Rebuilding Halifax after the explosion

By Laura Hardy, Kathleen Jones, Anastasia Payne and Kristen Thompson

A bin full of broken glass rests on Deborah Clark’s kitchen table in Hammonds Plains.

The glass came from the garden of the house she used to own on Union Street, barely half a kilometre from the epicentre of the Halifax Explosion. She doesn’t know for sure if it’s all from the disaster, but it’s a stark reminder of the lives lived, and lost, in the old Richmond neighbourhood.

caption

Glass collected by Deborah Clark near her home on Union Street.“Every time I’d go out and do something, no matter what I did, how short a time, how long a time, I always found something in the ground,” she said. “There’s bits of dishes, and bits of glass, and you know a lot of it is window glass.”

Clark’s experience of finding glass and other artifacts of the explosion is common on Union and other nearby streets — not surprising given that it was the area the explosion devastated most, and the neighbourhood had to be completely rebuilt.

That job fell to the Halifax Relief Commission.

The commission was established by federal order-in-council in February 1918. Two months later, the Nova Scotia Legislature gave it the power to rebuild the devastated district and spend millions of dollars in donated relief funds.

In June 1918, relief commission chair T.S. Rogers laid out the commission’s ambitious rebuilding plan to Halifax and Dartmouth city councils.

Clark’s old house was built in 1920, and like many others in the area, its story is told in the voluminous records of the relief commission. In 1921, the commission sold the newly built dwelling, with the buyer agreeing to payments of $50 a month, according to the records preserved by the Nova Scotia Archives.

caption

Deborah Clark’s former house on Union Street.By 1924, the commission owned the property again and leased it back to the former buyer for $35 a month.

Later, others rented the house before it was eventually sold again.

Sweeping powers

The provincial legislation gave the relief commission the power to expropriate, buy, sell or lease property as it saw fit. All choices the commission made were at its discretion alone. The bill was passed despite strong opposition from Halifax council.

The commission also administered pensions for those the explosion widowed or left unable to work. In rebuilding, though, it wanted a more uniform layout for the neighbourhood.

This process began with resurveying.

Peter Henry is an architect who lives near the bottom of the steep slope that runs down to Halifax Harbour. He says the commission did all of its own surveying to save time.

Prior to the First World War, the community did not prosper economically, according to Janice H. Miller in her chapter in one of the most important books on the Halifax Explosion, Ground Zero.

Owners often neglected their houses and the local water systems were substandard. During the reconstruction, however, the relief commission used the opportunity to modernize the failing water system.

caption

An aerial photo of part of the devastated area, taken in 1921, shows reconstruction underway.The commission saw the explosion’s aftermath as an opportunity for revival. The most famous example of the commission’s rebuilding project is the Hydrostone neighbourhood, located between what are now Novalea Drive and Isleville Street between Young and Duffus. Nicknamed for a brand of fireproof concrete building blocks used in the construction, today the Hydrostone stands as a symbol of the rebirth of the area.

The Hydrostone isn’t the commission’s only legacy, however. It used its wide powers to reshape the old neighbourhood down the slope to the east, which didn’t always make it popular with the survivors.

“The northenders firmly believed that all the money should be spent in the North End,” said Garry Shutlak, senior reference archivist at the Nova Scotia Archives.

The commission shut down the primary health clinic that had existed in the North End in lieu of a new public health clinic at Dalhousie University. This left northenders without a clinic within walking distance, according to Shutlak.

The commission also remade parts of the street plan, implementing parts of a bold scheme drawn up by Thomas Adams, a prominent urban planner of the day whom the commission hired (the Hydrostone was also a key part of his vision). One of the legacies of this scheme is modern-day Devonshire Avenue.

caption

Devonshire Avenue.The street was surveyed diagonally across the steep slope, to make it easier for both horses and cars to get up the hill. At the same time, a number of streets that once existed were erased from the map.

