Covering Killers

caption

Research shows that in-depth coverage of killers has the potential to inspire copycats.How should news media respond to mass shootings?

To make a point during his lectures, Dr. Pete Blair shows two photos to his criminology students at Texas State University.

The first is a picture of Victoria Soto. On December 14, 2012, Soto gave her life trying to protect her first-grade students from a deadly shooter at Sandy Hook Elementary School in Newtown, CT.

“Do any of you know who this is?,” Blair asks, pointing up at the fallen hero.

The students look puzzled. One, maybe two people in the entire lecture hall raise their hands.

caption

The deadliest mass shootings in both Canada and the U.S. occurred on university campuses.Blair then switches to a photo of Adam Lanza, the man behind the massacre at Sandy Hook. Armed with a Bushmaster XM15 assault rifle, 20 year-old Lanza opened fire in the school. He killed 27 people before turning the gun on himself. Twenty of the victims were children. It remains the second-deadliest one-man shooting spree in U.S. history, behind Virginia Tech in 2007.

Blair then asks the students the exact same question, with Lanza staring down at them from the screen above.

“What about this guy. Do you recognize him?”

More than half the audience gingerly raise their hands.

Lanza’s picture made national headlines. Just four days after the shooting, even the BBC published a profile of him. Soto’s heroism was praised in the media, but it was the villain’s face that stuck.

For Blair, this is a troubling reality.

“What does that say about us?,” said Blair. “What does that say about how we’re treating these things? What does that say about the lessons we’re learning from these events?”

The copycat effect

“Active shooter” cases, such as the Sandy Hook tragedy, receive significant media attention in Canada and the U.S. According to a U.S. Department of Homeland Security definition, “active shooters” aim to kill multiple people in a confined, populated area. The victims are selected spontaneously, distinguishing active shootings from gang violence and other homicides.

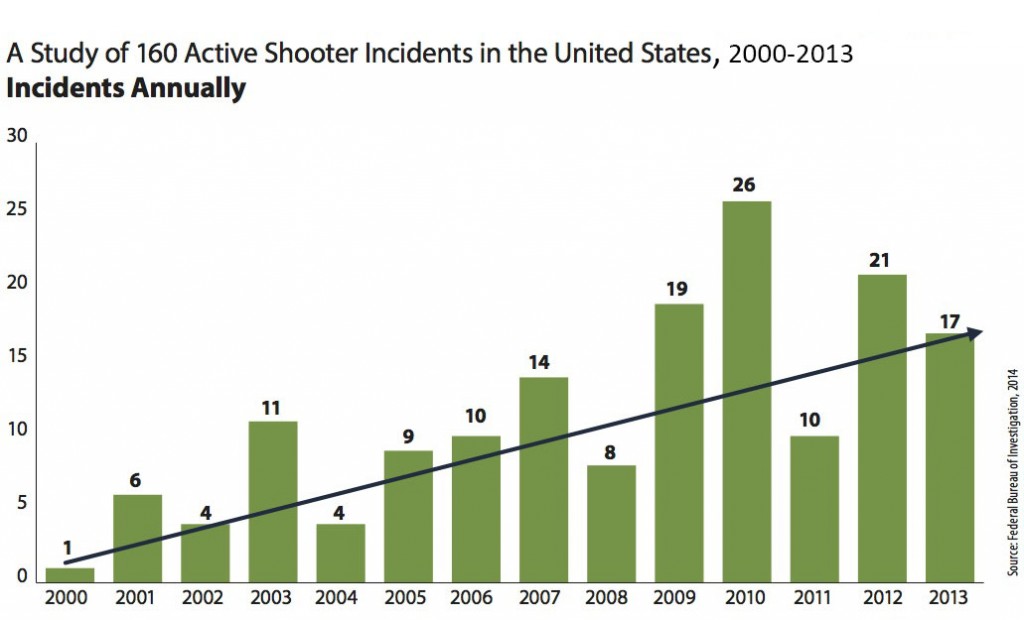

While violent crime rates in both Canada and the U.S. are declining, an FBI study says active shooter incidents are on the rise. From 2000 to 2007, there were an average of 6.4 shootings annually in the U.S. Since 2007, it has jumped to 16.4.

caption

Source: FBI, 2014.North of the border, gun violence is rare. Since 1966, there have been 16 incidents in Canada that match the active shooter criteria. The last two – The Moncton RCMP shooting and the attack on Parliament Hill – occurred just four months apart in 2014.

