Reconciliation

Secret Path project to be taught in Nova Scotia schools

Students will start studying residential school story next year

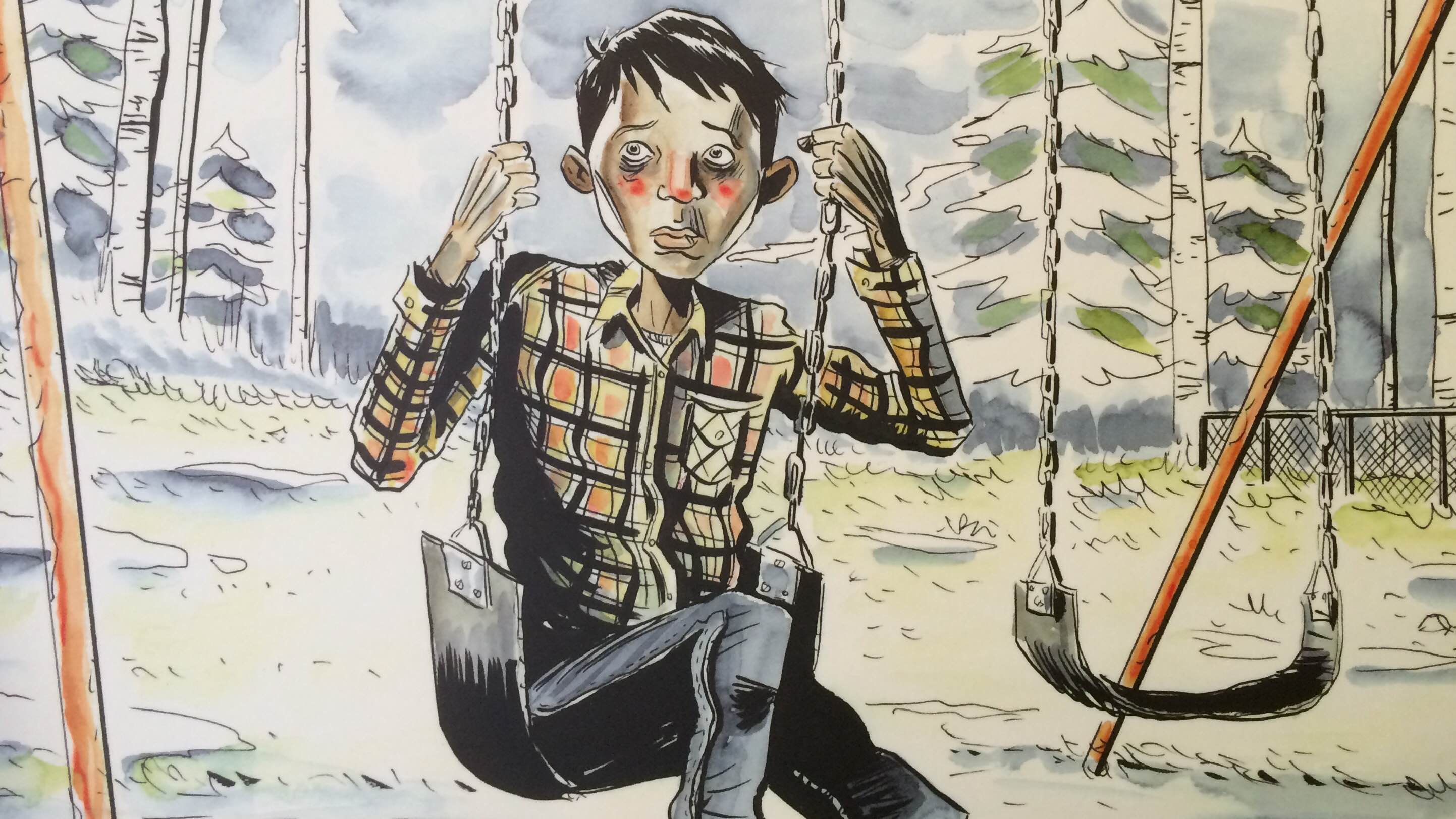

caption

Illustration from the Secret Path project by artist Jeff Lemire.

