Keep uranium ban to ‘protect the health of Nova Scotians,’ say physicians

Groundwater contamination and lung cancer among mining risks, say opponents

caption

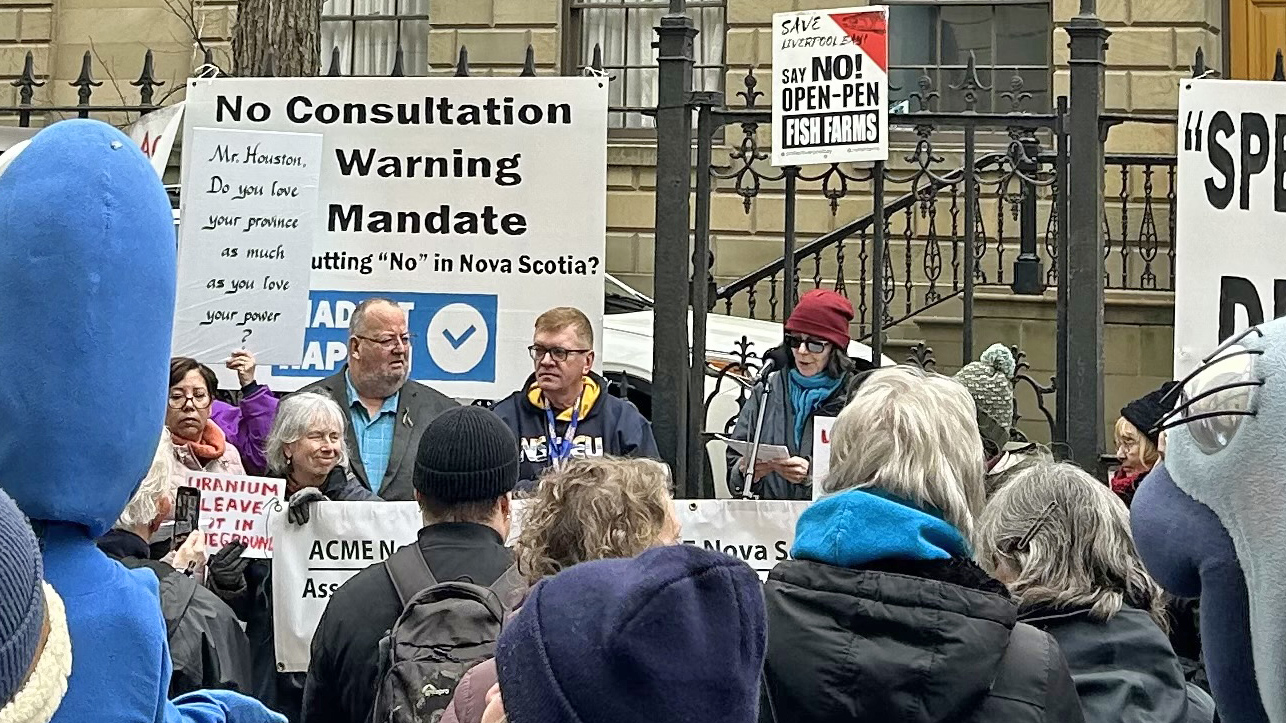

Laurette Geldenhuys, of the Canadian Association of Physicians for the Environment, addresses a rally in Halifax on March 5. Geldenhuys said fracking and uranium mining are dangerous.Nova Scotia Premier Tim Houston’s proposal to repeal bans on uranium mining and exploration has raised concern from physicians and environmentalists alike who fear the health risks associated from uranium mining.

This was one of many concerns voiced at the Special Interests For Democracy rally earlier this month at Province House.

The March 5 rally featured speakers from groups such as the Ecology Action Centre and the Canadian Association of Physicians for the Environment (CAPE). Demonstrators spoke out against an omnibus bill tabled Feb. 18 that would repeal the Uranium Exploration and Mining Prohibition Act — the bill that officially banned uranium mining and exploration in Nova Scotia in 2009.

Rattling tambourines and whooping cheers echoed through the streets around Province House on Hollis Street downtown Halifax, where hundreds of protesters gathered to voice their grievances with the Houston government.

CAPE’s Dr. Laurette Geldenhuys told the crowd that uranium and fracking bans must be upheld to “protect the health of Nova Scotians.”

She said uranium mining can release uranium’s natural decay products into the environment. This includes radon, an inert gas that is the leading cause of lung cancer among non-smokers.

In addition, above ground uranium tailings can be spread by weather, risking infiltration into groundwater and airways, Geldenhuys told The Signal in an interview on March 4.

“It doesn’t just sit in the environment,” said Geldenhuys. “It gets blown around in the dust and it gets all over the place, gets into the water. We breathe it in.”

caption

A pile of signs at an anti-uranium protest at Province House in Halifax on March 5.“And Nova Scotia being such a tiny province and being relatively highly populated per square kilometre, our population would be at far greater risk than, say, a province like Saskatchewan, where most people are living far away from where these activities are occurring.”

Houston cites tariff threats from the U.S. as an incentive to repeal the bans, wanting to “take the ‘No’ out of Nova Scotia” in an effort to make the province more economically self-sufficient by expanding the mining industry.

The largest uranium mine in the world is in Cigar Lake, Sask., and Sean Kirby, the executive director of The Mining Association of Nova Scotia, told The Signal that Nova Scotia should look to Saskatchewan as proof of the safety of uranium mining.

“If uranium mining actually caused the kind of concerns that people sometimes raise about it the people of Saskatchewan would tell us so,” said Kirby. “Because they’ve had uranium mines going back to the 1950s.”

Kirby says the fear around uranium comes from Hollywood storytelling, and that “there was no scientific basis for the ban.”

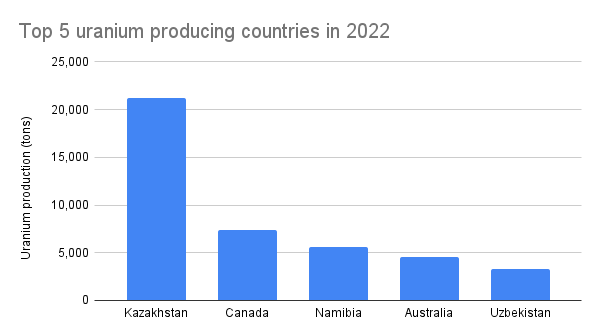

caption

Uranium production in tons by the top 5 uranium producing countries in 2022. (worldpopulationreview.com) Produced on Canva.However. Nancy Covington, a physician who was part of the movement to ban uranium mining and exploration in 2009, argues there is recorded evidence of the risks.

“When uranium mining is done, the particles of dust are blown around,” Covington said in an interview.

“They end up landing on lichens, on all vegetations, but caribou like lichens, and they eat it. And so the particles enter the food chain in this manner, and it has been calculated that there’s significant increase in cancer risks for those who eat caribou in certain northern areas.”

While there is limited data on uranium deposits in Nova Scotia due to the exploration moratorium that has been in place since 1981, geologists argue that Nova Scotia’s bedrock composition would be suitable for uranium deposits. Uranium ore can be found in granite, which comprises 20 to 25 per cent of bedrock in Nova Scotia.