Long-form at home in digital age

caption

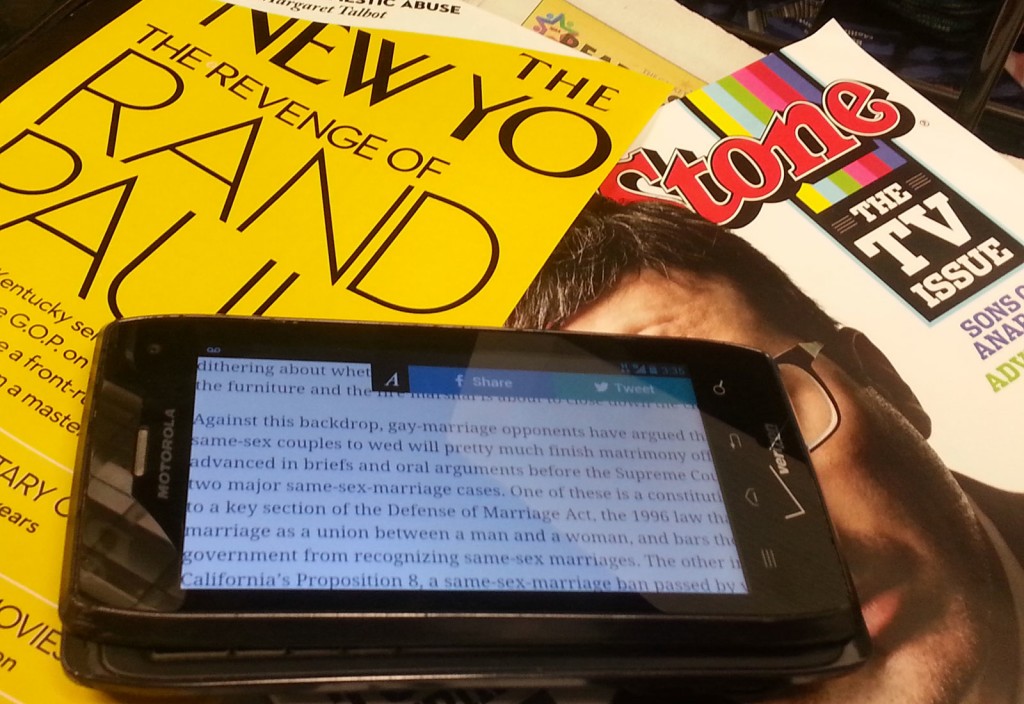

Two types of magazines: the scroll-able smartphone on top of traditional print.Twitter, schmitter. Today’s readers also crave long-form

If long-form journalism has a smell, your best chance of catching a whiff is in Brooklyn. Not that Brooklyn is in need of scent — Nathan’s Famous hotdogs with sauerkraut have covered that for 98 years.

But if you could assign an odour to long-form, Brooklyn would be ripe with its fragrance.

In the Digital Age long-form is in style: a hip brand of journalism spanning everything from awkwardly-emotional memoirs about Joe Schmo’s first time grating carrots into his hummus to deeply cerebral exposés.

Aaron Lammer and Max Linsky are two of the brightest men in the Brooklyn neighbourhood known as Dumbo (“down under the Manhattan Bridge overpass”). There, from a loft, the two pals run their aptly named company, Longform.

caption

No matter the portability of personal devices, print copies have their advantages.Launched by the pair in 2010, Longform compiles narrative articles to its home page, Longform.org. Every day a team of editors sifts through articles to find the three or four Longform will feature that day. Longform doesn’t produce original content; the stories it posts have already been published. Some articles are sent directly to Longform’s editors. Others are discovered on Twitter. Articles are posted each day and stay on the home page for 24 hours.

In 2010 Longform was an innovative idea. BuzzFeed, The Awl and Gawker were up and running, luring audiences with photos, click-bait articles and new multimedia features. Magazines and newspapers were writing long-form, but opportunities to incorporate multimedia are limited in print. Lammer and Linsksy wanted to take the best long-form journalism and display it with help from the latest technologies.

“Often people (ask) ‘oh is this just for, like, journalism nerds who used to work at newspapers in the 90s?’” says Aaron Lammer.

“That couldn’t be further from the truth. It’s (for) a broad spectrum of readers who are reading at a broad spectrum of their free time. And we’ll go out after all of them.”

