Pulp mill’s warm welcome to Pictou County sealed fate of Boat Harbour

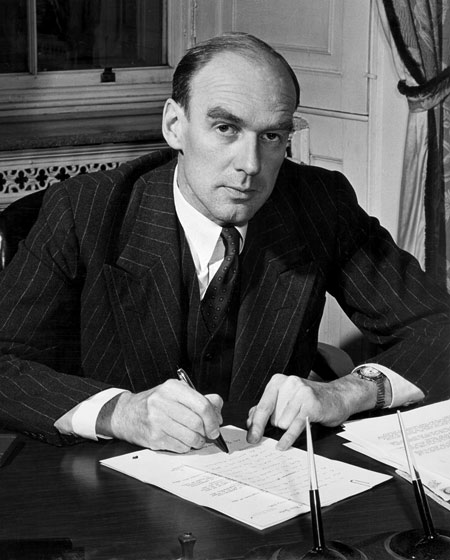

caption

The pulp and paper is still located on Abercrombie point.Natural tidal inlet polluted, never restored

Tuesday, Nov. 14, 1967 was a day of celebration in Pictou County, Nova Scotia. The Scott paper company was set to officially open a state-of-the art pulp mill. It brought 300 new jobs and millions of dollars a year in new economic activity to the area.

Employees gently laid white cloths over the tabletops, and set down trays of appetizers and dips for a celebratory luncheon. They placed a $90,000 scale model of the mill on a table. Men in white-collared shirts hovered around the model, fiddling with levers and tightening pipes.

At 11 in the morning, Premier George Isaac Smith and a long list of dignitaries would formally welcome Scott paper. They would then go on a tour of the $50 million mill.

It was good news for almost everyone. But not for those who lived or owned property near a little-known body of water called Boat Harbour. For them, life was about to change for the worse.

To produce pulp, the mill had to use 25 million gallons (112 million litres) of water a day. Once used, the water emerged from the back end of the plant as murky, liquid waste. It was the plans to treat that waste that would create for Nova Scotians an enduring toxic legacy, and seal the fate of Boat Harbour.

To find the roots of the story, King’s journalism students dug into the official records of the era, stored now at the Nova Scotia Archives. These included the personal papers of the premiers of the day, and meeting minutes of a long-forgotten body called the Nova Scotia Water Authority.

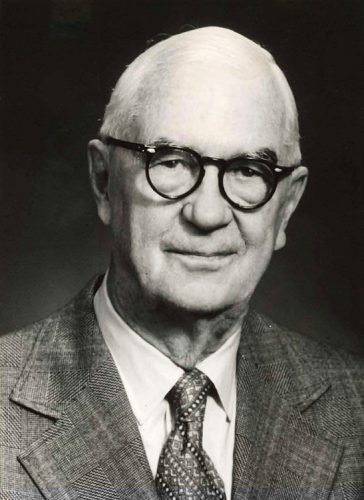

caption

Robert Stanfield.Robert Stanfield’s Conservative government created the authority in 1963 and gave it sweeping control over development of water bodies across the province. As one of its first acts, the authority set out to re-engineer the landscape around Pictou Harbour for the benefit of Scott paper. As well as turning Boat Harbour into a waste treatment lagoon, it dammed off the Middle River branch of Pictou Harbour to create a huge water reservoir for the mill.

Bob Christie, a Pictou-area environmentalist, said the area’s economy was in deep trouble at the time. “The coal industry was dying, the steel industry after the Second World War was going and gone, and we had a guy called Frank Sobey who was part of Industrial Estates Ltd., the part of government that handed out money to bring in industry,” said Christie. “And the industry they offered here was pulp and paper.”

Boat Harbour wasn’t really a harbour at all, but rather a tidal inlet from Northumberland Strait. The water authority said publicly the treatment lagoon wouldn’t harm the environment, that residents could practically drink the waste. But the story in private was different.

Minutes of the water authority show officials knew the waste flow from the new mill would be acutely toxic, and that the authority used Boat Harbour to keep that pollution from flowing directly into Pictou Harbour and Northumberland Strait. Though primitive by current standards, the waste treatment plan was revolutionary in one respect –the other four mills in the province didn’t treat their waste at all.

