Parole system fails Indigenous prisoners in Nova Scotia, support workers say

Without access to culturally-specific assistance, parole can be worse than prison

caption

Patricia Whyte, photographed in Dartmouth on Dec. 10, is the Indigenous peer support worker with the Elizabeth Fry Society of Mainland Nova Scotia.Patricia Whyte knows firsthand what it’s like to be Indigenous and incarcerated.

Whyte is a Mi’kmaw woman from Cape Breton, and served four years in federal prisons including the Nova Institution in Truro.

Now, she uses that knowledge to help heal other Indigenous women who have been in prison.

As the Indigenous peer support worker for formerly-incarcerated women at the Elizabeth Fry Society of Mainland Nova Scotia, she organizes sweats for Indigenous women and teaches traditional beadwork, drum making and other traditional practices.

Whyte said she is the only Indigenous peer support worker in Atlantic Canada.

Inside prisons, many women have access to elders, sweats and sacred medicines. That support for Indigenous prisoners largely stops as soon as they leave prison, she said.

“Once they get out of the federal system and get out to a white halfway house staff to a white parole officer to a white program facilitator, they don’t have any of that.”

Without culturally-specific support, Indigenous people on parole fall through the cracks and end up back behind bars at higher rates than the general population.

In Nova Scotia, Indigenous people represented 11.2 per cent of custody admissions in 2019-20 despite making up only five to six per cent of the population, according to Statistics Canada.

Indigenous people fare worse in “every single correctional outcome,” according to Ivan Zinger, Canada’s Correctional Investigator.

They are more likely to be released at their statutory release date, serve time in a higher security institution, be subject to use of force, and be victims of self-harm and suicide, Zinger said in an interview.

Little support from halfway houses

Toby Condo is a Mi’kmaw man from Listiguj First Nation on Gespe’gewa’gi in Quebec. He spent 16 years in federal prison at a time when Indigenous prisoners had to fight for the right to practice their culture.

Now, he works at the Springhill Institution, a federal men’s prison, as a general population adviser and lives in Millbrook First Nation, N.S. In this role, he helps other Indigenous men connect with their culture through sweats, access to sacred medicines, and counselling.

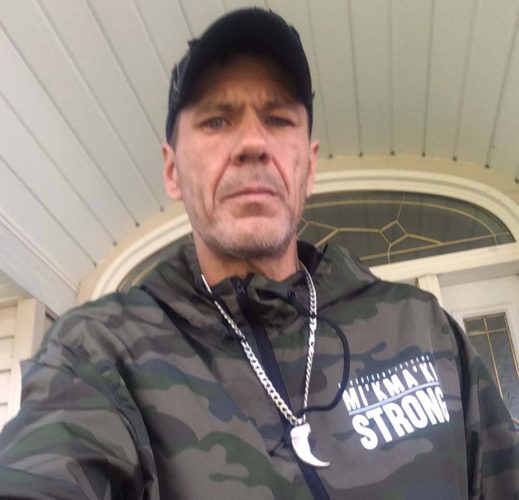

caption

Toby Condo is a general population adviser at the Springhill Institution. He said there’s not enough culturally specific support for Indigenous people after they are released on parole.“Every person I get, when I meet them, it’s like planting a seed in the ground,” Condo said.

“I’m going to have years to work and evolve and watch them grow … or watch them die. I see both. I see suicide. And then when they start growing, I’m with them, and I’ve got them feeling good about their culture, identity.”

Condo said that while things have been improving in prisons, there is very little support from the workers at most halfway houses.

“Most of them are non-native and have no clue what we’re about, they have no clue about our Aboriginal social history. They don’t even know what a sweat is, they don’t even know what medicines are,” he said.

“Our people are suffering when they come to the halfway houses, period.”

The law is meant to protect the rights of Indigenous prisoners, from initial intake to parole.

The federal Corrections and Conditional Release Act contains specific legislation to ensure that Indigenous people in the justice system have access to cultural programming and elders. The 2013 Strategic Plan for Aboriginal Corrections also says that parole officers receive training with “Aboriginal-specific components.”

In Condo’s experience, it doesn’t work like that.

“When you’re on parole, it’s like flipping a coin,” he said. “If they don’t want to work with you, you’re done. It’s as simple as that.”

