Church Closures

Saving Saint Patrick’s

caption

Parishioners of the aging church hold on to ‘home’

Saint Patrick’s Church parishioners sift through old records and books at the church’s fundraising yard sale.

Blair Beed waits close by, to see if anyone purchases anything. Part yard sale co-ordinator, landscaper and janitor, he helps out the church however he can.

Today, he accepts a few dollars for the second-hand goods. The small bits of change go towards maintaining the church, but this isn’t enough.

What the parish really needs is $3 million.

Saint Patrick’s is falling apart. The 131-year-old church on Brunswick Street needs extensive and costly repairs.

For nearly a decade, Beed and other parishioners have been working to save the building. The Archdiocese of Halifax-Yarmouth has given them another 20 years to come up with the necessary money, but they face an aging population and structure.

“We’re doing it like an octopus,” Beed says.“We’ve got our arms going every which way.”

caption

Saint Patrick’s parishioner Blair Beed.A century’s worth of history

The church, which has both provincial and municipal heritage status, has stood for over a century. Built by Irish immigrants between 1883 and 1885, Saint Patrick’s was the only North End church to survive the Halifax Explosion of 1917.

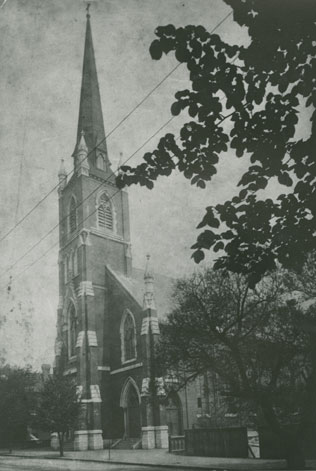

caption

The rebuilt Saint Patrick’s Church opened in 1885 (Nova Scotia Archives)For Beed, the church holds family history.

“My great-grandmother baked pies to build this church,” he says. “My grandparents went here; my parents went here.”

He remembers being a kid and going down the narrow stairs to the church’s basement to see his grandfather who managed the church’s credit union from a wicket downstairs.

“My grandfather used to reach over and take my quarter for the Saint Patrick’s credit union,” says Beed.

For 78-year-old Douglas O’Neill, the church is a second home.

“This has been my church since day one,” Douglas O’Neill says. He was baptized at Saint Patrick’s and married his wife, Theresa, there in 1959.

Their daughter Michele O’Neill later married in the church and is now the chair of parish life at Saint Patrick’s.

Douglas and Theresa, then and now.

Not all parishioners have spent a lifetime in the church, but it’s still important to them. Immigrants looking for a reminder of home have found comfort at Saint Patrick’s.

“An old church is actually familiar,” says Beed.

Patricia Odean felt this connection when she moved to Canada from Nigeria.

“When I walked in here, everyone welcomed me like family so it brings me back home,” she says.

Saint Patrick’s draws parishioners from all over the municipality, including those in Fairview, Dartmouth, Sackville and Bedford. It’s because of their patronage that the church has survived, as 90 per cent of the church’s members come from communities other than the North End.

“People are attached to their parishes,” says David Seljak, a religious studies professor at the University of Waterloo. “They (have) formed deep emotional bonds.”

A stiff battle

But the landmark is showing its age.

The church’s bell can no longer be rung due to water seeping into the steeple and bell tower. The area is off limits due to structural damage.

The building’s bricks are a safety risk, says Peter Browne, financial administrator for the Archdiocese of Halifax-Yarmouth. Freezing and thawing of water between the inner and outer brick has caused the two layers to separate. The outer layer of brick has been pushed out and is at risk of falling.

“It is a pretty dicey situation,” Browne says. “We’re literally putting giant screws into the inner and outer facade to keep it together.”

In 2013, chunks of granite fell from the church’s bell tower to the sidewalk. Even now, three years later, heavy pieces still hang overhead.

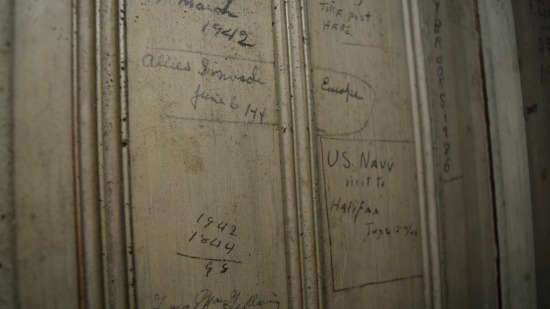

caption

Parishioners marked events like the day the Allies invaded Normandy in 1944 on a door in the bell tower, now an off limits area due to damage

With a dwindling congregation and a lack of priests, the Archdiocese planned to shut down churches and consolidate parishes. An aging Saint Patrick’s was picked for closure.

Aware of its historical and personal importance, parishioners wouldn’t let Saint Patrick’s green wooden doors shut permanently. After convincing the bishop to give the parish a chance, a time limit was set. They were given 30 years to restore the building in order for it to remain open.

