Mental Health

The ‘revolving door’ of seeking a diagnosis

How mental health bias can affect medical decision-making

Amanda Dodsworth spent three years trying to convince her doctor that her abdominal pain wasn’t all in her head. She’d visit him with the same complaints around four times a year – and face what she calls a “there, there approach.”

Dodsworth says she felt her complaints weren’t being taken seriously because of her previously diagnosed general anxiety disorder and depression.

One evening, the pain was so bad Dodsworth drove herself to the emergency department in Halifax.

Her gallbladder had ruptured. It was something she had already asked her family doctor about.

“At one point I even said, ‘listen I looked this up and it sounds like a gallbladder issue and I wonder if you could give me a referral for an ultrasound?’” she recalls. “And his response was, ‘who has the diploma on the wall?’ and ‘Amanda, it’s all in your head.’”

After her emergency department visit Dodsworth went back to her family doctor to tell him what had happened. But not too long after this, she says, he misdiagnosed her again, passing off cervical pain and abnormal menstrual bleeding as signs of aging, and telling her she was overreacting.

She insisted on a pap smear even though she wasn’t due for one for a couple months. When the results came back Dodsworth found out she had cervical cancer.

“I fired my doctor after cancer,” she said. “I told him he tried to kill me twice.”

‘Diagnostic overshadowing’

Cases like Dodsworth’s have become an issue in health care over the last couple of decades. One study in the medical journal, Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica, outlines the problem as “diagnostic overshadowing.” That’s when one diagnosis, such as a mental illness, overshadows the diagnosis of another illness, making it difficult to separate the two.

Multiple international medical studies – including the one that focuses on diagnostic overshadowing – have shown that people living with a mental illness receive worse physical health care than the general population. But it isn’t just a one-way problem. An article from the Journal of Psychosomatic Research states there’s also the issue of not recognizing patients who show physical symptoms as having an underlying mental health condition.

caption

Amanda Dodsworth was misdiagnosed twice by a doctor who refused to believe her symptoms weren’t all in her head.In these cases, the problem could actually be psychosomatic or somatic symptom disorders – physical illness that is caused by emotions or mental health factors such as stress.

Dr. Joel Town, an associate professor in Dalhousie University’s Department of Psychology and Department of Psychiatry, says somatic symptom disorders aren’t an all-or-nothing diagnosis.

“People can have bona fide medical conditions,” said Town, who also leads the Medically Unexplained Symptoms team at the Queen Elizabeth II Health Sciences Centre in Halifax. “But they can also have the level of symptoms of the experience can be over and above what you would expect purely based on the organic pathology.”

Not-so-special treatment

In Nova Scotia, Amanda Dodsworth isn’t the only patient who has experienced a tough time getting an illness diagnosed due to her past mental-health diagnoses.

Jace Miller wasn’t diagnosed with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder until he was 21 years old. He said the delayed diagnosis is one of the main causes for other mental health problems in his life, such as depression and anxiety.

There’s been a difference, he says, in how doctors respond to his symptoms of physical illness since he sought help for mental illness.

caption

Jace Miller has experienced bias when searching for answers for his physical symptoms due to previous psychiatric diagnosis.Miller, who identifies as transgender and uses the pronouns he and him, suffers from polycystic ovarian syndrome – a condition that causes severe cramping and abnormal menstrual bleeding. It took about a year for him to get properly diagnosed after fighting with his doctor to do tests. It wasn’t until he requested to go on hormones that a blood test revealed high testosterone levels – a sign of PCOS – which concerned doctors and made them do some more digging.

He also finds he is treated differently when he goes to an emergency department.

“Especially if you’ve gone in for mental health reasons – like I’ve gone in there for suicide ideation so they already know who I am – so if you go in there for another reason that’s always kind of there and it always kind of follows me around.” (Suicide ideation is another term used for suicidal thoughts and thinking about or planning of suicide.)

Miller says he felt like his concerns were being “pushed under the table,” and were all being “attributed to mental health.”

When the problem is ‘in your head’

It isn’t just mental health that’s overshadowing physical diagnosis. Physical symptoms are also masking mental health problems.

Katie Hartai experienced debilitating pain for months before doctors got to the root cause.

When she arrived at a Halifax emergency department, she described her symptoms: shaking, racing heartbeat, issues breathing, sleeping problems, nausea.

Bouncing between different emergency departments, Hartai was referred for a number of physical tests, such as an electrocardiogram. The results were all the same – normal.

“Doctors would say, ‘you’re healthy as a horse, there’s nothing wrong with you,’” she recalls. “But I knew something was wrong because I had never felt so crappy in my entire life.”