These conditions are reflected in rates of revocation, when a person is returned to custody due to parole violations.

In Atlantic Canada over the last five fiscal years, 16.9 per cent of total designated offenders were sent back to prison for breach of parole conditions. For Indigenous designated offenders, the number was 23.4 per cent.

'It means nothing to them'

Part of the reason Indigenous people violate their parole more often is that they don’t feel supported after their release, according to Condo.

He said halfway houses push Indigenous people into Western forms of rehabilitation.

“I got to forget who I am, all my stuff that I’m trying to work on, in order to survive in this halfway house, become white,” he said of his own experience in parole in 2002.

Twenty years later, he said it is common to see officials at prisons and halfway houses teasing Indigenous people about taking drugs when they are smudging, just to “hassle” them.

He said more education for parole officers is needed.

“Why don’t they take them out to a place where they can go to a sweat lodge, understand our smudging?” he said.

“These people know absolutely nothing, and it means nothing to them.”

Whyte also experienced problems during her parole period, including conflict with her parole officer.

When she was first released in Cape Breton, she had a parole officer who she said didn’t care about her cultural needs. When she needed travel passes to go see her elder or attend a sweat lodge, her parole officer often didn’t get them done in time.

Whyte said her parole officer also pressured her to end her relationship with her partner, even though he was not involved in any sort of criminal activity.

When she complained about her parole officer, things got worse.

“Once I did that, and I went above her, she tortured me,” Whyte said.

Not long after, Whyte was sent back to prison after she was stopped by a police officer for being out late on Christmas Eve drinking with friends.

When Whyte got out of prison, she was assigned to another parole officer, who always made sure she had travel passes if she wanted to go to a sweat or see her elder, and attended her healing circle with the rest of her team every month.

She said having a knowledgeable and supportive parole officer shouldn’t be left up to luck.

“I feel like there are good parts of policies. However, I feel like the majority of that needs to be ripped apart and rewrote,” she said.

No improvement from corrections

In his 2018-19 annual report, Zinger did an investigation into Indigenous corrections. He produced 10 recommendations for CSC to improve correctional outcomes for Indigenous prisoners, including increasing the number of culturally specific resources, hiring more Indigenous staff, providing more cultural training for employees, and improving reintegration resources.

According to Zinger, CSC has not meaningfully applied any of his recommendations.

caption

The Jamieson halfway house is located in northern Dartmouth. Condo says the location has been planning to build a sweat lodge for five years.His first recommendation was that CSC reallocate more of their funding towards implementing a greater number of Section 81 and Section 84 agreements from the Corrections and Conditional Release Act.

The agreements allow an Indigenous prisoner to serve their parole under the custody of their Indigenous community, as opposed to being sent to a halfway house and assigned a parole officer.

Condo said that in the five years he has worked at Springhill Institution, he has only seen one person released with a Section 81 agreement.

“CSC needs to treat us better, more respect,” he said. “They need to respect the elders more. They need to respect culture more. They need to take more sensitivity (training).”

CSC spokesperson Pierre Deveau said they deliver a “broad-range” of culturally specific programming in consultation with Indigenous communities.

“Based on a healing and holistic approach, Indigenous programs target offenders’ needs in the context of Indigenous history, culture, and spirituality while at the same time addressing the factors related to criminal behaviour,” Deveau said.

Despite frustrations and burnout, Condo continues to do his work. He holds sweats in Millbrook. He continues to support all the men he has worked with in prison, and will answer their calls any time of the day or night.

“I go back just because I know how it is outside. I know how it is inside. I’m trying to pay it forward.”

Whyte continues her work at Elizabeth Fry and speaks about her experiences with the justice system at law schools, conferences and high schools to raise awareness about prison justice. She said she wants to encourage young people of colour to grow up and change the system from the inside.

“I go and speak at Grade 12 law classes because if they choose to be a parole officer, or even a correctional officer, maybe my story could stick in their head. It's gotta be changed all around, you know?”

Correction:

About the author

Sarah Krymalowski

Sarah Krymalowski is a journalist with The Signal. She has a bachelors degree of Arts & Science from McMaster University where she studied...

Victoria Welland

Victoria is a journalist with The Signal at the University of King's College. She is also a member of the news team at CKDU 88.1 FM. Originally...