In September 2014, Longform launched the improved Longform App. Pioneered by Lammer in 2012, the updated app links to publications users choose to follow. Users keep tabs on that title by following individual articles and authors.

“There are all these new outlets that are really publishing long-form features, a lot of them every day,” said Lammer. “That didn’t exist when we started.”

When Longform launched, reading off of a screen was still a novelty. Not anymore. Screens are smaller; smartphones and tablets dominate the market.

“I don’t think that the desktop browser is a very good place to read longer feature articles,” Lammer said. “And I do think that your phone or your iPad is a pretty good place.”

According to a Sept. 26, 2014 article in New York magazine, 70,000 people had downloaded the Longform App.

The app had been available for one week.

Not your father’s long-form journalism

In 2000, a boy in Portland, Ore. became news first in the Northwest and then from coast to coast. The left side of Sam’s face parachuted out from his jaw. The mass settled in his cheek stretched to his ear. Sam had to be careful flossing his teeth: his left eye was dangerously close to his molars. Sam’s story was remarkable. Journalist Tom Hallman told it remarkably. It wasn’t a nice story; it was a moving read. It defined long-form journalism at the start of the century. Now Hallman’s employer, the Oregonian daily newspaper, is fighting to recapture that definition.

Once a Sunday morning coffee table pursuit – with Joan Didion and Tom Wolfe’s fingerprints all over it – long-form has left its home in print to become the Internet’s tenant. Serial, multi-part narratives, investigative reports and front page features all qualify as long-form, and each is now digitalized. Online companies are cast across the web, delivering long-form content to anybody with Internet access.

According to the Canadian Internet Registration Authority’s 2013 data, that’s 87 per cent of Canadian households.

The creation of online start-ups is both a cause and an effect of long-form’s popularity. The growing demand for long-form leads to the advent of more and more forums for stories. In turn the success of websites leads to a steady rise in the amount of available long-form.

For newspapers and magazines, the popularity of online forums and the stories they host is a mixed blessing. Print media continue to supply much of the long-form content that websites feature. At the same time, economic constraints are forcing print publications to cut resources devoted to long-form coverage.

While long-form writers rush to squeeze through a side door, the main gate stays barricaded.

No problem for people like Aaron Lammer. As technology has advanced, so have opportunities for the tech-savvy and entrepreneurial.

Changing the status quo

At the Oregonian in Portland, Ore., editor and writing coach Anna Griffin says long-form’s popularity hasn’t immunized the newsroom from budget cuts and a lack of advertising revenue. According to Ken Doctor’s 2010 book Newsonomics, staffs at newsrooms at U.S. daily papers are 20 per cent smaller than in 2001. The $49 billion that dailies generated in advertisement revenue in 2000 was down to $28 billion by the end of the decade.

Tom Hallman’s 2001 Pulitzer Prize for Feature Writing, won for his four-part story The Boy Behind the Mask about Sam Lightner, highlights the Oregonian’s tradition of hard-hitting long-form. At the start of the century, the Oregonian regularly ran serial narratives. For a newspaper regarded as one of the best in North America for long-form coverage, today’s challenge is defining modern long-form journalism.

“I think we’re still trying to figure out – in the newspaper industry – what long-form actually means these days,” says Griffin. “Is it 3,000 words all in one chunk? Is it 15,000 words told in six parts? Is it just a really long feature story?”

The answer isn’t to dismiss long-form. The paper does it well and Portlanders are accustomed to seeing long-form in the paper. But long stories take time. Staff and budget cuts make it difficult for the Oregonian to devote the time and money to long-form it could in 2000.

In Tampa, Florida, more than 4,000 km southeast of Portland, where the Northwest’s pines give way to orange groves, the Tampa Bay Times (St. Petersburg Times until 2012) is another paper with a rich long-form history.

According to Times editor and vice-president Neil Brown, it’s also a paper whose writers are now forced to adjust to how the newspaper writes long-form.

Brown says new tools and technologies can increase stories’ lifespan. Stories can live for longer than one day when infused with video and graphics. They can also travel farther. When websites pick up a newspaper’s work, they spread it to an audience that is wider-reaching than the newspaper’s target audience. Even when an article appears on only one website, social media makes the article available to the masses with one click. For articles to stick out, they have to be more than well written. Many times, the writer needs to promote the work.

