On-site inspections become off-site

caption

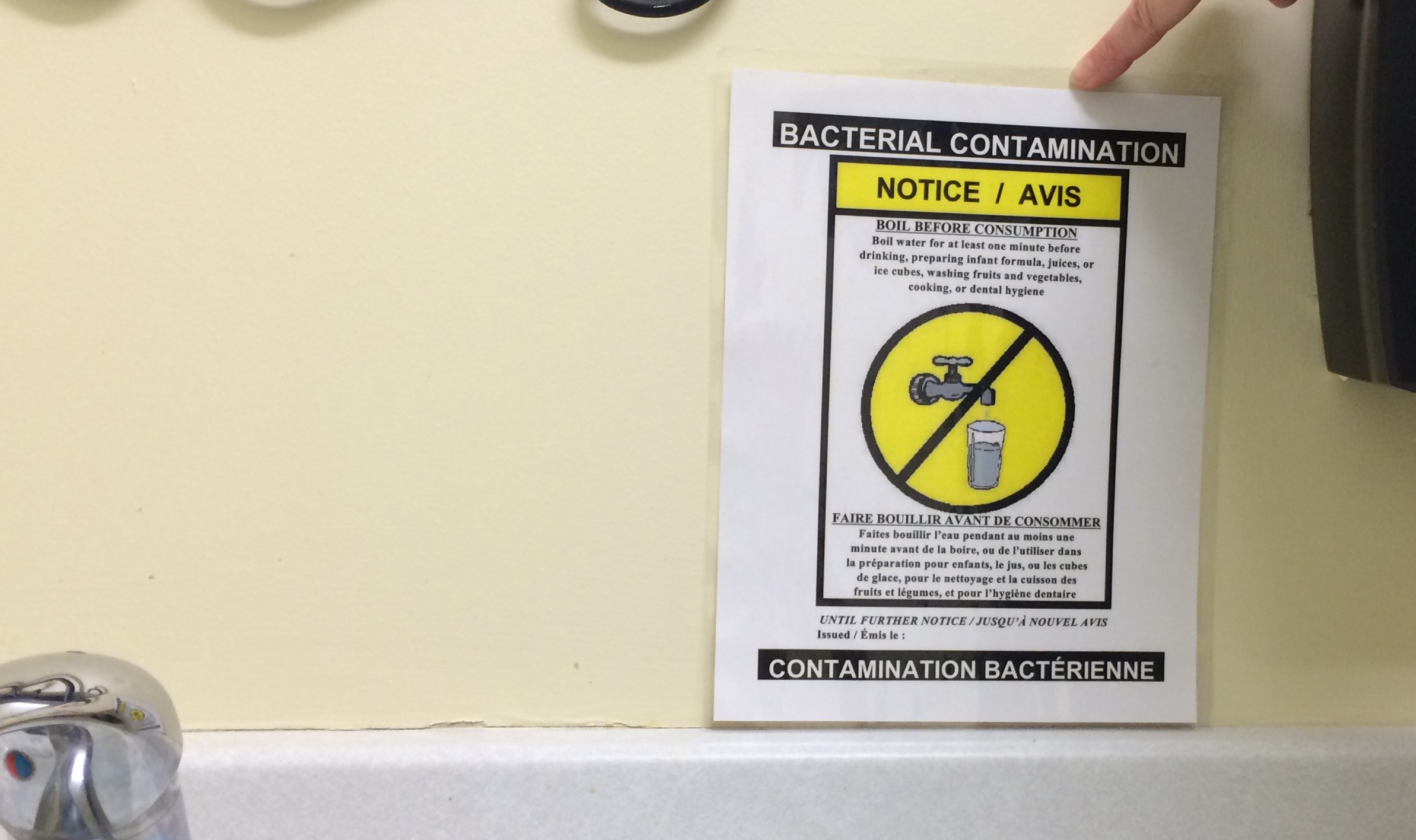

Facility owners, who initiated a boil water advisory, have to post a sign like this one beside every tap at the facility.When the well water is tested to have bacteria in it, the owner has to issue a boil water advisory to customers, reminding them the tap water can’t be used for consumption, food preparation or dental hygiene unless it’s boiled for one minute. To make that public, signs need to be posted over every sink at the facility. The inspectors, in the meantime, are supposed to go to the facility to make sure the signs are up.

During the Walkerton tragedy, warning signs was not broadly disseminated, so a lot of residents weren’t aware of the contamination, and continued to drink the tap water without boiling it, and ended up getting sick.

But Curtis-Steele says when the manager asks inspectors to limit travel, if inspectors still have a lot of inspections to finish, they’ll just call the owner to verify, rather than physically going to the site. But the inspection reports they put in the computer tracking system don’t indicate whether it is on-site or off-site.

Also, according to the Module 6, inspectors are supposed to conduct a follow-up inspection within 30 days after the boil order was lifted to make sure the tap water is completely safe to drink again. One of the most important procedure of that inspection is to take a water sample for bacteria.

But Curtis-Steele says when everyone’s trying to cut their travels at the end of the year so that the budget doesn’t go too far off, some inspectors will just phone the owner to make sure the water test results are good after the removal of the boil order.

Last year’s auditor general’s report points out inspectors didn’t complete the follow-up water tests at 45 per cent of the facilities it examined.

The report highlights the importance of the inspector’s confirmatory sample because it also identifies instances where unacceptable levels of bacteria have forced facilities to re-implement the boil water advisory after the removal of the first one.

However, inspectors have missed a lot of those follow-up samples.

According to the public accounts document, last fiscal year, the entire Environment Department paid $7,332.94 to Maxxam, one of the certified water test labs.

There are 255 boil orders issued from March 2013 to March 2014. If inspectors did a water test, as required, after every one of those orders were lifted, the department should have paid the lab at least $7,650, which is $300 more than the amount the entire department actually paid. This does not even include the 10 per cent audit samples and samples sent in by other divisions.

Overall, the department spent $11,032,000 on environmental monitoring and compliance last fiscal year. That’s $283,000 less than the previous fiscal year. Administration expenses, on the other hand, saw an increase of $209,000 during the same time period.