Not all journalists in style

caption

A model at FashionEasta, a runway show and sale in Halifax on September 28, 2014.A mess of loose fabric, tangled thread, paper patterns and colourful sketches. As the sewing machine whirrs, scissors glide through fabric, and steam wheezes from the iron, young designers hunch over tables meticulously marking up their creations. It’s the kind of focus and precision you’d expect to see from a heart surgeon.

It’s less than five days until FashionEasta, a fundraising runway show and sale at the World Trade and Convention Centre in Halifax. Fashion design graduates from both the Centre of Arts & Technology and Nova Scotia College of Art and Design University take to the studios to work away at their collections.

These students make fashion a major part of their lives, just as many in the industry do: designers, manufacturers, marketers, and retailers. Fashion, like other art forms, can be inspirational. And it too can have respected journalists reporting through a cultured and artistic eye.

“If I talk about a Brahms string quartet and I say it’s very beautiful and how I react to it… people think I’m being clever and sensitive,” says Russell Smith. “If I talk the same way about how I react to a silk tie they say I’m being superficial… but I’m really describing the same set of aesthetic reactions.”

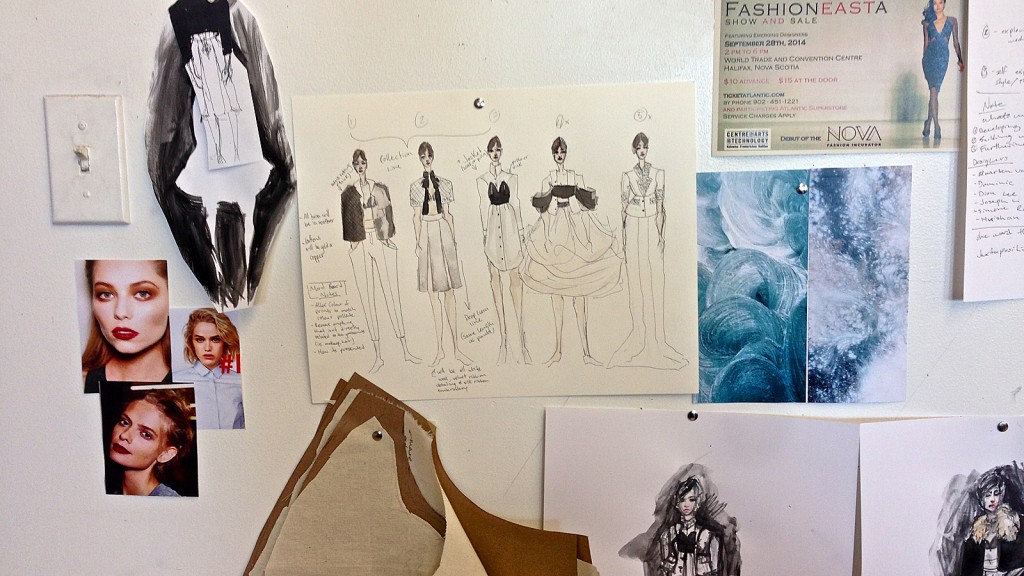

caption

A glimpse into the process of designing a collection shown above a work desk at the Nova Scotia College of Art and Design University.A man of many hats, Smith is a journalist and author, and teaches creative writing at the University of Guelph-Humber in Toronto. He’s recently finished his stint at the Globe & Mail after more than 10 years of cultural commentating and writing a men’s fashion column. Smith found when having conversations with academic friends they’re skeptical. What could be interesting about fashion.

Fashion journalists today continue to experience a lack of respect rooted in gender stereotypes, freebie concerns, and ignorance toward the intricate subject they cover.

“It’s such an enormous industry, it’s billions of dollars globally, it employs countless numbers of people,” says Alexandra Jacobs, fashion columnist at the New York Times. “It is something that is tremendously influential in the lives of young people, and it needs to be looked at critically and with distance.”

Since 2011 Jacobs has been one of the critical shoppers for the Times. She’s recently returned from her first tour of fashion weeks in New York City, London, Milan, and Paris. The craziness of the fashion bubble – a term to describe the imaginary bubble enveloping fashion week participants – is fresh in her memory.

