To understand and be understood

caption

Access to French-language health care services remains a cause célèbre among francophone Nova Scotians

A trip to the hospital can be worrying enough. For Éloïse Baïet, there’s one more troubling factor: the language barrier. For the birth of her first child at the IWK Health Centre in 2014, Baïet requested service in French. What followed, she says, was “not a great experience.” The interpreter provided spoke French well enough, Baïet says, but offered little assistance.

“She saw our English wasn’t too bad,” says Baïet, “so she did not take any interest in translating anything when she saw that we understood, more or less.” Baïet explained that during the birth, the interpreter settled into a nearby armchair to read a novel and was eventually asked to leave. For the birth of her second child, Baïet decided to try her chances in English.

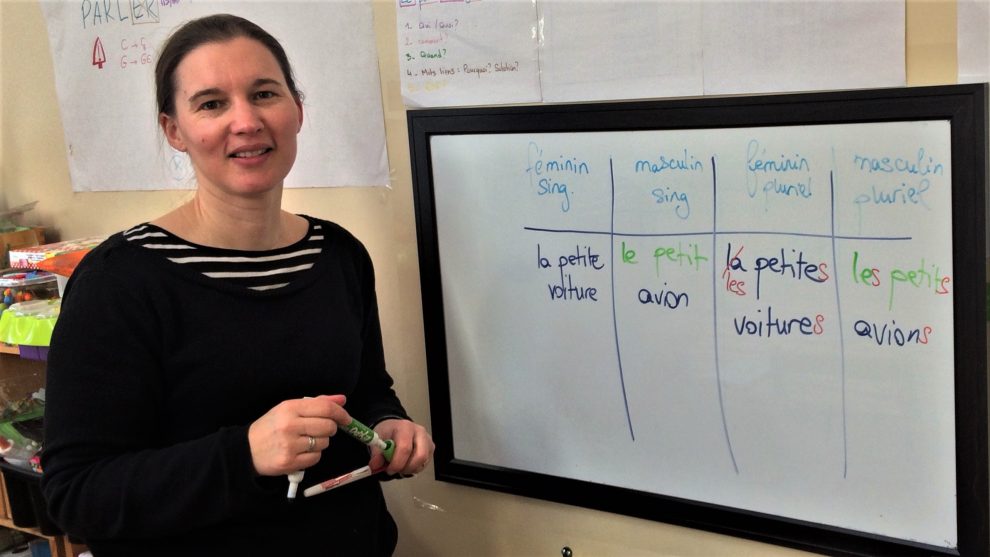

Originally from Dieppe, France, Baïet moved to Halifax 11 years ago. She was drawn to the region’s Acadian roots, and because it was somewhere that she could teach French, as well as work on her English. After working with the province’s francophone school board, and La Cité Language School, Baïet now runs her own daycare for francophone children in the city. For her, French is still her primary language of living and working. She describes her English level as “intermediate.”

caption

Éloïse Baïet says interpretive services will never replace French-speaking health care professionalsBaïet’s hesitance to demand service in French points to a broader trend among francophones in the province. In August 2018, Réseau Santé Nouvelle-Écosse, a non-profit group aiming to make French-language health care services more accessible to francophone Nova Scotians, published a report based on a survey circulated the previous month. Of the 99 francophone Nova Scotian who responded, 81 per cent stated they were not offered French services during their most recent visit to a health facility under the Nova Scotia Health Authority or the IWK Health Centre. Eighty-four per cent of this group did not request service in French, and more than half claimed their hesitation was due to a lack of indication that French services were available.

Some of the other common reasons that led participants not to ask for French services point to a disillusionment with the state of French language health care accessibility. Responses included the belief that asking for French service would result in a longer wait, and that bad past experiences of asking to be served in French during previous visits had kept them from asking again. As for the 16 per cent who did ask for service in French, none indicated they had received it, due to a lack of available staff.

The first job is to transmit the pain or the problem. Even at the intermediate level it still takes effort to speak a language. We don’t have the time or the energy to put this effort toward language.” Éloïse Baïet

Providing service in French

What sets Nova Scotia’s francophone population apart from the province’s other linguistic minorities when searching for health care services in their mother tongue is the authority of the French Language Services Act. Passed in 2004, one purpose of this provincial legislation is to “provide for the delivery of French-language services by designated departments, offices, agencies of Government, Crown corporations and public institutions to the Acadian and francophone community.” The act established the Office of Acadian Affairs and Francophonie to support these government institutions and ensure the needs of francophone Nova Scotians were being met.