So what does this all mean? Blair has an idea.

Aside from his teaching duties, Blair is an FBI analyst. He was a primary researcher for the active shooter study. Based on his findings, Blair believes the rise in mass shootings has a lot to do with how killers are portrayed in the news.

“We’re definitely concerned about the copycat effect,” said Blair. “The one thing we do see consistently in a lot of these shooters is that they’ve done research on previous shooters. They’re looking at them as models for how to be successful in their attack.”

According to Blair, the news media provides these models by giving in-depth coverage of killers. He says these news reports have the potential to inspire others crippled by the same demons.

Blair says journalists need to change their approach.

“I’m not saying you shouldn’t cover these tragedies,” said Blair. “Just switch the focus from this monster to the person who’s a hero.”

Zeynep Tufekci, an assistant professor at the University of North Carolina, shares Blair’s opinion. She says the media should omit the killer’s name completely from mass murder coverage.

“It is the fame and notoriety that motivates them,” said Tufekci. “Sensational news coverage gives them that recognition. We must take it away.”

Both Tufekci and Blair believe journalists need to cover mass murder with the same guidelines often used to cover suicide. They say the media shouldn’t release names or methods, and that reporters should hesitate to approach traumatized survivors or families.

“News organizations eventually figured out that reporting these sensational suicides ultimately caused public harm,” said Blair. “I would argue for a similar approach to mass murderers. The standards can change, it’s just a matter of recognizing that there is no public value in focusing on the killer.”

Dr. Ray Surette, a criminology professor at the University of Central Florida, says “these stories are appealing for the same reason we like rollercoasters and horror movies. There’s a real fascination.”

But Tufekci just doesn’t see it that way.

“Maybe they would be newsworthy, if they weren’t all the same,” said Tufekci. “They all paint the same basic picture: damaged, loner guys with psychological issues. It’s a clear profile, so who cares?”

The ‘Don’t Name Them’ campaign

Blair’s research captured the attention of the local FBI in San Antonio. In July, Blair and a team of like-minded students joined forces with the FBI to spread their message and discourage the media from naming killers. The alliance is called the “Don’t Name Them” campaign.

Special Agent Michelle Lee speaks on behalf of San Antonio FBI when warning the media about glorifying killers in coverage of mass murder.

“At San Antonio FBI, we believe it is in the public’s best interest that the news media does not cover shooting events in a way that glamourizes the shooters,” said Lee. “There is a strong case for withholding their names.”

With selective, more considerate coverage, Blair believes journalists can help prevent future shootings. That being said, the news media still has an obligation to report the whole truth.

So, are Blair’s suggestions feasible?

Dr. Pete Blair explains the reasons for the Don’t Name Them campaign

Part of the story

Justin Bourque terrorized Moncton, N.B. starting on June 4, 2014. Armed with an assault rifle, a shotgun and a crossbow, Bourque gunned down three RCMP officers before surrendering after a 30-hour manhunt.

Kathryn Blaze Carlson was on the ground in Moncton reporting for the Globe and Mail. For two weeks after her arrival on June 5, Carlson’s job was to tell the story. She wrote about the community, the fallen officers, and Bourque himself. She had no issues with digging into the man behind the carnage.

“I can’t imagine most newspapers or reputable news organizations going ahead with a policy where they don’t name a killer,” said Carlson.

Only the Sun News Network adopted such a policy. In line with Blair’s principles, Bourque’s name and photos were omitted from Sun’s TV broadcasts. To a Globe reporter like Carlson, this is “bizarre.”

Carlson believes in-depth coverage of a killer has significant explanatory value. She says to exclude it and report the whole story effectively is impossible. This is why she staked out Bourque’s family home and questioned his known associates.

Without Bourque’s story, she says, her coverage would have been incomplete.

“There’s something to be said for understanding the family, the community where he grew up, and the environment he was in when he decided he had to go out and kill cops,” said Carlson. “It’s not just to satisfy the curiosity or more sensational appetites that readers might have. I think it’s just part of the story. The victims are part of the story, the city is part of the story, the killer is part of the story.”

