions over the years shaping the way foreclosures are handled in the province, and the detailed procedures laid out in court rules and practice memoranda that guide lawyers actions. These have been adjusted and amended over time, with the most recent major overhaul in 2008 and some amendments since, such as not allowing deficiencies to be claimed against people who have gone bankrupt.

It starts with a letter

Typically, when people get behind in their mortgage, and once the matter is turned over to the lender’s lawyer, the first thing that happens is a demand letter is sent, noting that the mortgage is in arrears. Most mortgages will contain a clause that states that upon default, the entire amount owed to the lender is due immediately, along with interest.

Some cases don’t go beyond that stage as borrowers are able to pay, either by finding the money or selling and using the proceeds.

If the customer doesn’t make arrangements to pay the lender will start an action in the Supreme Court, seeking an order of foreclosure and sale. The debtor, or in the case of a bankrupt debtor, the bankruptcy trustee, is the defendant in the suit

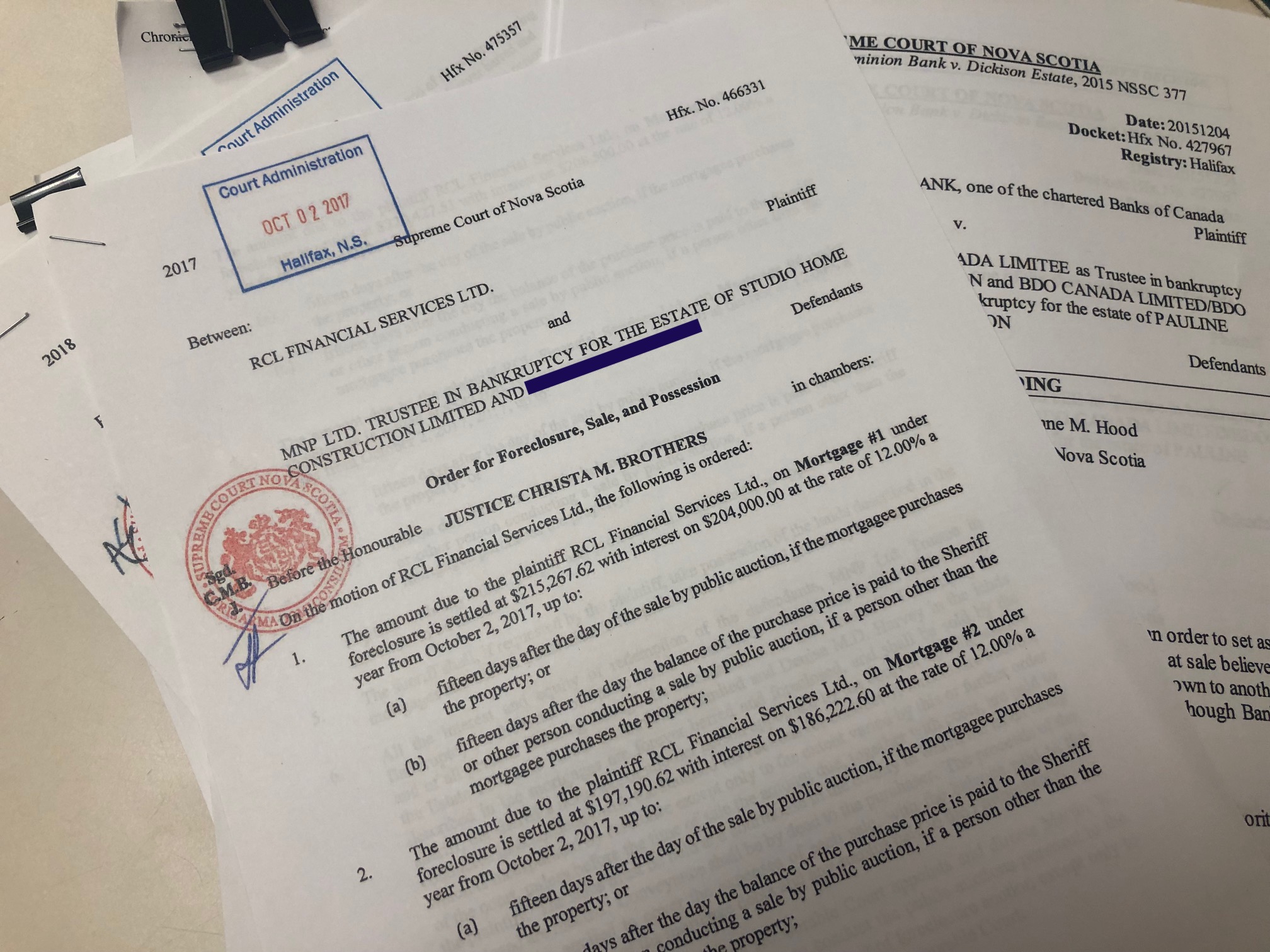

The lender’s action is heard in what is called chambers court, a daily court session that deals with multiple matters. The lender’s lawyer will file evidence to prove the mortgage debt exists, and that there has been a default. This includes an affidavit from the lender attesting to the failure to keep up with payments.