One of the initiatives started by this office is the Bonjour! Program. It encourages French-speaking government employees – including those of the health authority and the IWK – to actively offer French service to the best of their ability, and provides logos on signs, posters and lapel pins to indicate French language services are available. Acadian Affairs also provides translation services and coordinates French-language training for government employees.

caption

Katherine Howlett’s Bonjour! sign, posted on her office door, shows she can offer service in FrenchSome of the French-language services available through the health authority include translations of its patient pamphlets and webpages, as well as access to broader interpretive services like in-person interpreters provided by Nova Scotia Interpreting Services.

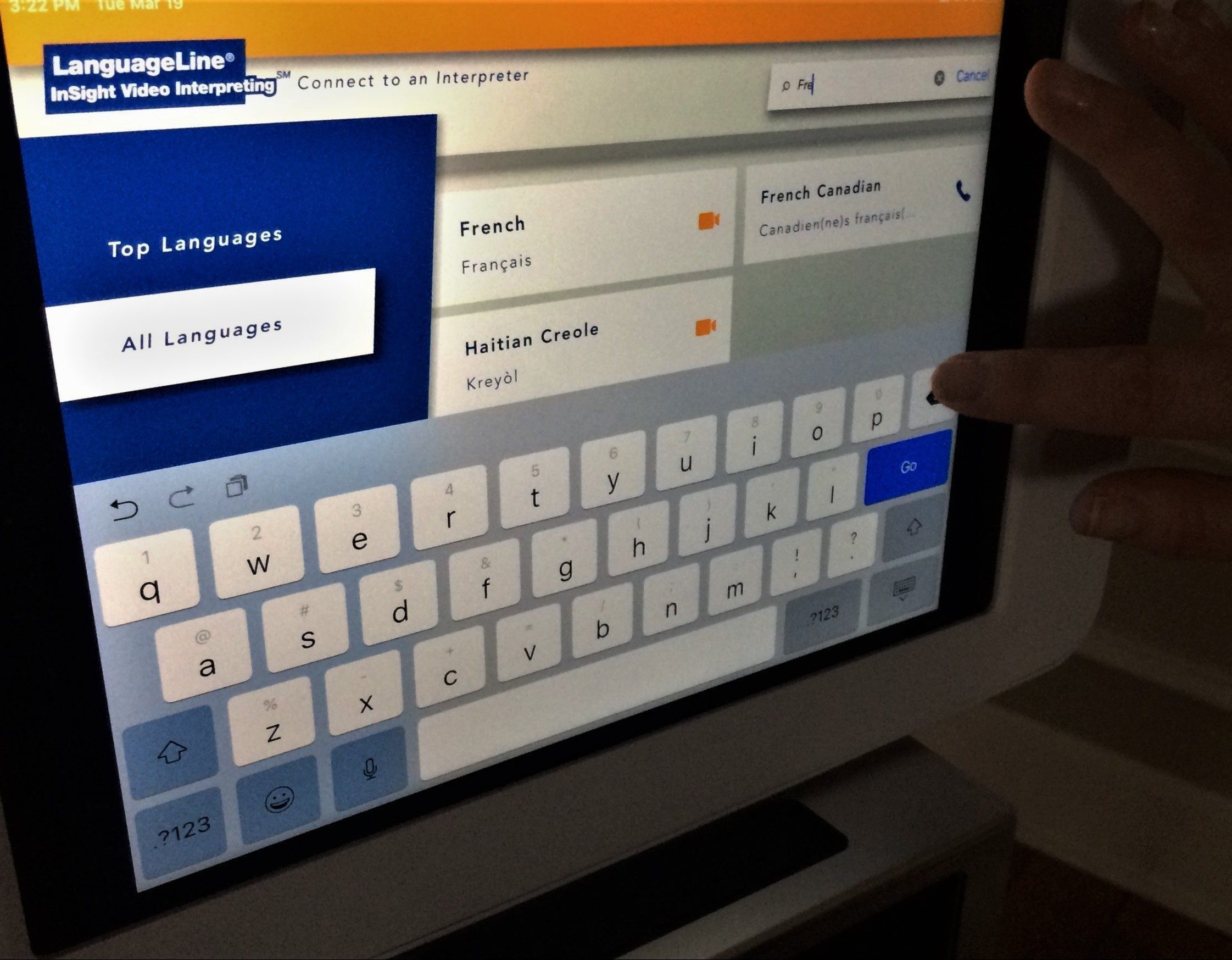

One recent development is the video-call interpretive service provided by LanguageLine, an audio and video translation company which employs interpreters with health-care training. The service, which debuted at the authority within the last two years, takes the form of an iPad mounted on a portable stand with an external speaker. On the iPad, hospital staff can access the LanguageLine app, which boasts video interpreting in 36 languages (including American Sign Language) and audio-only translation in 240 languages, from French to Moroccan Darija. Though the iPads and their portable stands are in limited supply, the service can be accessed from any smartphone or computer by health authority staff, with audio-only interpretation available via any telephone.

Nicole Holland, the interpretation and language services coordinator for the authority, says a protocol is followed when a non-English-speaking patient arrives at one of its facilities.

“Let’s say a patient does not speak enough English to say what they speak,” she explains. “We provide this language service card to them and they just point to their language when they see it.” She presents a brochure with the same phrase translated into different languages and scripts. The phrase reads, “point to your language and an interpreter will be called, the interpreter is called at no cost to you.”

After a language is selected, the health-care provider looks up the language on the LanguageLine app and calls the interpreter. During the video call, an interpreter repeats word-for-word the questions and instructions of the health care professional and relays the patient’s responses back to them.

When asked if these translation services would ever take the place of having a French-speaking doctor, Éloïse Baïet was doubtful, saying that though the translators may be proficient, and even have a working knowledge of medicine, they will never take the place of a fluent professional.

“We really don’t need an extra person,” says Baïet, referring to the hectic atmosphere of an emergency hospital visit. “It delays things to have to go through someone who re-explains, re-explains, and re-explains. It’s always going to delay the information.”