Hartai did not have a family doctor in Halifax to consult. “I just felt like I was running in circles because I wasn’t getting any answers and I think that only made these physical symptoms that I was experiencing worse.”

Finally, she left her job temporarily and headed home to Ontario. Her family doctor helped Hartai realize her symptoms were stress- and anxiety-induced.

caption

Katie Hartai produces The Rick Howe Show on News 95.7 in Halifax. She is thankful she has been able to return to her job.“It was a little frustrating knowing that in a sense I had done this to myself,” she said. “But I was also kind of relieved that she was convinced this was the problem. I was also scared, though, because I didn’t know how I could begin to solve such a big issue. It was just overwhelming at the time.”

Trying to get it right

Dr. Joel Town’s job is to come in when patients like Hartai feel overwhelmed, and to help with the treatment of physical symptoms that are stress- or emotion-based.

He conducts an assessment to determine whether or not physical changes occur when a patient discusses different emotions. There are three possible outcomes.

A patient can be determined to have physical symptoms caused by stress or emotions, or it can be determined that more medical investigation should occur because there isn’t a connection between stress or emotions and the symptoms. The other outcome is an inconclusive result, and the assessment process can be repeated to try to find a more conclusive diagnosis in either direction.

“We try to be wary of false positives or false negatives in just the first meeting,” he said.

For Hartai, who was referred to Dr. Town, the initial session was the hardest part of the process.

“It was also very frustrating,” she said. “I wanted to leave midway through the first session because he was asking questions that I didn’t have answers to.”

Through sessions with Dr. Town she was able to think about some of the habits she had developed and began to recognize emotional triggers for her physical symptoms.

“I was kind of helping myself, it was just he was guiding me to find these answers,” she said. “I realized what really bothers me and how I don’t necessarily deal with my emotions because I don’t accept to feel them all the time, and that’s a problem.”

Dr. Town says it’s common for doctors to be hesitant to diagnose cases such as Hartai’s.

“Clinicians and particularly physicians,” he said, “are actually very concerned and are actually more likely to under-report and under-diagnose and not refer people for potential assessments of somatic symptom based conditions because they’re frightened of getting it wrong and missing something.”

caption

Dr. Joel Town founded Dynamic Health Psychological Services in Halifax. The clinic specializes in Intensive Short-Term Dynamic Psychotherapy, used to treat somatic symptom disorders.Another problem Dr. Town and his colleagues face is when people don’t want to accept that their symptoms might actually be psychosomatic.

“We don’t want to force anything on people,” he said. “It’s counterintuitive to try and tell somebody – and unhelpful, actually, to tell them – what they think is wrong. And if somebody has a fixed belief that their symptoms are related to stress or not related to stress, then there’s a reason for that.”

Impact of bias

Stories about misdiagnosis – of both physical and mental illnesses – have been circulating more frequently in recent years, with the help of social media. There are no statistics on the number of Nova Scotians who are misdiagnosed every year.

Dr. Pat Croskerry, a researcher and professor in the Critical Thinking Program at the Department of Emergency Medicine at Dalhousie University, has spent the last five years educating medical students about how cognitive bias can affect how doctors diagnose patients.

Dr. Croskerry said psychiatric illness is a common reason that diagnostic judgment can be clouded. He refers to these mistakes as “psych-out errors.” Although he says that it would be difficult to study how many incidents are actually misdiagnosed, this is recognized as a source of medical error in psychiatric patients.

“It doesn’t just happen with psychiatric patients. It happens with all patients, but psychiatry patients are probably a bit more vulnerable than most,” he said. “Sometimes their diagnosis is challenged by the fact that they’ve got a psychiatric history and that shouldn’t interfere with diagnosis – but we know it does.”

A growing mistrust

One mental health advocacy group on Facebook, #HowManyNSHA-IWK, has petitioned the government to address concerns about the state of mental health care in the province. Specifically, the group wants an inquiry into hiring practices of mental health directors at the health authority.

caption

A post by Laurel Walker in the public Facebook group #HowManyNSHA-IWK shows what the petition called for.The petition was presented by a group of Conservative MLAs at Province House. Yanna and Russ Conway, who spoke at Province House during the presentation of the petition, lost their son, Garret, to suicide a year ago.

The Conways’ main concern is a lack of communication on the release of their son from hospital, when he sought help after an attempted suicide. Others have expressed similar concerns about being sent away after they have sought help.

CBC Information Morning aired a story featuring the Conways’ appearance at Province House and mental health advocate Laurel Walker, an administrator of #HowManyNSHA-IWK. Walker discussed how she has been hearing that people feel unheard, unsupported and not believed.

“They’re being told that if you decide to go kill yourself, you know, that’s your choice, we can’t keep you safe,” she said to CBC.

