Seas rise, Nova Scotia sinks

caption

View from Point Pleasant Park.While Venice sinks, the Dutch strengthen their dikes. The Gulf of Mexico eats a football-field sized piece of Louisiana every hour. Every pocket of the planet can feel the fact that the oceans keep climbing higher.

And climbing faster. The data on record – almost 200 years’ worth, with anecdotal evidence reaching back further – affirms that sea levels have long been rising; but things have accelerated.

Global warming is the commonly accepted culprit. As water gets warmer its molecules spread out, increasing the water’s volume. In a glass of water, the difference is minute; when that glass is big enough to cover more than 70 per cent of the globe, the difference is substantial.

Meanwhile, glaciers both north and south are undergoing their own molecular change – melting, thus adding incalculably large volumes to the planet’s growing oceans.

Halifax’s unhappy fate is to be caught between two inevitabilities.

While the oceans inch upwards, the land itself is sinking.

caption

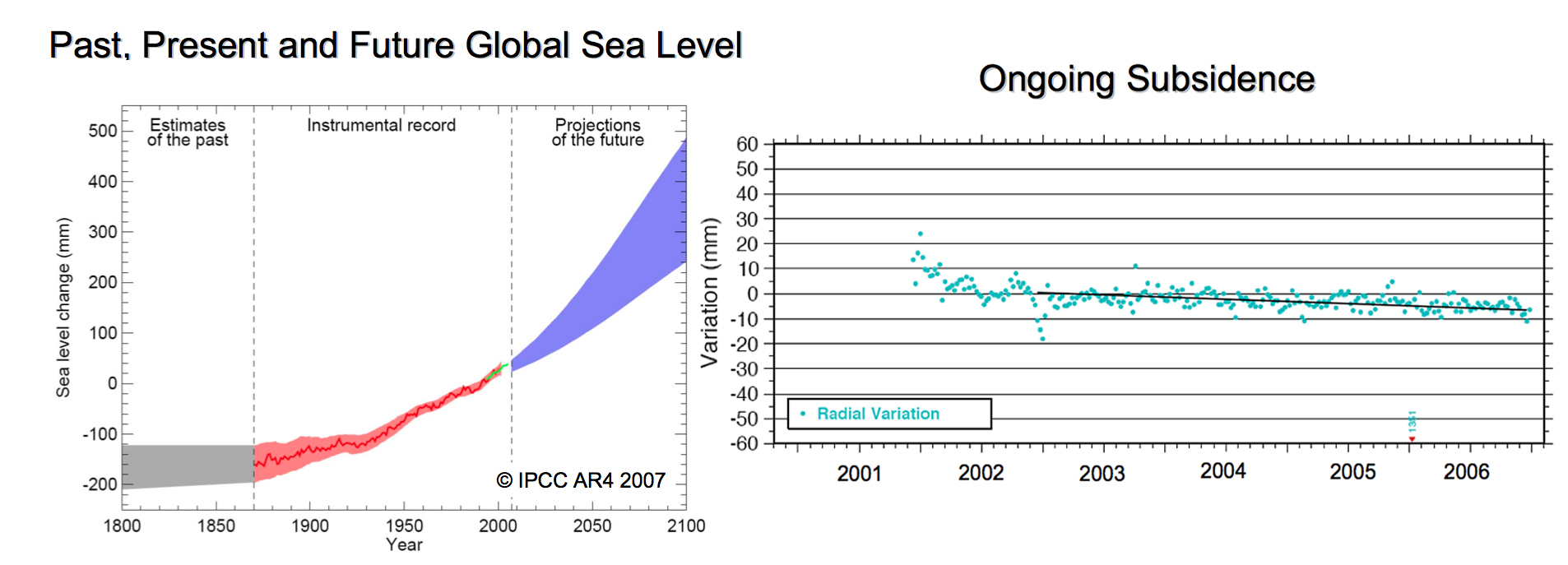

Left: the past, present and future global sea level, according to the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Right: the ongoing subsidence in Halifax. Both charts come from the “Sea Level Rise Adaptation Planning for Halifax Harbour”, presented to Halifax city council in February 2010.“So we get this double whammy, this double impact of sea level rise,” says James Boxall, geography professor and director of the GISciences Centre at Dalhousie University.

“That’s what makes Halifax unique. We actually have a device in the harbour that’s measuring the amount of subsidence every year, so we know that as we sink and the sea rises, you’re getting this multiplier effect.”

Boxall was one of the researchers behind a 2010 report to Halifax city council, which sought to lay a scientific foundation for the city’s coastal planning practices and help it adapt to sea level rise.

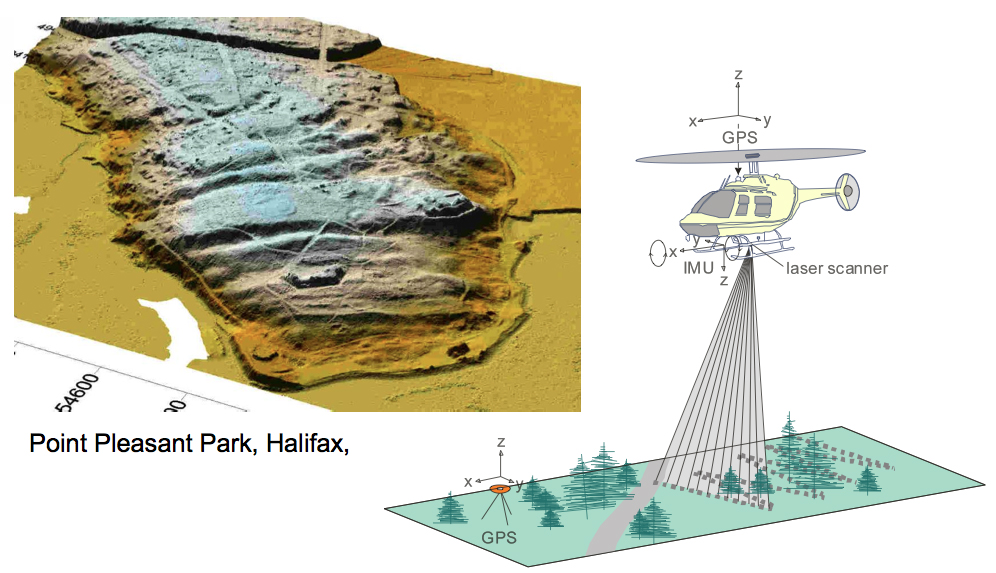

Using LiDAR mapping – a process by which a laser-toting aircraft is used to map terrain in minute detail – they examined the height and shape of the land to identify places most at – risk of flooding in the event of a storm surge.

caption

Left: a detailed map of Point Pleasant Park elevation made with LiDAR mapping technology. Source: “Sea Level Rise Adaptation Planning for Halifax Harbour”.Then they took the latest projections for sea level rise from the UN’s Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change – pegged at 0.57 metres in 2007 – and added the effect of land subsidence, or sinking.

The most likely scenario, researchers found, is that Halifax’s landmass will sink about 16 centimetres in the next hundred years. Combined with the rising waters, they project the sea will be 0.73 metres higher to the shore.

Even with the “double whammy” that figure is likely too small, explains Boxall.

Compared to those of other researchers, the IPCC’s projections are conservative to begin with, but they also don’t take into account the water added by melting glaciers. The enormity of these ice caps and all the variables at play would make such estimates untenable, Boxall says.

Listen to James Boxall:

https://youtu.be/VlhXC8Qy-v8