Carlson says covering killers is part of the news media’s responsibility to tell the truth.

“We have a responsibility to cover the murderer,” said Carlson. “We have a responsibility to understand who that person is and what sparked him or her to become so violent.”

Tamsin McMahon, an associate editor and writer at Maclean’s, published a cover story, The untold story of Justin Bourque, just 11 days after the shooting. She says her article answered important questions that readers wanted to know.

“Who is he? What was his motivation? How did he carry this off? How did he evade police for so long? These are important questions that need to be answered so we can prevent tragedies like this in the future,” said McMahon.

As for the copycat effect, Carlson and McMahon don’t think it’s enough to justify a shift in reporting standards.

“I guess I don’t view reporting a story as giving someone their 15 minutes of fame,” said Carlson. “I don’t view revealing to Canadians, and to the community that he deeply affected, who the person is that wronged them as sensationalism.”

Carlson said covering mass murder properly requires balance and sensitivity. Examine the killer, but tell the victim’s story as well.

While looking into Bourque, Carlson felt “just as obligated” to tell the stories of the fallen officers. This is reflected in her coverage.

Carlson insists her reporting in Moncton was “sensitive and responsible,” and she encourages other journalists to do the same.

A public service

Serge Kovaleski is a veteran crime reporter with the New York Times. Following a 2012 killing spree in Aurora, Col. that left 12 dead, Kovaleski and three colleagues spent six weeks writing a profile of the shooter, James Holmes.

The story is an intimate examination of Holmes’ life. Kovaleski and his co-writers paint the picture of a deeply troubled man who, in his last moments of freedom, was reaching out for help.

Kovaleski believes this type of coverage is a necessary public service.

“One reason we cover mass murders the way we do is because there’s a real, practical public service that can come out of these stories,” said Kovaleski.

He recalled that his sources for the Holmes profile saw value in getting the killer’s story out there. He said they “wanted to help.”

“The more that we can lay out who these people were and what they were struggling with, the more people can learn from this,” he said.

By examining the darkness of one man, Kovaleski said, we can more easily identify it in others. Like Blair at Texas State, Kovaleski wants to prevent future shootings. But their ideas about how to achieve this are very different.

“By laying out these rather intimate portraits of people like James Holmes, we better understand these kinds of people and hopefully we’re in a better, more powerful position to perhaps identify them when they cross our path,” said Kovaleski. “It all goes towards a public service in educating people and ultimately preventing these shootings.”

At the heart of all good stories are people. For Kovaleski, mass murder coverage is no different.

“It’s not the violence we’re so much interested in,” said Kovaleski. “But the person, and what drove them to do what they did.”

“Just doing our jobs”

All news reporters are driven to fulfill the same goal: report the truth, as fully as possible.

For Kovaleski and Carlson, this means covering every angle. Readers will always need to know who, why and how. In defense of thorough journalism, they say, this applies to murderers too.

“We are just doing our jobs,” said Carlson.

Kovaleski can’t imagine mass murder reporting done any other way.

“These critics don’t offer any alternatives other than ‘don’t name them, don’t write about them’,” said Kovaleski. “That is just not feasible.”

Despite Blair’s arguments, Kovaleski insists the tell-all strategy when covering mass murder is effective and ethical.

“First of all, we don’t sensationalize anything,” said Kovaleski. “What we do is blanket the coverage. We put people on the community angle, the victim angle, and the killer angle. We tell the whole story. It’s all part of thorough, responsible, public-service journalism.”

So the debate continues. To Kovaleski, shooter profiles are “the most important facet of mass murder reporting.” Blair writes off their value, simply saying, “there is none.”

If Kovaleski’s standpoint is reflective of how the mainstream news media will respond to the next mass shooting, then the future looks challenging for Blair and the “Don’t Name Them” campaign.

“To use the words of these critics, ‘glorifying’ these guys is not what we do,” said Kovaleski. “If that’s a by-product in someone’s eyes, so be it.”

Active Shootings in Canada, 1966-2014

Editor's Note

This story was reported and written by Oct. 17, 2014.