Baïet believes the best course of action would be to train doctors to speak French to their patients, though she admits that as a French teacher, she may be biased. There is currently no initiative to hire francophone or bilingual staff at health authority or IWK facilities, apart from the general statement at the bottom of the “Qualifications” list on their online job offers: “Competences in other languages an asset, French preferred.” However, employees do have access to free French training through distance courses in collaboration with Université Sainte-Anne, Nova Scotia’s only francophone university, based in Pointe-de-l’Église.

“There are few roles that actually require French,” says Katherine Howlett, the French-language services coordinator for the health authority. She points to her role as well as Nicole Holland’s, along with school nurses with the francophone school board as examples of health-care jobs where a knowledge of French is mandatory.

caption

French is one of the 240 languages accessible through the LanguageLine telephone interpreter service, and one of the 36 accessible through its video interpreter serviceBaïet’s concern echoes that of Nova Scotia’s broader French-speaking community. Pierre Roisné, the general director of Réseau Santé Nouvelle-Écosse, called the lack of French-speaking health care professionals a “key issue” when referring to the feedback his organization receives from the province’s Acadian and francophone communities.

Beyond the health authority

One limitation of the French Language Services Act is that it applies only to provincial government institutions. For francophones searching for French-language health care providers outside of the health authority and IWK, few tools are available.

One tool, however, is a directory of French-speaking health care professionals curated by Réseau Santé Nouvelle-Écosse. Accessible from the organization’s website, the directory allows Nova Scotians to search for specific health care providers such as family doctors, dieticians and physiotherapists who can serve clients in French. There are 23 French-speaking doctors listed in the directory – six in the Halifax Regional Municipality – with eight working in the province’s Acadian communities such as Chéticamp, Arichat and Centre-de-Meteghan. When Éloïse Baïet first arrived in Halifax, she promptly set out to find French-speaking health-care providers using the online directory.

“I looked for a dentist, a psychologist, a family doctor,” says Baïet. “I found a dentist, and a doctor who was too far from where I lived, so it wasn’t possible.” Another obstacle in Baïet’s search for a French-speaking doctor was that few were taking new patients. Some had even retired since adding their name to the directory. She eventually settled on an anglophone family doctor.

caption

French is still the primary language Éloïse Baïet uses in her personal and professional life in HalifaxBaïet’s francophone dentist is Dr. Mariette Chiasson of Santé Dental, a family dental clinic in downtown Halifax. Along with Dr. Melanie Fredette, Chiasson works in both French and English to serve patients and provide them with translated paperwork. Though French speakers make up a minority of her clients, five per cent by her estimate, she says it seems like she’s speaking French at work every day. Chiasson is also aware of the importance French-language health care services hold for the wellbeing of her patients.

