Immigration

Immigrants face challenges in Nova Scotia: so do their kids

caption

Fadila Chater embraces both cultures, Canadian and Lebanese.Second-generation Canadians make about 7.6 per cent of Nova Scotia’s population

During lunchtime, the aromas of Arabic food, Indian food and Canadian food waft in the cafeteria of Park West School. More than 60 different countries are represented in this school located in Clayton Park West, a suburb of Halifax with a large immigrant population.

“You walk into many of our classrooms and the white kids are in the minority. This is a very diverse community,” said Derek Carter, principal of Park West School, which has students from Primary to Grade 9.

Today second-generation Canadians make up about 7.6 per cent of Nova Scotia’s population and as more immigrants enter Nova Scotia, this number will continue to grow. The immigrant population in Halifax rose to 9.4 per cent in 2016, showing a 2.4 per cent increase as compared to 2011.

A second-generation Canadian is someone born in Canada who has at least one parent born outside Canada.

Maya Makhoul, a second-generation Canadian with Lebanese origins, once heard a disturbing comment from one of her white Grade 3 classmates: “You probably have a bomb in your backpack.”

This was intended as a “joke.”

“They would say that they were scared of me because I was a terrorist and I’d bomb their houses,” said Makhoul.

At the time she didn’t know what the joke meant but when she found out, it was one of the most hurtful things said to her. Makhoul’s mother migrated from Lebanon to Halifax 25 years ago.

“There was this kind of divide between us,” said Makhoul. “The white kids would always ask the people who were ethnically different from them: why is your hair like that? or why is your skin like that? and as a kid you didn’t know, so it was just so confusing.”

Makhoul belongs to one of the many visible minority groups in Nova Scotia.

The changing face of Halifax

There has been an overall increase in the number of visible minorities due to the increased influx of immigrants from non-European countries over the past years. But the experiences of second-generation Nova Scotians suggests the province is on a long road to becoming truly inclusive.

Nova Scotia’s visible minorities make up 6.5 per cent of the population. Across the province, the population identifying as visible minority is concentrated in Halifax, amounting to 11.4 per cent of the city’s population. In Nova Scotia, the largest visible minority groups identify as black, Chinese, Arab and South Asian.

Explore Halifax’s immigrant communities. Darker colours show areas with higher proportions of immigrants. Data is from the 2016 census. Click arrows for legend.

View larger map

Mandeep Kaur Mucina, an assistant professor in the School of Child and Youth Care at the University of Victoria, says racism is an ever-present part of Canada as it is in many other parts of the world where colonialism existed.

Mucina is also a second-generation Canadian and has researched issues relating to second-generation immigrant youth.

“This is a bit of a fallacy, but most people believe that all of Canada is this multicultural, free, loving, engaging society, but this entire nation is built on colonialism and that colonialism has based its entire existence on the slavery of black people and the genocide of Indigenous people,” said Mucina.

In 2014, the Ivany Report on Nova Scotia’s future was released. The report was a call to action for Nova Scotians, which included targets to increase immigration, double tourism revenues and grow more startup businesses.

One of the key strategies highlighted for Nova Scotia was for the province to become more inclusive and welcoming.

The report stated that one of the factors for immigrants leaving Nova Scotia was that the community wasn’t very welcoming.

Born in Halifax, Supriya Arora was taught to follow traditional Indian customs and values. When Arora was in school, she was made fun of for carrying rotis (Indian bread) and dressing in traditional Indian attire, but one incident remains fresh in Arora’s mind.

She was sitting in the front row for an English class. She recalls being the only person of colour in the room.

“This one kid walked in really late and asked the teacher where he should sit, and the teacher asked me to move to the back so that kid could sit in the front. I wasn’t entirely sure why or where that came from,” said Arora.

Arora eventually changed that class because she knew she wasn’t going to excel if that was going to be the pattern.

Reconciling first-generation’s culture and the surrounding culture

Arora faced cultural challenges at home, too. She recalls pleading with her father through teary eyes, telling him: “This isn’t what I want to do.”

Her pleas were in vain. Her father, an immigrant from India, wanted to ensure that his daughter had the best future. For him, that meant she couldn’t follow her childhood dream to become a social worker, but must instead pursue a profession that was more promising in his eyes, such as engineering, accounting or medicine.

caption

Supriya Arora lives in Dartmouth, N.S. and is currently studying at Dalhousie University.Before joining Park West School, Derek Carter was working at Bedford South School. He says during his time there, he noticed that same parental pressure.