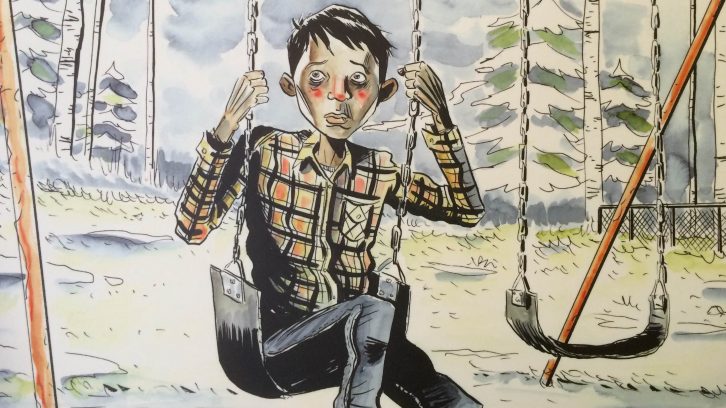

caption

An illustration from the Secret Path project by artist Jeff Lemire.Students in Nova Scotia will learn about the history of residential schools in Canada through the decades-old story of an Ojibway boy who died while running away from one.

Next September, the Secret Path project will be introduced into the province’s education curriculum.

“Secret Path has come along and really been the wedge that opened the door to learning this history in a new way,” said Wyatt White, director of Mi’kmaq services for the Nova Scotia Department of Education and Early Childhood Development. Related stories

Secret Path is a 10-song album by The Tragically Hip’s frontman Gord Downie, a graphic novel by illustrator Jeff Lemire and an animated video. It tells the story of Chanie Wenjack, who was only 12 years old when he died after escaping from his Ontario residential school in 1966. He was trying to walk 400 miles back home.

White is overseeing the project’s introduction into Nova Scotia classrooms. He was one of 33 educators from across the country who attended an October meeting in Ottawa to discuss how Secret Path can be used in schools. The Wenjack family, Gord Downie’s brother Mike, and Jeff Lemire were also at the meeting.

Using the musical, visual and written parts of Secret Path mean students will be able to study the project in different classes, like music, art and English.

Currently, students only learn about residential schools in junior high social studies courses, some Canadian history courses and an optional high school Mi’kmaq studies course.

A difficult subject

Wenjack died 50 years ago in Ontario, but his story resonates far and wide in Canada today.

“This story is a gateway for students to learn about the residential school history in their own area, not just the one told in the story,” said White. “Secret Path has created an opportunity for educators across the country to find out who the Chanie Wenjacks are in our own provinces.”

About 150,000 Indigenous children were taken from their families and placed in residential schools from the 1880s until 1996. More than 6,000 children died at the schools and survivors have reported physical, sexual and psychological abuse.

White said some teachers have already started using Secret Path in their classrooms. Others can expect to receive professional development materials related to the project before next September.

“We’re sensitive to the fact that this is not a simple or easy area for teachers to take on, especially if they’re not as familiar with the subject matter,” said White. “We want to make sure they have enough support to be able to use it in their classrooms well.”

Students will start studying Secret Path in full in Grade 7, but some parts of the project may be used at the elementary level to introduce younger students to the subject.

“We’re working to determine the foundation kids need to have in place about the Mi’kmaq community and Indigenous people in Canada, so when the topic of residential schools comes up, they’re emotionally ready to learn about it,” said White.

Spencer Wilmot is the director of education with the Native Council of Nova Scotia. Wilmot is not involved with bringing the Secret Path project into schools, but he thinks Grade 7 is a good time to start teaching this part of history.

“I think the sooner students understand what Aboriginal people went through with the residential school system, the better,” he said. “Our own Aboriginal students need to know their past as well.”

Treaty education

Last year, the Truth and Reconciliation Commission called on the federal government to “draft new Aboriginal education legislation with the full participation and informed consent of Aboriginal peoples.”

The release of the Secret Path project comes as the Nova Scotia Department of Education and Early Childhood Development is completing its framework for treaty education in the public school curriculum.

“The framework will infuse aspects of treaty education in every single grade in every single subject,” said White. “It’s a guiding structure to ensure there are opportunities for every student to learn about Mi’kmaq history, culture and values.”

The curriculum framework is structured around four questions: Who are the Mi’kmaq? What are the treaties? What happened to the relationship? What are we doing towards reconciliation?

“It will teach a more balanced perspective on history and the fact that Canada is based on the treaty relationship that exists in each of the provinces,” said White.

The Nova Scotia Department of Education also gave every school in the province a hand drum made by a Mi’kmaq this year. Elementary music teachers received traditional drumming instruction and learned the Mi’kmaq Honour Song and cultural significance of drumming to Mi’kmaq culture.

Wilmot thinks these kinds of structural changes are a good start for reconciliation in Nova Scotia.

“When I went through the public school system quite a while ago, we were made to feel ashamed of our culture,” said Wilmot.

“Mi’kmaq students should feel proud of their heritage, and right now they don’t get that in textbooks. The more the curriculum addresses that, the better it will be.”