A drive too far

If you're a victim of sexual assault in Atlantic Canada, where you live may decide what help you get.

Editor's Note

This story contains graphic details of sexual assaults that may upset some readers. Interviews and factual information current as of May 4, 2017.

Sitting in a hotel room with two older men, Courtney Dunne tried to keep their hands off her body.

“I would take one of their hands off and the other one would continue where the first one left off,” Dunne recalled.

“Then I knew that I wasn’t going to get out of it. It was two big guys and I was a very small 16-year-old.”

When they took her to the bathroom, Dunne hid by the toilet as they tried to tear off her dress. The men picked her up, threw her in the shower and raped her.

“One of them was holding me and the other one was raping me and then they’d turn me around and switch.”

The next day, Dunne went to the mall with a male friend. When he playfully tried to tickle her, she began to cry, then told him what happened.

She had blamed herself thinking she didn’t say “no” enough.

But her friend was blunt; “Courtney, that was rape.”

She went to the police.

Because she had reported the assault within five days, Dunne was able to have a forensic examination. Specially trained nurses assessed her injuries, looked for DNA evidence and told her about follow-up care options.

“The two nurses I had were very supportive and understanding,” Dunne remembered in an interview five years after the assault.

Specially trained nurses

Sexual assault nurse examiners, as they are called, hear lots of stories like Dunne’s. Sometimes they are told through tears or hysterical laughter, or barely uttered by those who aren’t ready to speak.

“There’s lots of … things that have happened that I definitely won’t forget,” said Ann Marie Provencher, a sexual assault nurse in Newfoundland.

“You’re helping someone at the worst possible moment in their life.”

But not everyone in Atlantic Canada gets the same care. Where someone is attacked makes a difference.

Patchy sexual assault nurse examiner programs mean some victims are cared for by two of the specially trained nurses, while services for others are inconsistent or don’t exist. Large pockets of New Brunswick, Nova Scotia and Newfoundland and Labrador are without proper services, and Prince Edward Island has no program at all.

Lack of training means physicians and nurses throughout the region may be uncomfortable gathering evidence, or may be unaware of problems that exist with the main tool used to do that, something called a rape kit. The kits provided by the RCMP are out of date and contain instructions to employ traumatizing procedures, such as gathering pubic hairs, that are no longer considered necessary.

| Sexual assaults reported to police, 2011-2015 | |

| Province | |

| New Brunswick | 2,377 |

| Nfld and Labrador | 1,678 |

| Nova Scotia | 3,273 |

| PEI | 365 |

| Source: Statistics Canada |

Without proper services, victims may have to drive themselves to a hospital that offers better services, or wait for a busy emergency department doctor or travelling nurse.

It’s a wait that Margaret Mauger, the executive director and a counsellor at the Colchester Sexual Assault Centre in Nova Scotia, said extends the emotional trauma that occurs after an assault.

“They are advised not to bath or shower, to keep the clothes, to try not to use the washroom or do so as little as possible,” she said.

“Most people that I’ve talked to want to go home, take a shower and forget about it.”

‘As soon as they follow the instructions to a T, they’ve kind of gone wrong’

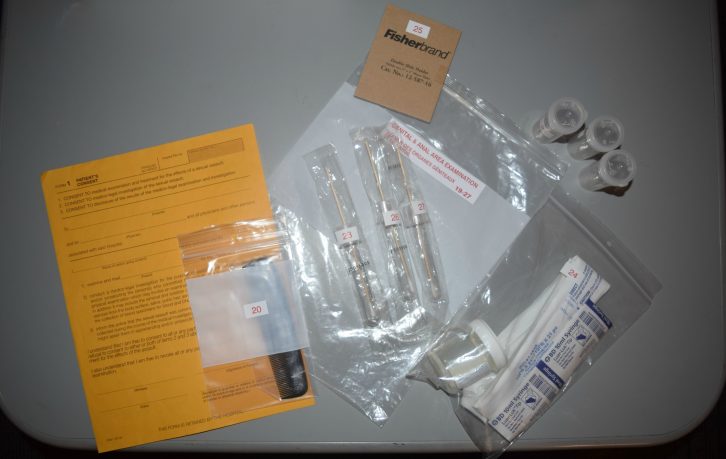

caption

Evidence collection tools and consent form from Halifax’s rape kitThat’s not how it went for Dunne. After becoming weak as the men raped her in the bathroom, they moved her to the bed where they ejaculated on her chest and stomach.

“Then they put me back in the shower and scrubbed me down.”

Dunne feels they were trying to get rid of evidence of the assault.

“They knew what they were doing.”