Today, the wide thoroughfare of Devonshire is a popular shortcut for suburban commuters on their way downtown and divides the community into upper and lower halves.

Henry lives on Veith Street, between Devonshire and Barrington Street. His house was also built in 1920 as part of the reconstruction effort.

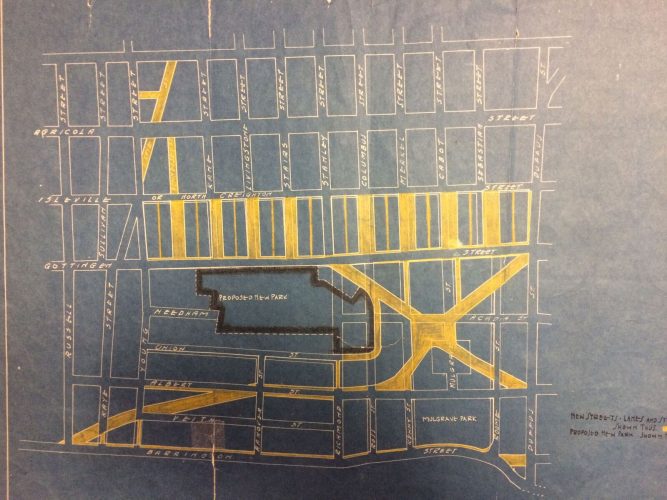

caption

A map created by the Halifax Relief Commission highlighting plans to reorganize the street network of the devastated area.“We’re always mindful that the explosion took place essentially in view of our front yard,” he said.

Ross and MacDonald, the architectural firm the commission employed, designed Henry’s house, along with several others on the street.

“The family that lived there before were all killed and the house was utterly demolished,” he said.

Like Clark, Henry has found bits of broken glass and pottery in his yard over the years.

“We found lots of styles of pottery, so you wonder, were they rich people who had lots of styles,” he said, “or were they poor people who had nothing that matched?”

caption

Peter Henry’s house on Veith StreetWhile living in her Union Street home, Clark found more than physical remnants of the explosion. She said she heard strange noises in her house, and that one night she felt a gentle touch on the back of her hand.

“You knew you weren’t by yourself,” she said.

“I just assume, and like to think, that they are the spirits of these people whose souls were lost that day.”

Another resident of 40 years, Pearline Byers, has also found shards of glass from the explosion in her backyard on Richmond Street.

But, she’s never kept any.

“If it was gold I’d keep it,” she said.

The Maritime Museum of the Atlantic has been collecting pieces from the explosion almost every year since 1917, according to Roger Marsters, the curator of marine history.

Following the explosion, the amount of artifacts the museum kept were significant, allowing the history to be preserved. Relief workers found and kept some pieces as souvenirs, while renovations in recent years uncovered others.

The museum has two exhibits: a permanent one entitled Halifax Wrecked and a temporary one called Collision in the Narrows, in recognition of the 100 year anniversary.

“I find it interesting as well, if you look at the character of the fragments collected in each decade, you can see the way that people have understood, appreciated or valued the fragments (and how they) have changed over time,” Marsters said.

caption

The site of the explosion is in the foreground, about where the blue door is located on the Irving Shipbuilding hall. The reborn neighbourhood once callled Richmond can be seen on the hill behind.In the years after the explosion, fragments were mounted or kept safe in drawers. It wasn’t until the 1950s that pieces started to become monuments, such as the Mont-Blanc’s cannon, hurled by the explosion to a site near Albro Lake in Dartmouth.

The fragments and monuments are what connect people today to the world that was lost.

“People renovating their houses find these items, and appreciate them as they form a tangible link between personal history, and history of the city and want to have those preserved for future generations, so they bring it to us,” Marsters said.

“So it changes over time, the way in which these items are understood, and the stories that are told about them, as well, all change.”

For people such as Clark and Henry the explosion is still a large part of their lives. The echoes of the explosion ring through their lives each day.

“It makes you sad,” said Clark, “but in a strange way proud, too.”