“Because it’s now so fully a digital age,” says Brown, “we know when we’re writing (a story) that it’s reachable beyond Tampa Bay.”

Broadsheets to booklets

Cosmo Garvin, a freelancer and contributing editor at the Sacramento News & Review, an alternative weekly newspaper, says daily newspapers face another challenge in writing long-form. Garvin believes long-form isn’t always engrained in dailies like it is in alt-weeklies. Especially in cities dominated by one daily, alt-weeklies need a distinguishable identity to attract readers. There are opportunities for secondary outlets to brand themselves with consistent long-form.

caption

Tablets, smartphones and e-readers deliver a quick jolt of long-form any time, anywhere. Here, a bus rider reads from his smartphone.“(Long-form) is just kind of in the DNA of the alt-weekly format,” says Garvin. “Until they stop printing I think that’s still going to be (part of the alt-weekly format.)”

The Virginian-Pilot is a daily attempting to buck that trend. Norfolk, Va.’s daily newspaper employs an inventive, off-line strategy to keep long-form in its DNA. Every summer the paper runs a “summer series.” The series is made up of at least one multi-part narrative, typically about a local issue or the region’s history. The 2014 summer series featured two long-form narratives, both told in multiple parts.

“It did not run online at all,” says Diane Tennant, a reporter for Evening Pilot, the paper’s digital magazine.

This was a financial decision.

“These summer series are a big investment of time. They cost money,” said Tennant. “The Pilot was not willing to give it away. So it runs in print.”

After a series runs, the Pilot reprints each story into booklets – which often include bonus content – and makes the booklets available for purchase. In June 2014, the Pilot ran The Lucky Few, a seven-part series about local soldiers who fought in the Second World War returning to Normandy. Escape, a five-part series about the Norfolk area’s ties to the Underground Railroad, ran in August.

For love of long-form

Like alt-weeklies, many magazines brand themselves with long-form.

According to Cape Breton native and Edmonton-based author Lynn Coady, magazines like the New Yorker do it best.

“I remember spending a whole summer in my early twenties house sitting for a couple of poets. They had stacks and stacks and stacks and stacks of the New Yorker in their basement,” Coady says.

“I spent an entire summer just reading the New Yorker. I think that’s what really inculcated a love of long-form journalism in me.” (Coady’s backdrop that summer, the grey waves of the Pacific in Victoria, B.C., may have helped too.)

Coady describes the summer as “a wonderful crash course in quality long-form narrative.” More than a decade later, she met author Curtis Gillespie while the two were teaching in Banff. Lamenting the lack of quality long-form platforms in Canada, they hatched a plan to create a magazine devoted to the rich, meaty long-form stories deficient in Canadians’ literary diets. They called it 18 Bridges and launched it in 2005 in print and online.

But magazines face challenges: start-up magazines sometimes aren’t large enough to have circulation departments.

Then there are economics.

“A lot of the magazines that are doing (long-form) work in Canada are the non-profits,” says Patricia Elliott, an assistant professor of journalism at the University of Regina.

“What concerns me, if we’re looking at trends for long-form, is most of the action (in Canada) is in that non-profit sector. These are the magazines that have really had the bottom fall out on federal support.”

When massive government cutbacks began 20 years ago, Elliott said, the Canadian postal subsidy on magazines applied to 8,000 titles. In 1996 the postal subsidy for a 300-gram magazine was knocked down from 37 cents to 13 cents.

In 2013, Elliott said, the subsidy covered 821 titles: about one in every 10 magazines it used to anchor.

Long-form for long-form’s sake

Aaron Lammer’s interest in long-form has always been technological. In 2010, more people were staring into computer monitors than were nose deep in paperbacks. Now more people read on hand-held devices than on desktop computers.

“We look at what we’re doing as a utility,” said Lammer. “We’re there to fill a specific role for the people who read. And thankfully there are a lot of them.”

Lammer is on top of long-form journalism. Technology is advancing and, because of it, so is his company. People love reading and people love being up to date.

But why the love of long-form?

Newsroom veterans, including Anna Griffin at the Oregonian, are wary. Griffin says long stories aren’t better than short stories because they’re long.

“I think there is a cult of long-form that doesn’t always jive with how people use the media these days,” Griffin said. “The thing that we’re trying to balance is not every story needs to be 5,000 words.”

Creation of online media websites

Editor's Note

This story was reported and written by Oct. 17, 2014.