Science

Water is becoming ‘a geopolitical issue’: expert

Lecture given at Museum of Natural History puts focus on changes in water levels and what it means for the future

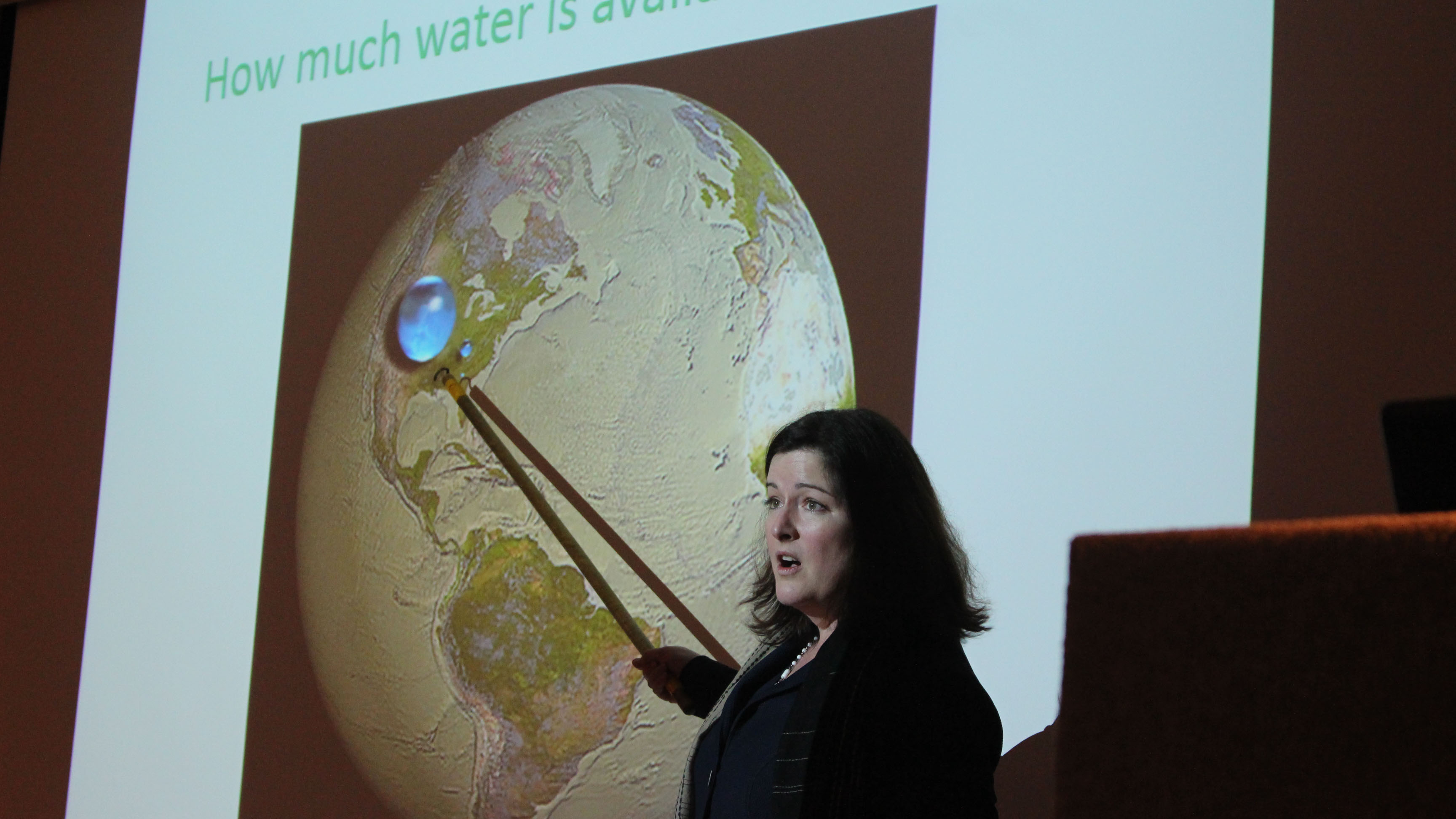

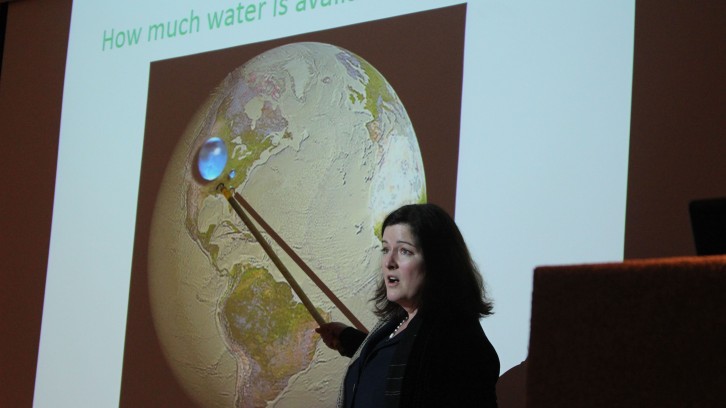

caption

caption

Shannon Sterling’s lecture highlighted the strain mankind puts on our water resources by irrigating unsustainable farmland.Water’s scarce. And it’s getting scarcer.

That was the message given by hydrologist Shannon Sterling at a lecture held at the Museum of Natural History Monday. The topic was the effect of human development and climate change on our global water levels and cycles.

Sterling said we’ve entered a period of water redistribution, where dry areas will become drier while others will become more wet. Driving this change and shortage of water is deforestation and urbanization that leads to loss of valuable soil.

“Without plants, without soil, the rainwater will just go down, become runoff and not stay in the system. The key is to preserve our soil and appreciate its value to our ecosystem,” she said. “To create this soil is hard. It’s up there with desalinating sea water. It takes thousands of years to create it.”

Depleting our current water stores will also create problems down the road. Agriculture is a culprit, said Sterling, especially when water is used irresponsibly for irrigation in what are already dry areas.

“We need to decide if it’s really worth keeping up the agriculture where it is,” Sterling says.

The short of it, she said, is there will be a change in where water is found. And in regions currently suffering, the water shortage will only get worse.

“The dry areas and the tropics will be affected the most. Semi-dry areas like Kenya that have fragile ecosystems. They suffer through droughts and those will get worse,” says Sterling. “In wetter areas, we will see more floods, but that we can plan around.”

The global changes will lead to greater food insecurity, as droughts will kill off crops. Urbanized areas will likely see inland flooding. Above all, the uneven distribution of water will force us to reconsider the places we live.

“Those who have water will have more. Those that don’t will have less. It’s more of a geopolitical issue centered on putting people where the water is,” she said. “Putting the agriculture where the water is. It’s a matter of changing the way we think about cities.”

Here at home, the Prairies and the glaciers in British Columbia are drying up. And while Nova Scotia won’t have a water shortage, Sterling says a plan is needed.

Sterling is the head of the Hydrology Research Group at Dalhousie University. In 2014, they released the first Watershed Atlas of Nova Scotia. She said the first step for Nova Scotia is to understand where our water is going and assess the risks.

“It hasn’t been done yet, but the Department of the Environment is starting to do that. That’s the first step,” she said.

About the author

Mikkel Frederiksen

Mikkel is finishing his Master of Journalism at the University of King's College. He's fond of watching films, and sometimes writes about them...