“They reach out more if they feel that they can express themselves,” says Chiasson. “And when it’s not a chore to express themselves, you know that what you’re expressing is going to be accurate, and it’s going to be received accurately.”

Chiasson also says the security of French-language health care could even prevent future health problems for her patients. “It serves for people to not hesitate, to come when they have even the slightest concern,” says Chiasson. “They don’t wait for that slight concern to become something that they just can’t avoid.”

Questions of fluency

One potential reason for the apparent lack of urgency in promoting French-language health care could come from the statistics. According to the 2016 census, 10,140 residents of HRM list French as their first language, and 350 residents listed French as the only official language they speak. In the whole province, 29,465 Nova Scotians list French as their mother tongue, and for 705 residents it is the only official language they speak. However, 49,575 HRM residents indicate a knowledge of both official languages, with 95,380 in the whole province. This suggests many of the francophones in HRM and Nova Scotia at large are bilingual and equally comfortable in English.

People’s lives are at stake. In a bilingual country like Canada it is essential that everyone can be understood by speaking in the official language of their choice!” Health care survey respondent

But Pierre Roisné explains that the term “bilingual” can be misleading, particularly in a health-care setting. He says that in the event of a health crisis, or any stressful situation, francophones who consider themselves bilingual may lose their capacity to effectively explain themselves in their second language. This also applies to elderly patients who may have Alzheimer’s or other forms of dementia. “It is difficult to find your words,” says Roisné.

It’s a phenomenon Baïet is familiar with. After asking her ineffective interpreter to leave during the birth of her child, doctors informed her they would have to perform a C-section. With her intermediate level of English, she thought the procedure was an emergency that required fast action and was too overwhelmed to ask why the final delivery ended up taking an hour. It’s an hour she likens to “an eternity.”

“If we were in France, I would have said, ‘okay, it’s been 30 minutes since you told me it’s an emergency and it still hasn’t happened?’ and we wouldn’t have had a problem,” says Baïet. “But I think that the stress and the language barrier didn’t help.”

She says that, in a state of shock, the most important thing on a person’s mind is not the quality of their English. “The first job is to transmit the pain or the problem,” says Baïet. “Even at the intermediate level it still takes effort to speak a language. We don’t have the time or the energy to put this effort toward language.”

Being from France, one thing separating Baïet from many French-speaking adult Nova Scotians is her French-language education. With the establishment of the francophone school board, the Conseil scolaire acadien provincial, only in 1996, many older francophones in the province did not receive formal French schooling. Although French is their mother tongue, and the language they are most comfortable expressing themselves in, some are hesitant to request French services out of worry that they will not understand the French medical terminology, or that their particular dialect or quality of French will not be understood.

caption

French is one of many languages the health authority aims to make more accessibleIn Réseau Santé Nouvelle-Écosse’s 2018 report, some of the reasons offered for why participants had not requested French service on the province’s 811 line were that they were not comfortable with the French medical terminology, and that they were worried the person might not understand them.

“In an elderly population, they’re not too keen on the interpretive services,” says Katherine Howlett. “But the beauty with these services is that there’s more than one interpreter,” she adds, saying that in the event of a misunderstanding, patients can choose from an array of French-speaking interpreters until they find one who better understands them. It’s a rare event, but not unheard of. One of the participants in Réseau Santé Nouvelle-Écosse’s survey indicated that after being offered service in French, they were unable to understand the person who spoke French with them.

The importance of understanding

The issues surrounding access to French-language health care services in Nova Scotia come down to questions of availability and quality. Many francophones are unaware French service is an option at health authority facilities, and when they receive these services, they’re seen as more inconvenient or sub-par.

Despite this, a clear majority of francophone Nova Scotians value in being served in their mother tongue.

Sixty-nine per cent of participants in Réseau Santé Nouvelle-Écosse’s survey indicated that having access to French-language health care service ranged from “Very Important” to “Essential.” Some of the written responses to the question “Why is it important (or not) for you to be able to speak French in a health facility?” include comments about the importance of understanding and being understood by health professionals, as well as feeling more at ease in their native language.

Participants also raised points about their right to French services, with one response being, “People’s lives are at stake, in a bilingual country like Canada it is essential that everyone can be understood by speaking in the official language of their choice!”

“I think that if we can have access to medical and legal professionals in our native language, that changes many things,” says Éloïse Baïet, “because one medical or a legal error could change your life completely.”