After a sexual assault, DNA evidence may be left behind. Victims who report to hospitals have the option to have forensic evidence collected using a rape kit. The length of the forensic exam depends on the number of injuries, type of assault and how much time the victim needs. The exam includes assessing injuries, taking photos and swabbing for DNA left behind from an attacker.

“After being violated, you have to let someone see all of you and that’s scary,” Dunne said.

“But I am very glad that I got it done.”

In areas without a coordinated program, police need to be involved as hospitals likely don’t have the right kind of freezer to store evidence.

“The only patients who would have evidence collected would be patients who are reporting to the police,” said the coordinator of St. John’s program, Cynthia MacKey. This is the procedure for all of the Atlantic provinces.

Even for those willing to report to the police, their local hospital might not be much help.

Campaigning for better services

Last year, Christa Mindrum, a family physician in Kentville N.S., headed a campaign aimed at bringing better services to the town.

Local health-care workers felt their rape-kit skills weren’t up to date. The last time Dr. Mindrum had done one of the forensic exams was 12 years earlier during her residency, a learning opportunity that doesn’t come up for all physicians, she said.

After a session to learn more about the kits led by Susan Wilson, the coordinator of Halifax’s sexual assault nurse examiner program, Dr. Mindrum said the health workers were outraged.

“We realized how poorly our area was responding to sexualized trauma.”

Hospital staff had been plucking pubic and scalp hair from patients, not knowing it was no longer considered necessary.

“We’d been doing that all along, thinking we’re just doing what we’re told, that we’re doing the right thing. We didn’t want to skip a step and then they say this kit is invalid,” Dr. Mindrum recalled.

Added Wilson, “Collecting 80 to 100 scalp hairs two to three at a time and 30 pubic hairs, two to three at a time is unnecessary and re-victimizing.”

This isn’t the only issue in the kit provided by the RCMP.

While some sexual assault programs, such as the one in Halifax, use their own kit, the RCMP kit is still used throughout much of Canada. Developed in the 1980s, it includes out of date swabs and a lancet –a tiny needle used to prick the finger for a blood sample–that usually doesn’t work.

The RCMP have been working to update the kit. A new version of the evidence collection tool was supposed to be available in 2008 but many detachments still don’t have it today.

An emotional exam

In Kentville, Wilson’s training session made health-care workers aware of issues with the kits. But even with the training, Dr. Mindrum feels a regular physician isn’t the best person for this job. She said the forensic aspects of the exam are out of the realm of what physicians are trained to do.

“We know that if they want to use this evidence in court, they are better off to use somebody who truly is an expert in doing it, not somebody who is reading steps of a kit,” she said. “Because we have an MD behind our name, (people think) we’re somehow qualified to do it.”

Dr. Mindrum said physicians in Kentville have said the best thing they could do for patients is drive them to another hospital, such as one of the four facilities served by Halifax’s program where she said care is top notch.

While doctors in Kentville do their best to step in for sexual assault nurses, not every hospital has the time to help.

“It’s not just collecting a few swabs and it’s done,” said Wilson. “It’s a medical, forensic,

emotional exam.”

In Alberton, P.E.I., Western Hospital’s one emergency doctor can’t always take the time to do the exam. If another patient walks in, the doctor may need to step away to help. Bev Ashley, the clinical lead of the emergency room, said that isn’t acceptable when working with a rape kit.

“You don’t want to be starting and stopping that, for the patient’s sake,” Ashley said.

Patients turned away from Western have to travel nearly an hour to Summerside.

Dunne feels everyone should have access to the same services she had after she was assaulted.

“You should never be denied the right to a rape kit because that could be the evidence you need for a conviction,” said Dunne.

caption

Services across Atlantic Canada

Across Atlantic Canada, the services a victim receives during that frightening time differ from province to province and even from town to town.

Nine New Brunswick hospitals currently have sexual assault nurse examiner programs.

Roxanne Paquette, coordinator of the provincial program, said two more hospitals will have the service this spring and they will begin to look at more remote areas shortly. Paquette said she has to wait for Horizon Health Network to move forward. Horizon is one of two health districts in the province.

The chair of the emergency network in New Brunswick, Nicole Tupper, said Horizon Health is figuring out where programs will work because the nurses need to work a certain number of hours to remain certified. Tupper said a program will be coming to Upper River Valley Hospital in the fall.

In the meantime, many outside of the program’s reach need to travel to get specialized care.

For those living in more remote areas such as Grand Manan Island in the Bay of Fundy, travelling to another hospital isn’t easy. With no staff trained to work with the kits, Grand Manan Hospital doesn’t offer the service. To have a rape kit examination done, victims need to make the ferry crossing to Black’s Harbour, which takes 90 minutes. The ferry runs only four times a day in the winter–seven on most days in the summer–and the last ferry leaves at 7:15 p.m.