This paperwork is scrutinized by the judge, and if the judge is satisfied, an order for foreclosure, sale and possession will be issued, authorizing an officer of the court to sell the property at a public auction.

From there, anyone with an interest in the property is notified, and the sale is scheduled and advertised twice in a newspaper, often the Chronicle Herald, but also in local papers throughout the province.

caption

Foreclosure auctions for Halifax Regional Municipality are held at the Law Courts on Upper Water Street.“The typical period of time between an order of foreclosure being issued and the day of the auction is normally five to six weeks,” said Nicholas Mott, a lawyer with Cox & Palmer who is prominent among those practicing foreclosure law.

A clause in the Judicature Act allows a property owner to apply to the court to redeem the mortgage by catching up on arrears and the lender’s costs, once in the lifetime of each mortgage, and before the foreclosure order is issued. Mott said in his experience lenders will never say no to someone paying their arrears, right up to the time of a court-ordered auction.

Stephen Kingston agrees, but the veteran foreclosure lawyer said borrowers would do well to talk to their banks early, before the case goes to court, because then it gets expensive.

“Once you start an action and the process begins, costs mount quickly and it becomes very difficult for people to stop the train,” Kingston said. “If you possibly do it, do it up front; communication with the bank is important…and if you can’t afford your mortgage, sell your house.”

The auction sales used to be conducted by Sherriff’s deputies, court officials who do such tasks as transporting prisoners and providing security, but the lawyers in foreclosure practice argued they could run the auctions for a much lower cost. That would benefit the borrower by reducing the amounts that ultimately are charged against them. The court agreed. Now almost all sales are conducted by the same lawyers who act for the lenders, though a lawyer who ever acts for one lender can’t conduct a sale where that institution was the lender.

The auctions are held in the provincial judicial district where the property is located.

Not all advertised actions go ahead. Some are cancelled, often when borrowers are able to pay before the auction happens.

A King’s analysis of sales advertised in 2017 found overall about 88 per cent proceeded to auction. About 30 per cent of advertised sales involved bankruptcies or the estates of deceased individuals. Virtually all of them proceeded to an auction sale. Of the remaining advertised sales, about 84 per cent proceeded to an auction.

After the auction is over and the result confirmed by the court, if the price paid is more than the amount the borrower owes plus legal costs, the auctioneer’s fee and property taxes, the excess is paid to the court. Anyone with an interest in the property, be they other lenders, creditors with judgments registered against the property, or the borrower, is supposed to be notified by the foreclosing lender’s lawyer and can make a motion to the court to have funds distributed to them. The borrower is last in line, so to get any money they have to establish that there are not others entitled to funds before them. With the lender purchasing most of the time, and auctions often not producing any excess, surpluses occur only in a small proportion of foreclosures. In many cases, claims by judgment creditors and other mortgage companies exceed the surplus, and none remains, but in a handful of cases, the surplus.

No representation, no defence

Even though foreclosure actions are lawsuits, they are lawsuits in which the balance of power is hugely imbalanced. Borrowers are typically struggling financially, and are up against experienced lawyers for whom foreclosures are a regular routine. As well, the various court sessions, except for the sale, may be filed dozens or hundreds of kilometres from where the property owner lives. The majority are filed in Halifax, where most foreclosure lawyers and regional bank offices are located.

Technically, the borrower can defend a foreclosure action, but in reality there are few valid defences.

“You would have to defeat one or all of those claims: we lent you money; you promised repayment; you pledged a security, and there’s been a default,” Mott said.

In fact, few borrowers even respond to the notice that is served on them when they are sued by the lender, and if they don’t, the process can proceed without them, what is called ex parte in legal language.

Occasionally, people do try to launch a defence, which often amounts to asking for more time.

One of the things the judges do to try to even out the imbalance is to keep a close eye on all of the evidence and arguments coming from the lenders.

“So when we’re preparing to hear a motion for an order for foreclosure and sale, we’d go through all these materials and we look for things that seem to be unfair even though there’s nobody on the other (borrower’s) side to point it out to us,” Moir said.

He points out the example of lenders charging borrowers high fees for cheques returned by the bank for insufficient funds. “Even if the mortgage allows for that, I don’t, and the lawyers who come to my court now to take those out.” It becomes a question of what is fair, as well as what is strictly authorized by the mortgage.

Moir points out that aside from the right to file a defence, borrowers facing a foreclosure action can also file what is called a “demand of notice,” which will ensure that they are notified of each step in the process. Borrowers do this rarely.

He said in order to protect the viability of lending, security has to be enforceable. At the same time, he said the system has to be able to protect the various interests involved.

“The problem, you know, you don’t want this to become bureaucratic. You don’t want it to be desktop stuff…that can be cheaply done, because there are always interests at stake.”

Moir knows borrowers are vulnerable and the court will decide questions in their favour if it can. That said, fairness can only go so far.

“If you chose to mortgage your house, you’re going to have to live with the deal.”