The Boat Harbour Scheme: meet Dr. Bates

caption

John Seaman Bates.The Water Authority’s first chairman, appointed with a salary of $10,000 a year, was Dr. John Seaman Bates. He was a chemist from the pulp and paper industry who helped set up mills across the country

At the time, Bates was head of both the Nova Scotia and New Brunswick water authorities and would later hold the job in P.E.I. as well. He would later receive the Order of Canada for his work in establishing the Technical Division of the Pulp and Paper Association of Canada and the Chemical Institute of Canada.

Robert Wood, the former executive director of the technical division (now called the Pulp and Paper Technical Association of Canada or PAPTAC) inducted Bates into the International Paper Hall of Fame in 2006. The two met at a dinner in the 1980s

“He is the type of leader who helped develop this country and gave jobs to people,” said Wood. “I can’t say enough nice words about him, a true gentlemen, polite; he could’ve had an ego the size of a truck but he was very down-to-earth individual right up to his 101st birthday.”

In 1964, Bates penned an essay called “Damage and Disgrace” for the Atlantic Advocate magazine. In it, he gave damning reviews of pulp mills and industrial polluters in general, and showcased large photos of grimy waterways with high piles of soggy pulp and dead fish—all from industrial waste. In one striking image, white piles of foam float over a dark river: this is exactly what Boat Harbour ended up looking like, months after the Scott mill opened.

Certainly, Bates and other members of the water authority had no misconceptions about what came out of the back end of paper mills. Bates told the water commission toxicity from bleach kraft mills was “very high,” the minutes record. “Tests with young salmon have shown that at least 90 per cent dilution is necessary.”

At a conference in Montreal, Bates said that used mill water “carries solids, solubles and toxic substances, often in quantity and condition too staggering for polite conversation.”

The fateful decision to use Boat Harbour as a kind of crude settling pond was made in a series of water authority meetings. They were held over the summer and fall of 1965 in a fifth-floor boardroom at the old Nova Scotia government building, not far from Province House in downtown Halifax.

While early discussion focused on dumping the wastewater directly into Pictou Harbour, Bates soon set his sights on Boat Harbour.

The Water Authority minutes refer to using Boat Harbour as “Bates’ scheme.” And quite a scheme it was. The lifetime paper industry employee envisioned Boat Harbour as a government-owned treatment site, where multiple industries could treat waste, and the area municipalities could dispose of human waste.

At a meeting in July, Bates said he had visited Boat Harbour with Scott paper officials. They were impressed and phoned Bates later to say the company approved of the plan. The water authority members agreed unanimously at that July meeting that Boat Harbour should be used to treat the mill waste.

“The plan at the time was for the whole Abercrombie Point to become an industrial complex,” said Chris Moir, who heads the environmental services branch of the department of Transportation and Infrastructure Renewal. “That was the day. That was economic development in the ‘60s.”

But before “Bates’ scheme” could be put into action, approval from the Pictou Landing band – and its protector, the federal Department of Indian Affairs – would be required. While the province expropriated other landowners adjacent to Boat Harbour, it couldn’t expropriate the band. The band would have to co-operate, and so would Ottawa. Discussions began in August, 1965.

caption

Armand Wigglesworth.In September, water authority manager Armand Wigglesworth reported to one of those downtown Halifax meetings that he had visited the “Micmac Indians at Pictou Landing.” He said the band had raised “four major objections” to using Boat Harbour to treat waste. The specifics of the objections weren’t recorded.

Bates had a blunt reply. It was “absolutely necessary,” he said, to use Boat Harbour, so as to protect Pictou Harbour.

The story of how the native objections were overcome has become almost legendary.

“The shenanigans that went on were almost criminal,” said Daniel Paul, an author and former bureaucrat with the federal Department of Indian and Northern Affairs who later persuaded the band to sue Indian Affairs over its handling of Boat Harbour. He said Pictou Landing band officials were taken to New Brunswick and shown what they were told was a similar, operating waste treatment facility. An engineer even took a drink of the water, saying the water at Boat Harbour would be just as pure. The problem was, it wasn’t true. “We discovered afterwards, at that particular place the (treatment) unit didn’t come into operation for two years after that visit” Paul said.