“It’s not very often we see those types of things, but when it does happen, you want to be able to do what you can for your patient,” said Taylor Pothier, a nurse at the island’s hospital. She believes the hospital should have a nurse who can offer the patient the option of having the rape kit examination done there.

Paquette, the provincial coordinator, said in the future it would be best to have a nurse on Grand Manan or have one travel to the island. But she said there has been no discussion about how a potential program would work.

Running smoothly, but not everywhere

In Nova Scotia, there are two programs, in Halifax and Antigonish.

The coordinators of both programs say sexual assault care services are running smoothly, but Susan Wilson, Halifax’s coordinator, said that isn’t the case throughout Nova Scotia.

“In other areas of the province where there are no sexual assault nurse examiner programs, it’s a little bit more patchy.”

caption

Susan WilsonIf victims show up at a hospital without specialized services, they may have to travel to another facility. Getting there is up to the patient but whether they are sent depends on distance and the mental and physical state of the victim, said the Nova Scotia Health Authority’s vice-president, Lindsay Peach.

“The burden of transportation is shared between the client and the sexual assault nurse examiner program,” Peach said.

For those living further from a formal program, RCMP provide the kit and regular physicians and nurses complete the exam. Wilson said wait times can be an issue in these situations. Victims may have to spend time sitting in an emergency department’s waiting room until a doctor is free to do the exam.

“Quite often when that happens, victims will leave and don’t come back,” said Wilson.

Money can help

In 2015, the province allocated $700,000 per year to expand sexual assault services. A new program will be run by Yarmouth’s Tri-County Women’s Centre later this year. The other program will begin in Cape Breton, headed by Sydney’s Every Woman’s Centre.

Bernadette MacDonald, executive director of the Tri-County Women’s Centre, said while the money is a start, it’s not enough.

MacDonald is helping develop the new program that will respond to patients in western Nova Scotia. She said the program may need to begin with one nurse on call in the Tri-County area, then expand with one nurse on call in the Valley and another on the South Shore.

Peach said when the expansion was announced, the health authority issued a request for proposals. The Tri-County Women’s Centre was one of the winning bidders and given a budget to work with.

Trying to work with the money they have available, the Tri-County Women’s Centre submitted a proposal that would see one nurse in each of the three areas it will oversee. But nurses have already put up a red flag on the program, MacDonald said.

A nurse stationed in Digby County may need to travel more than two hours to perform an exam in Shelburne County.

“That distance is too much for them,” MacDonald said.

This is because the examination is conducted by two nurses who support each other in traumatizing situations, take care of different aspects of the exam and sign off that the evidence in the kit is factual. Getting both nurses to the same hospital could be a challenge.

A nurse stationed in Digby county may be called to Shelburne County to conduct an exam,

“The geography is just too great,” MacDonald said. “We need two nurses in each of these three areas.”

The current goal for a response time is an hour and a half. Both MacDonald and the program’s coordinator, Valarie Cormier, hopes services can be improved but agree more funding is needed.

The Nova Scotia Health Authority has no plans to provide more funding, Peach said.

Innovative program cut

The expanding program in western Nova Scotia will also mean a cut to the current services a sexual assault team provides on the South Shore. Residents in the area were tired of waiting for a program, so they established sexual assault services in Queens and Lunenburg counties. The program ensured a mental-health counsellor would come in when a victim of sexual assault arrived at the hospital. When the new sexual assault nurse examiner program arrives later this year, that service will be cut.

“We’re the only place that has it at the moment. The rest of the province doesn’t so they’re trying to make the whole province the same,” said the coordinator of the current services in South Shore, Donna Crouse.

“Instead of adding it to everyone else, they’re taking it from us.”

In Kentville and surrounding areas covered by the new western program, physician Dr. Mindrum said it will be a hybrid system with emergency staff acting as assistants.

In Colchester County, the director of the sexual assault centre, Margaret Mauge, said victims who want a rape kit examination done have to travel to reach services. She said every Nova Scotia community was hopeful they would get a chunk of the $700,000.

In Newfoundland and Labrador, only one hospital offers the specialized service. Cynthia MacKey, coordinator of the program, said an ambulance will bring patients from outside St. John’s to the service but she feels that prolongs the traumatic experience.

The limited coverage leaves some communities more than eleven hours from services.

MacKey doesn’t feel the system is fair.

“I believe regardless of where you live in the province, everybody should have equal access to the same services, which we don’t have right now,” she said.

MacKey said besides better care, there’s another important advantage to having a formal program.

Time to consider options

“We have the ability to store evidence for patients who are not reporting to the police, which gives them to opportunity to go home, think about it, (and) make up their mind.”