“They wanted them to graduate from school and become doctors and lawyers and engineers and things that was their vision for them,” said Carter.

Mehrunnisa Ahmad Ali is a professor at Ryerson University who specializes in immigrant children, youth and families.

“Those that have succeeded in their countries of origin have become socioeconomically affluent because they have gone into fields like engineering, medicine, etc. So, that is the parents’ experience and that’s all they know,” said Ali.

“So, they think the same thing will apply here, but they are imposing that or using that as an example to get their children into these fields.”

Arora grew up in Halifax, but lived in a traditional Indian joint-family, where extended family, typically consisting of two or more generations, live together under the same roof. Arora lives with her nuclear family, her grandparents and cousins.

The reality at home was different from the atmosphere at school for Arora. At school, she learnt how to foster a sense of individuality and create dreams and goals for herself.

“It’s a bit of a balancing act between fulfilling and respecting family expectations and testing my boundaries to find who I am and what I want,” said Arora.

“Indian culture in general, it’s a very like ‘we’ culture. Whereas Canadian culture is more of like a ‘me’ culture.”

The only social events Arora remembers going to is a hockey game, prom and a school dance.

“We were so focused on studying all the time because there was that pressure for academics. I feel like I missed out on like a lot of opportunities,” said Arora.

“I think some of it was self-inflicted too because I just wanted to make my parents so proud.”

A state of crisis

When Arora was in high school, she felt like her identity was in a state of crisis.

“You can get really acquainted with self -doubt in high school because you get to that stage of who am I, where do I fit in kind of thing. On one side you have your Indian culture, but then you kind of want to explore other things,” she said.

“Being a second-generation Canadian, an immigrant child in this society, is hard and there’s a lot to figure out,” said Mucina.

In situations like this, Mucina encourages a little bit of resistance.

“I think that one thing that young people could do better is actually pushing back a little. Especially for young girls, it’s a hard thing to do, because we’re not encouraged to do that,” said Mucina.

“What I’ve noticed has happened is, a lot of the times the young people will either veer so far away from their culture that they don’t see themselves reflected in it anymore and they almost go the other direction and will do everything in their power to be closer to whiteness, or they’ll completely integrate into it.”

When Fadila Chater told her parents she wanted to do journalism, the first question her mom asked was: “Is there any money in that?”

Chater was born in Windsor, N.S., where she and her sister were the only brown students in class. Her parents immigrated from Lebanon.

Like Arora, Chater’s parents were invested in her academic life, but her social life took a backseat.

“When it came to social things like dances, I was never allowed to go to until I was in my high school years. The social aspect of growing up was very much a struggle to understand,” said Chater.

“Whenever my friends would be like, why can’t Fadila hang out with us, why can’t you come over? I’d always have to say my parents are really strict about this stuff. They come from a culture where women really couldn’t leave the house unless it was absolutely necessary and if they did, it would be with their sister or with their cousin, who is also female.”

This led to constant conflicts within the house. Chater’s mom would get really frustrated with her for wanting a social life and Chater would get frustrated with her mom for trying to keep her away from it.

“I always saw my parents as a wall in my social life and my development as a kid in the society that they’re not used to, that they’re not familiar with and I saw my Canadian culture and my Canadian friends and Canadian identity as an escape,” said Chater.

“This is what I should be; this is who I should hang out with, because everyone else is so free to do whatever they want, but I’m not because I’m Lebanese when I go home.”

For Chater, things have changed. Now she is proud of her identity. Her parents have become open and accepting over the years and they have welcomed her white boyfriend into the family.

caption

Natalie Cantle’s father migrated to Halifax from England in 1953.Even white second-generation immigrants feel some sense of difference.

In 1953, Natalie Cantle’s father migrated from the U.K. to Canada. He docked in Quebec and took a train to Halifax.

Cantle says she was free from bullying because she didn’t look very different from most Nova Scotian kids. The only reason her peers would understand she was not entirely from Canada was her uncommon last name.

Cantle belongs to the third-largest ethnic group in Nova Scotia, English, with 28.9 per cent of Nova Scotia’s population claiming some English ancestry.

“I felt excluded sometimes because I had different routines and growing up my dad would teach me to spell in different ways or just different weird foods,” said Cantle.

Similar to Chater and Arora’s experience Cantle’s father was invested in her education from a very young age.

“Pushing that hard made me want to not do as well. I did well anyway but it made me kind of rebel against it,” said Cantle.

The cultural conflict Cantle had with her father was more about good etiquette.