The Saint Patrick’s Restoration Society was formed in 2009. Since then, the society has put in three new gas furnaces, fixed the roof and completed emergency repairs on the steeple and bell tower.

From concerts to dinners, the society has spent the last seven years fundraising. It has raised enough money for immediate repairs, but needs more funds to restore the facade of the church, steeple and bell tower.

“There hasn’t been a lot of money generated that has gone into fixing the church,” says Browne, noting that the Archdiocese hasn’t seen many results.

There has been a steady effort, but he says a lot of the money they’ve raised has gone into planning bigger fundraising events.

The society hopes to raise enough money for outside restorations through a capital campaign that will seek support from the Halifax community, heritage groups and all three levels of government.

“We need that support … to help us save an icon,” says Michele O’Neill.

caption

Damage on a wall near the bell tower

Jennifer Watts, former councillor for Peninsula North, the district that includes Saint Patrick’s, says the community cares about the church, but it remains to be seen if they’re ready to put their money behind it.

“I think they have a fairly significant and stiff battle to raise the money to support it,” she says.

Saint Patrick’s is no stranger to the community, as Watts says she has always been impressed by the church’s involvement in the city.

“It’s not just talking about preserving a heritage property,” Watts says. “It’s also about the role and the work of the local church community.”

When Hope Blooms, an organization that engages at-risk youth through gardening and entrepreneurship, needed a home for its first greenhouse, the church gave up its parking lot and provided a water source.

“It was a huge help,” says Alvero Wiggins, Hope Bloom’s program manager.

Wiggins grew up in the North End. He remembers Saint Patrick’s as the first place to have breakfast program for kids. Wiggins says a nun at the church, Sister Cecilia MacNeil, helped bring the breakfast program to local schools.

In 1971, when hungry residents continually knocked on the priest’s door in search of help, the church launched the soup kitchen, Hope Cottage. Parish members still volunteer at Hope Cottage, preparing 16 to 20 meals each year.

Last year, the church helped raise $66,000 for outreach projects with the Catholic organization Saint Vincent de Paul Society.

Beed says this work is fuelled by the synergy of the group gathering at church.

“Your energy comes from getting together,” he says.

Watts says there will be opportunities for Saint Patrick’s to reach out to the municipal government by applying for community grants.

Historically significant structures like Saint Patrick’s are worth preserving, says Peter Ziobrowski, founder and president of The Action Group for Better Architecture in Nova Scotia.

“Some of these big churches, they tell an important story about who we were as a people and how we lived,” he says.

caption

About 200 parishioners fill the pews each SundayDecline in religious attendance

Saint Patrick’s isn’t alone in its struggle.

Churches across Nova Scotia are disappearing as congregations dwindle.

“We are living in a new reality,” says Seljak. “In churches, overall in Canada, you would see attendance in the single digits.”

According to Statistics Canada, in 2011, nearly a quarter of Canadians have no religious identity. The number of people regularly attending religious services has been on the decline since the 1980s, causing some churches to close for good.

The country’s older churches are the inheritance of an era when religious services were well attended. As Canadians move away from the church, small parishes pay a steep price to keep these places running.

“If you go to any rural Catholic church, what you’ll find is the average age will be in the mid-70s and the pews will mostly be deserted,” says Seljak. “How is a population like that going to sustain these very expensive buildings?”

When the weather cools, parishioners at Saint Patrick’s keep their jackets on during mass. Keeping the church at a reasonable temperature costs between $25,000 and $30,000 a year. The heating bill along with insurance costs, property tax, overhead for staffing and snow removal are all up to the parish to pay.

While the church has a capacity of around 400, only about 200 worshippers gather in the timeworn pews on Sundays.

“You’re always nervous when your numbers start going down because that impacts your revenue,” Michele O’Neill says.

caption

Saint Patrick’s has managed to avoid closure so far

Saint Barra’s was more than a place to practise religion, says Marie Higgins, who used to worship there. It was a gathering place for the community housing concerts and Gaelic language lessons.

Higgins is in the process of appealing the closure.

“The church was one of the places where everyone knew we would see each other,” she says.

Now, those who once attended services Saint Barra’s are scattered, spending Sundays at other churches.

“We would like to have our own parish back,” Higgins says.

Beed says a church is a hard thing to give up. He doesn’t want Saint Patrick’s to meet the same fate as Saint Barra’s.

“I don’t think I’m being selfish by saying we have something special to keep,” Beed says.

Parishioners at Saint Patrick’s don’t want to lose their home.

“There’s no certainty,” Michele O’Neill says. “We move forward with faith.”

But they’re determined to do what it takes to keep their church open.

“It’s a great little gem in a box that needs some work,” Beed says.

About the author

Payge Woodard

Payge is a master of journalism student at the University of King's College. She's interned for Bangor Daily News in Maine and freelanced for...

M

Michael Padilla

U

Uli vom Hagen

m

margo grant

K

Kenneth MacInnis

M

Michael Creagen1