But the tactic worked. On Oct. 21, 1965, only slightly more than a month after Wigglesworth reported the band’s “major objections,” the band council passed a resolution accepting payment of $60,000 as compensation for lost fishing and hunting revenues and “other benefits from the Indian use of Boat Harbour.”

Wigglesworth officially reported back to the Water Authority in November that the necessary approvals had been obtained, and by September 2, 1966, a federal order in council confirmed the arrangement. Archival records show the province was angry with Ottawa because the order in council failed to give Nova Scotia the absolute control of Boat Harbour that it wanted. Still, it was enough to move ahead with Bates’ plan to convert Boat Harbour into a sewage treatment lagoon for Scott Paper.

It wasn’t long before other, non-native residents, got wind of the scheme. They weren’t happy.

In a letter to Premier Stanfield dated March 19, 1966, Joseph B. MacDonald, a doctor from Stellarton, ridiculed a suggestion, attributed to Bates, that Boat Harbour would be improved by turning it into a treatment lagoon.

“This claim of theirs—that Boat Harbour will be improved by damming—would be much more reasonable if they were going to dam Boat Harbour and then use it for the storage and propagation of sharks” he wrote. The presence of sharks, argued MacDonald, would make swimming difficult, but putting industrial waste into Boat Harbour would rule it out entirely.

King`s students also pored through records of the Pictou Town and Pictou County councils. The records show no evidence the province ever brought its scheme to councillors’ attention. Even so, one councillor in the Pictou Landing area heard rumours and wrote a letter to Bates, asking him to verify what he had heard, that the province was going to run a pipeline into Boat Harbour to carry the wastewater from the mill.

“It is hard to understand that this Company or anybody (sic) or corporation being given authority to pollute this body of water,” Henry Ferguson wrote. He argued doing so would turn the inlet into “a cesspool.” He worried for residents whose properties bordered Boat Harbour.

Ferguson copied his letter to Premier Stanfield. The premier, in turn, passed it on to W.S.K Jones and Donald Macleod, both past ministers under the Water Act. His note suggests he had expressed concerns earlier. “This is the sort of thing I was afraid of,” the premier wrote. “Someone should see Henry Ferguson and reassure him.”

Undeterred, the water authority pressed ahead.

An engineer in Truro prepared plans to dam off Boat Harbour from Northumberland Strait, and turn it into a two-stage waste-treatment facility. He reported it would cost less than $100,000, the exact amount depending on how the facility was configured. Meantime, the fiberglass pipe to carry the wastewater from the mill was estimated to cost $2 million. And a combination railway causeway/dam was constructed across the Middle River to create the enormous water reservoir. The pieces were falling into place for both a water supply, and waste treatment, for Scott paper.

The charge to the company for wastewater treatment would eventually be set at about $100,000 a year, and the same for the water supply. A bargain, said Christie, the environmentalist.

“Cheap wood, cheap land, cheap treatment. Cheap, cheap, cheap,” he said. “Even in the day, in the early 1960s, that whole sequence of buying water and treating it would have (cost) between five and $10 million in 1964 dollars.”

Christie learned firsthand Scott Paper’s side of the story.

“Walter Miller was the first plant manager at Scott Paper and before he died I had the opportunity to spend long times talking to him,” Christie explained.

Miller told Christie about company meetings held at one Scott Plaza in Philadelphia. “‘At the meetings we had there it was hard to keep a straight face’” Christie quotes Miller as telling him. “They couldn’t believe how stupid the government was up here.”

In 1966, before Bates’ scheme was completed, both Bates and Wigglesworth left the water authority, although Bates stayed on as a consultant. It was left to Bates successor E.L.L. Rowe, to actually start the flow of waste into Boat Harbour.

Rowe later became a controversial figure, with residents later telling a consultant looking into problems with the operation of Boat Harbour that Rowe refused to install aerators to help treat the waste because it would cost too much. When improvements were suggested by the consultants, Rowe told a news conference he’d rather spend the money on something else.

Within a few short years of its inception, Bates’ plan to save Pictou Harbour by treating toxic pollution in Boat Harbour, would explode into one of the worst environmental fiascos ever seen in Nova Scotia. In the years to come, the province would spend millions on treatment upgrades, consultant studies, and cleanup plans that led nowhere.

It truly became a toxic legacy.