“I started swearing a lot and my dad was like we come from an English family, we don’t swear a lot,” said Cantle.

The changing landscape

As a six-year-old girl in 1971, Rana Zaman packed her bags and left her home Karachi, Pakistan, and took her first plane ride to Nova Scotia.

“This was not a very multicultural, diversified community. We landed in Halifax and at that time it was a completely different landscape,” said Zaman.

Nova Scotia has one of the lowest numbers of immigrants in Canada while Ontario, British Columbia, Quebec and Alberta have the highest number of immigrants.

Zaman moved into her first home on Barrington Street.

Zaman was excited to come to Halifax because she was leaving Pakistan during a time when there was war between India and Pakistan. Zaman’s happiness was short-lived. As soon as she started school, the nightmares began.

“She (another student) punched me in my left ear, and I remember the stinging pain and then blood started coming out,” said Zaman.

“When my mother saw that she was just livid, you know, and she came and said, what is this going on here? In her limited English, she could only show emotion more than anything else.”

This was Rana Zaman’s experience in elementary school. Zaman’s mother didn’t understand the culture or the language.

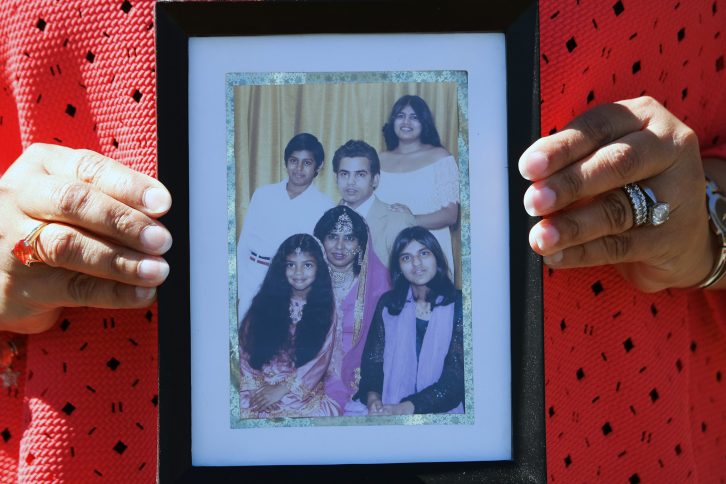

caption

Rana Zaman displays a portrait of her (top right) with her parents and three siblings.“I was not white enough to be white and I wasn’t black enough to be black. The bullying started because I was unusual and combined with things, like my mother would give me a shower in the morning, put oil in my hair, braid them into little pigtails because that’s how it was in Pakistan,” said Zaman.

“When my mother thought she was doing me a favour, it was actually seen as, ew, you’re so dirty, your hair is greasy, don’t you shower?”

At the age of 15, Zaman finally took Taekwondo classes and learned to stand up for herself.

Zaman says the children born now don’t have to face all the struggles that she endured as a child.

“The biggest change is the opportunity and the growth in numbers and diversity. Even the Pakistani kids have the opportunity to have a peer group, which they didn’t have in my time. They didn’t have it in my children’s time, but in this current time, the new generation, they have that support,” said Zaman.

Zaman argues that cultural events are flourishing in Halifax and more and more associations have come into existence.

“Now, you can take pride in your identity,” says Zaman.

As a child, Zaman was often ashamed about her heritage. At times, she wished her mom was more Canadian but as she grew older, she realized how her parents protected her despite their limitations.

As a result of her experiences, Zaman tried to be understanding of the challenges her children faced. When her daughters dealt with depression and anxiety, she sought help. When her children were bullied, she was quick to act.

caption

Rana ZamanAt one point, Zaman invited her daughter’s bullies’ home and they even ate Kraft Dinner because she wanted to show that they were just a normal family.

“I tried to be more free with my children and not be as strict as my parents. I allowed them to have sleepovers here, allowed them to go for parties. Unfortunately, my kids face those pressures for drugs and alcohol and relationships. So, when they went through that, I didn’t. So where do you balance it?” said Zaman.

Mucina, the University of Victoria professor, says immigrant parents’ life circumstances play a role in how they raise their children. She says many researchers have found that the first two years of any person’s life after migrating sees a deterioration in their health.

“Immigrants are usually (the) sort of the people who are scapegoated when things are not going well,” she adds.

She says these experiences that the parents go through leads them to get protective of their children.

“The only way they understand to protect them is to surround their children with what they know is being safe and what do you know as being safe? Everything that you grew up with, everything that you valued,” said Mucina.