Up to a dozen shows a day, it’s an overwhelming amount of stimuli to take in. With deadlines throughout the day, between shows and presentations, means fashion journalists have to focus on getting the story out with a fresh take, and quick.

Despite working for the top selling newspaper in the United States, Jacobs still feels judged for what she does because of the public’s “breathtaking prejudice” towards the Style section.

Recalling a dinner with other women working for the Times, Jacobs says she was shy when it came time to introduce themselves and what they did.

“Here I was in a room full of women who were covering banking, politics, foreign policy,” said Jacobs. “I have found myself apologizing sometimes, and then I try to correct myself. The fact is, like it or not, fashion is a tremendous industry and a tremendous part of the culture and it needs and deserves to be scrutinized.”

For something people participate in every day, fashion is often brushed aside as a silly, superficial waste of time and energy.

“It’s an uphill battle … covering the subject matter without being belittled or denigrated for it.”

-Karen Von Hahn, Toronto Star

“We have a dubious relationship to style. If things are nice we’ve spent too much money on it, it’s extravagant, and unnecessary,” says Karen von Hahn, who writes the Style Czar column in the Toronto Star. “It doesn’t have to be ugly and plain and cheap all the time, but in Canada we think that that’s more virtuous.”

Von Hahn responds quickly when asked if she’s felt disrespected because of her job. “Constantly! It’s an uphill battle in terms of covering the subject matter without being belittled or denigrated for it.”

When you open up the Style section of any newspaper, it’ll likely be directed to a female demographic. This doesn’t mean it’s not valuable to a wider audience. Conscious reporting on fashion, as opposed to press release regurgitations, provides a pool of potential new business ideas and initiatives to enlightened entrepreneurs.

By looking at what interests us and why, skilled journalists see a greater cultural trend. Von Hahn thinks of it as an anthropological exploration.

Fashion designers forecast our desires, and also expose our fears.

“They are making these choices two years before,” said Von Hahn. “Not only creating something beautiful that people want, but reflecting an internal desire.”

Take the recent trend of products oriented around organic materials and natural, handmade artisanal works. Von Hahn suggests this is arriving at a time in history when our culture is cluttered with hype and flashy bling. These products, she said, show our fear of being conditioned to the artificial, as well as our worry for what we’re doing to the planet.

“Fashion, like death and taxes, cannot be avoided,” says Gary Markle, assistant professor at NSCAD U.

Seduced by textiles at a young age, Markle attended the Parsons New School of Design in New York City. Design has been a part of his life since. The lack of respect fashion journalists face is no news to him.

“Anything can be treated lightly,” said Markle. “If fashion is treated well and intelligently, it’s gripping. It’s full of every nuance: murder, mayhem, intriguing backroom deals, all sorts of things.”

The assumption that fashion journalism is simply glossy images and talking about the latest handbag hinders the subject from being taken seriously.

Embedded in our culture is the idea that topics of muscle and masculinity merit more respect and attention than frothy female focuses. Markle believes fashion gets trashed because it’s aligned with the feminine and the feminine gets “thrown under the bus” more than the masculine.

“There’s the whole thing of how a powerful woman scares the shit out of everyone and is labelled a bitch, like the (Vogue editor-in-chief) Anna Wintour syndrome,” said Markle.

Haley Mlotek is taking on the role of editor of The Hairpin, an American women’s website. Recently she was a publisher, overseeing the twentieth and the final issue of Worn, an alternative fashion magazine based in Toronto.

Haley Mlotek on how fashion is perceived in the public eye

Describing the disdain she faces as “microaggressions”, she worries that people who disrespect fashion do it under the impression they’ll come off as more serious and intellectual. In addition, she believes dismissals are coated in misogynistic beliefs and gender stereotypes.

