Fisheries

Nova Scotians work to keep the art of net mending alive

Changing fishery means fewer people are mending their nets

caption

Kenny Henneberry stands with his sons Logan and Garrett in front of his brother's fishing boat at their family wharf in Sambro, N.S.As Nova Scotia’s fishery changes, some people worry that one of the industry’s oldest traditions — net mending — will be swept out to sea.

Garrett Henneberry, 19, of Sambro, N.S., has been fishing since he was seven. He first learned the fundamentals of the job through his father and uncle. Now, he fishes herring.

“Being a younger generation of fishermen, I want this to last for my lifetime and when I eventually have kids, I want it to be for their lifetime,” Henneberry says.

He’s keen to learn the skill of net mending, a practice he thinks could be forgotten if not passed down from father to son. Related stories

When his crew mends a net, they tie monofilament across the tears that develop, quickly patching them so they can be used again. This might be a quick fix, but with every patch, the net is shortened until it’s too small to use.

caption

The Henneberrys use monofilament fishing nets to catch herring.“There’s a right way and a wrong way to do it,” Henneberry says.

His father would usually begin by cutting a bigger hole and then weaving the material together in a pattern that resembles the rest of the net.

“You’d be better off doing it the way my father did it because you have more places fish can mesh into,” says Henneberry.

Kenny Henneberry, Garrett’s father, has been fishing and mending nets with his brother since he was a child. He says he often saw people fall behind because they weren’t able to repair their nets. Now that he’s retired, he’s focused on training his two sons to be successful fishermen by passing on the skill of net mending.

“There’s not a lot of fishermen, down the road, that are going to be menders,” he says.

“These guys are going to learn,” Kenny says pointing at his sons. “They haven’t got there yet. But they’re going to learn.”

Today, it is quicker and easier to buy new nets, but Kenny thinks that it’s an important tradition that will save his sons money in the long run.

Jack Mitchell at Rainbow Net & Rigging Limited, a common source of nets in the province, says the largest herring fishing monofilament net they sell, fully rigged up, costs around $340.

Garrett says fishing crews typically need 18 to 20 nets a year. If they buy 20 nets, that amounts to almost $7,000 annually.

Out of the ocean and into the museum

Aidan Smith, who works at the Maritime Museum of the Atlantic, agrees this skill should continue. On a quiet day at the museum, he can be found showing people how to weave full nets and mend holes by hand.

The techniques are the same but net making takes a lot longer. Smith says it’s tedious work, and not many people still make entire nets by hand.

He learned these skills from a retired fisherman who volunteers at the Fisherman’s Life Museum in Eastern Shore, N.S.

Smith says traditional nets were made from any natural material a person could find, like flax, manila hemp, cotton or hemp. The nets would then be treated with homemade pitch – a tar like mixture – to protect them from disintegrating in the salt water.

“It’s a part of Nova Scotian history,” says Smith. “It’s a craft that’s being lost. So I want to preserve it.”

The net making process was once a family effort, he says. When the season ended, families would hang their nets, or lay them flat, and mend them together.

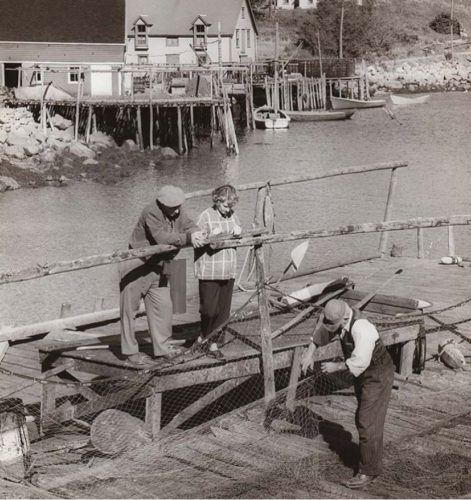

caption

Fisherman mending nets in Northwest Cove, 1956During his demonstrations, Smith encounters people from older generations who come from fishing backgrounds interested in reliving a taste of their childhood.

“It’s kind of nostalgic for them,” says Smith. “They remember a family member that used to do it or they wanted to learn but never did so they get to watch and give it a try.”

What was once a family effort is now a trip to a store to pick up commercially produced nets, often sourced from outside of Canada.

“The communities didn’t need to learn the skill anymore so it’s being lost,” says Smith.

From fisherman to mentor

“I’m just glad that there are these people, who work in the museums, and on the waterfronts and so on, and pass at least the wonder of it on,” says Robert Conrad, 73, of Fox Point, N.S.

“These are wonderful skills that are acquired with a lot of attention and it would be a tragedy for them to be not passed on to other generations.”

caption

Robert Conrad holds up a commercially produced fishing net.Several years ago, Conrad retired from a long career in fishing. He saw the practice of weaving nets from scratch, and by hand, disappear in the 1960s, as commercially made nets took over the industry.

People began to buy nets made of synthetic materials that lasted longer in harsh conditions. The downside of these materials is that they don’t decompose like their natural predecessors.

While he understands why people don’t make their own nets, he says knowing how to fix them is still critical to a successful fishing operation. He thinks net mending is a way to keep the vibrancy and mastery of the industry alive.

“When I look out at the water and see boats and schools of fish still, it reminds me of what can be and has been for numbers of families that help to populate this bay and other bays,” he says.

Currently, he’s mentoring a young person who is hoping to leave his career in engineering to enter the fishery. Conrad has already begun to teach him the skill of net mending.

“It’s a bit of an eye opener for me,” says Conrad. “I just assumed what they need to know is so basic, but it’s not, it’s something that they have to acquire and it takes time and practice.”

In Garrett’s case, he’s excited to take on the challenge. His dad plans to begin to teach him this season, but it could take a while.

For Garrett, it’s worth it to keep this tradition alive.

“You want to keep it going, not lose it,” he says. “I want my kids to learn how to do it the right way too, which is probably another really important reason that I think I should know, just to keep it going.”

About the author

Lucy Harnish

Lucy is a journalism student at the University of King's College. She hails from Mill Cove, Nova Scotia. Her interest in Russian literature led...

Amy Brierley

Amy is a journalism student at the University of King's College. She calls Antigonish N.S.--and more recently, Halifax-- home. She cares a lot...

s

sam parisi