“So, if you only encounter unsafety and fear and violence from the outside world, you want to protect your kids by protecting them from the things that you are experiencing.”

Mental health

Mental health is still considered a taboo topic in some regions of the world. When immigrants come from different regions with various traditions, they sometimes find it hard to understand mental health struggles.

“As a kid, I never knew what a panic attack was when I would get them. I thought it was just me and something was wrong with me,” said Maya Makhoul.

Makhoul recent was diagnosed with post-traumatic stress disorder and anxiety and says it was very hard for her because her mother didn’t know what it was, and didn’t believe in it.

Makhoul and her sister had to keep talking to her mother to explain these struggles. Now her mother is very understanding.

According to Fadila Chater, the general attitude around mental health was, “If you’re sad, you get over it. If you’re depressed, you get over it.”

“How exactly am I supposed to tell my parents, who are much older than me, that have different life experiences than I have, that I can’t just stop crying,” said Chater.

Arora says her experience was similar. She says mental health is a struggle that often goes unnoticed.

“Mental health, it’s a really big issue for me personally because there are so many people that suffer in silence. I don’t think that the Indian community is open enough for people to want to open up, even if they are suffering from something,” said Arora.

Arora wishes that she could have a more open and honest conversation with her parents.

“A lot of that’s really hard because a lot of parents I know will shut you down right away and be like no, this isn’t up for discussion or this is just what you’re going to do,” said Arora.

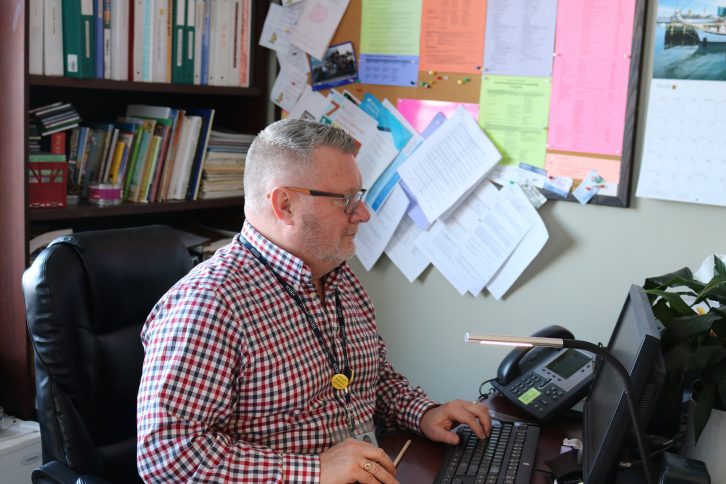

caption

Derek Carter is the principal of Park West School in Clayton Park West.Back at Park West School, the principal says they do their best to help students with mental-health struggles.

“We try to educate the parent and let them know that this is serious. We try to hook them up with different resources at the IWK or community support or community services, whatever might be,” said Derek Carter.

“For the most part, we find them receptive. It’s just that I think it’s a cultural thing. It’s a stigma, it still is here in Canada too, but we’re working to change that.”

Solutions

Chater, Arora, Makhoul and Zaman have all had to answer that most pressing of questions: “Where are you really from?”

To Arora, hearing this repeated question is frustrating.

“I get where the question comes from, because I’m not white, I don’t look like I’m from here. But when they question it and they’re like, no, no, where are you really from? Like, it gets you a little bit because I am from here, I am a Canadian, so I’m just the same as you are,” said Arora.

Lori Wilkinson, professor of sociology at the University of Manitoba, has researched issues pertaining to second-generation Canadians.

“For many people who have that kind of question, I think that they don’t even realize that they’re being hurtful when they ask that question. I don’t even think it dawns on them that, you know, somehow, you’re labelling somebody as not really a Canadian or not as an authentic Canadian, which is how it’s often internalized when you’re asked that question. But I also think that there’s some racist intent around it among some people as well,” said Wilkinson.

Zaman argues that striking the right balance is key to finding the solution.

“There should be some compromising and understanding for the sake of the children, their mental health and their future. You have to help them strike a balance,” said Zaman.

“Despite whether you’re happy about it or not, in the end, it’s their lives. They have to live to the best of their abilities and their situation that allows them to live it.”

She adds: “For the kids, it is important to balance what they want, and they see as the best of each world and to take it forward and be in harmony with their parents, themselves and the country they’re in.”

A

Andrew Barker

M

MIDHUN GEO DAN