In Fashion Meets Journalism, a 2014 Masters thesis for the Queensland University of Technology in Australia, Shannon Wylie wrote, “The ideals of modern journalism concern the important economic and political affairs of the abstract public space of the nation. This space was (and often still is) predominantly occupied and shaped by male decision-makers. The value system of modern journalism has accorded a much lower status to fashion journalism, which attends to the softer pleasures and secrets of more feminised, private spaces of the home.”

caption

“Fashion journalists need to have an “editorial and I don’t think other journalists have to be.”The National Council for the Training of Journalists is a charity providing training for journalists in the United Kingdom. In 2012 the council added Fashion Journalism as an accredited course. Julie Bradford, leader of the Fashion Journalism course at the University of Sunderland, played a big role in this.

Bradford recognized accreditation was important for students because it’s a benchmark for employers in the UK. She didn’t see why a sports journalism course could be accredited and a fashion course couldn’t. Her students were given a trial year at the training organization and did extremely well. The council had no argument left not to allow accreditation.

The intensive course covers a wide range of topics: shorthand, reporting on catwalks, designing page layouts, writing for online, and the editorial eye. Bradford argues her journalism students are just as qualified as any others. “They know laws, public affairs, business, and are properly trained.”

Before teaching, Bradford was with the Agence France-Presse for five years. Some of that time was spent in Paris, where fashion and those who cover it are highly respected.

Prior to Paris she was in the Middle East, but fashion shows and cultural events were few and far in between. During her time there she reported on politics, war, riots, and suicide bombings.

“Sure you’re sipping champagne rather than dodging bullets, but it’s still important.”

– Julie Bradford, University of Sunderland

It wasn’t until her return to the UK that she was faced with negative reactions. People judged her for “going down a step by covering fashion.”

“Your job is to find out what’s important in that world, and show people who know nothing about it why it’s important. That’s the same whether you’re in Syria or Paris,” says Bradford. “Sure you’re sipping champagne rather than dodging bullets, but it’s still important.”

Much of the criticism towards fashion journalists stems from a general belief that they are public relations puppets who eat out of the hands of designers.

Nathalie Atkinson, recently hired as a columnist for the Globe & Mail, says a lot of fashion talk in the media doesn’t qualify as journalism. Fashion is lumped into entertainment news, benefitting brands and not the readers.

“There’s not a lot of tough writing on fashion in Canada, and there should be more,” says Atkinson. “There should be a lot more people stirring the pot. You have a responsibility to the readers.”

Some publications, like the New York Times, the Globe & Mail and Worn, have a zero tolerance policy for accepting gifts, to avoid bias and maintain independence.

Though proud of Worn’s policy, Mlotek would never judge someone for accepting gifts. Still, she thinks transparency is key, as it is for all journalism. “It’s just important to disclose these things and to be upfront about it. Recognize fashion has to hold itself to the same journalism standards as any other cultural writing or it’s not going to be taken as seriously.”

The Times critical shopper Jacobs covered fashion label Rag & Bone’s runway show. Despite liking the designs her review was critical. She found the venue too noisy and had difficulty focusing on the collection. In her mailbox soon after was a gift from one of the designers, a pair of Bose noise-cancelling headphones, worth more than $300. Though appreciative of the humour and the designer being a good sport, she sent them back to keep the line drawn.

Much of the judgment towards fashion journalists is subtle, perhaps in the form of a passing joke. “Cat shampoo” and “fashion journalism” – these are two examples of oxymorons a copy editor jokingly said to Jacobs.

“You can wash a cat. I’ve done it!” she said. “The point is that it’s difficult. There are natural forces working against you, but it’s not impossible.”

The same, Von Hahn said, goes for fashion journalism. She believes there’s inherent sexism and skepticism from both the public and other journalists, because they don’t understand the subject. It can be challenging to be heard above the cacophony of voices.

That doesn’t mean fashion journalism can’t be done, and done well.

“There are many reasons why this is a much more substantial pursuit than people recognize,” said Von Hahn. “It can be done shoddily, but there are people who do it better and with more substance. It doesn’t mean that the whole genre is without intellect or substance.”

Fashion coverage through the years

Editor’s note: This story was reported and written by Oct. 17, 2014.