To be turned away from the one place that you think might help you, and they don’t want to believe you – that’s the problem. Carol Bernardo

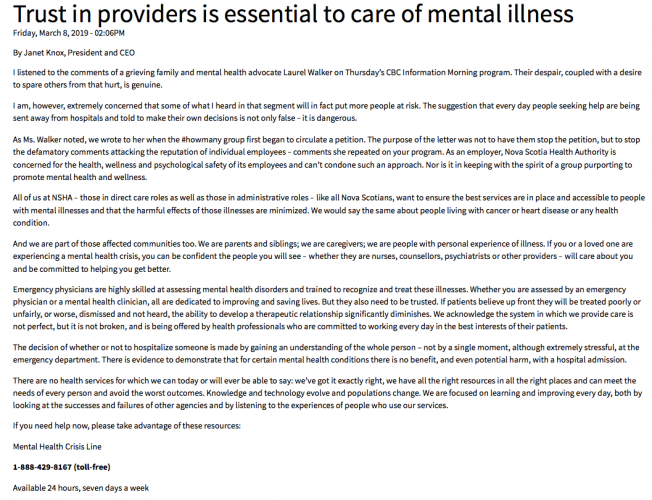

Nova Scotia Health Authority president and CEO, Janet Knox issued a statement on the authority’s website after the story aired.

caption

The Nova Scotia Health Authority’s statement on the need for trust in mental health care.“I am, however, extremely concerned that some of what I heard in that segment will in fact put more people at risk,” she wrote. “The suggestion that every day people seeking help are being sent away from hospitals and told to make their own decisions is not only false – it is dangerous.”

The authority’s mental health co-lead, Andrew Harris, echoed these concerns about possible misdiagnosis and patients’ mistrust,

“Our role and our function is to provide care to those that need it,” said Harris. “If people are not coming or not seeking our services because they feel that they are not going to be heard or listened to, that’s a real problem for us.”

Harris said that medical services are built on trust – trust that doctors know what they are doing and that they are professionals.

In addressing the advocacy group’s petition, Harris said that he doesn’t feel it is fair to put the blame on one person or to suggest there’s a leadership problem.

“I think it’s a bit of an overreach … to identify someone as being at fault for the totality of the system,” said Harris.

When it comes to mental health services, Harris feels that there is more of an “attitudinal problem” than an access problem causing issues with diagnosis.

A change in attitudes

Carol Bernardo has encountered these attitudinal problems first-hand when seeking medical help. As a former addict and someone living with post-traumatic stress disorder and borderline personality disorder, Bernardo feels these labels have affected her treatment.

“As soon as they know that,” she said of her previous addiction problem, “they shut right down.”

In a span of two weeks, Bernardo said she visited the emergency department five times because of suicidal thoughts and was sent home every time. Emergency department staff assumed she was there to try to get access to drugs, she says, and send her away. She also recalls being told that if she killed herself, it’s her choice and there’s nothing they can do about it.

“It’s almost like the revolving door,” said Bernardo. “If I thought my issues were resolved in the way they should be, I wouldn’t keep coming back and looking for help.”

Whether she seeks help for a physical or mental illness, she hasn’t quite felt like her concerns are being heard or treated because she feels she’s been deemed a “frequent flyer.”

However, the health authority’s Andrew Harris said there can be a disconnect between the treatment patients expect and what doctors decide is needed. “One does not necessarily meet the other.”

caption

Carol Bernardo works as a volunteer first responder and works with Sheep Dog to provide mental health services to other first responders.As a volunteer first responder, not only has Bernardo sought help – she has given help when needed.

“To be turned away from the one place that you think might help you, and they don’t want to believe you – that’s the problem,” she said. “The whole preventative medicine thing, that’s where they should be aiming, not when something catastrophic happens.”

What’s the prescribed fix?

Busy emergency departments in Halifax could be to blame for misdiagnosis or poor treatment.

“People tend to resort to shortcuts in clinical reasoning,” says Dr. Croskerry. “So you’ve got to be careful, that a system isn’t overloaded and that it’s well-resourced. If you have a shortage of doctors then clearly it’s not well resourced.” He cautioned, however, that he could not say whether this is a problem at Nova Scotia hospitals.

Harris wants to reassure people that, if they need medical help, they will receive it. Everyone who goes through the emergency department “will get a thorough and complete and appropriate assessment.”

Anyone worried about their health – mental or physical – should seek help, Amanda Dodsworth says.

“Know your body, trust your own instincts, and worse-case scenario a doctor runs tests and it comes back as nothing,” she said. “You’re the one responsible for your health in the end, so trusting yourself is really important.”