The Newfoundland program holds the kits for a year. Evidence must be stored in a special locked freezer that a hospital may not have. MacKey said this means victims who aren’t ready to report the crime won’t have the option to have a rape kit examination because the RCMP supply and store kits in areas without formal programs.

“They could come in and not have their mind made up and then no one would collect any evidence,” said MacKey.

Last year, three or four patients cared for by the St. John’s program waited before deciding to press charges. When they were ready, the kit was forwarded to the police.

New Brunswick and Nova Scotia’s programs keep kits for six months.

Wilson, Halifax’s coordinator, said patients usually decide whether they want to report an assault to police within that time. The program also needs to create room for new kits.

“There’s one of our sites that’s a very, very busy site and we’re purging evidence from there quite regularly just to make space because (the fridge is) often full or close to full,” said Wilson, the program’s coordinator.

In Prince Edward Island, there is no option to store evidence as the province currently doesn’t have any formal program. According to Health PEI’s Amanda Hamel, however, the province does have some hospital staff trained who took either a four-hour or two-day course on caring for sexual assault victims.

As she waits for better services in Nova Scotia, Kentville family physician Dr. Mindrum’s thoughts on inconsistent services ring true for all Atlantic provinces.

“You can show up in every ER in Nova Scotia and be treated adequately if you’re having a

heart attack. It’s ridiculous to think that something like sexualized violence, which is an absolute legitimate reason to show up in an emergency room, wouldn’t receive the same standardized care,” she said.

Important evidence

Sexual assault programs impact on the justice system

The evidence collected by a sexual assault nurse, including the DNA swabs, photographs and documentation of injuries may be used if a victim chooses to press charges.

A report funded by the Department of Justice Canada’s Victim’s Fund looked at the effectiveness of the sexual assault nurse examiner program run by the Avalon Sexual Assault Centre in Halifax and found the services provided by the nurses helped investigations because victims are less traumatized after receiving the expert level of care.

Despite low conviction rates for all sexual assault cases, cases Avalon’s program worked on that went to court resulted in more incarcerations and longer sentences than other cases.

caption

Graphic by Payge WoodardEvidence from the kit can assist a case, but it may not be the only thing that goes to court. A sexual assault nurse can be called to testify as an expert witness.

Halifax senior crown attorney, Jennifer MacLellan, has worked on cases where sexual assault nurses have testified and said the health care workers bring an important voice to the courtroom.

“In a sexual assault case, you tend to have only the evidence of the person who is the victim,” MacLellan said.

“Sometimes you don’t even have that. All you have is circumstantial evidence because for some reason, maybe due to intoxication or something else, the victim can’t recall what happened.” MacLellan points to the recent case in Halifax, in which a taxi driver was accused of assaulting an intoxicated woman who had no memory of the incident.

MacLellan said the nurses can explain any injuries the accuser had at the time of the examination.

“You have direct evidence from a completely independent person and that’s incredibly helpful to the prosecution of such cases,” said MacLellan.

Paramedic convicted

Nurses from the Avalon Centre aided MacLellan in a 2014 case against Nova Scotia paramedic James Duncan Keats that received national publicity. Court documents state Keats was charged with sexually assaulting an elderly woman, during a medical call. He had been fired from his job as a paramedic in 2013, after a number of sexual assault allegations surfaced.

Despite suffering from angina, needing a double knee replacement and going blind in one eye, the woman was the primary caregiver for her husband and mother.

When her husband fell and she couldn’t help him up, the victim used her Lifeline medical alert system to call for help. Keats was one of two responding paramedics.

After she experienced chest and angina pain during the call, Keats took her upstairs. He told her to lie on the bed. According to court documents, she testified that after unzipping her night dress, Keats lifted her breast to use his stethoscope. The woman went on to say the paramedic probed her abdomen then pulled her underwear down to her ankles.

Keats put his hand on her vagina then his fingers inside.

“Don’t do that. I don’t want you to touch me,” she recalled telling the paramedic, according to court documents.

She remembered, “Oh, but you’re going to feel so much better,” was his reply.

After continuing to assault her, Keats eventually began to have intercourse with her, telling her he was going to make her feel better.

“Please don’t do this. I haven’t had intercourse in 16 years. You’re going to hurt me,” she told the court was her reply.

The victim was examined by Avalon sexual assault nurse Paula Nickerson. Nickerson found, documented and photographed an abrasion to the posterior fourchette, the thin tissue area of the vaginal opening, a common injury suffered during a sexual assault. Nickerson told the court friction caused the injury, and the judge rejected defence arguments those injuries could have been caused by something else.

Susan Wilson, the program’s coordinator did not examine the woman but told the court it was one of the largest injuries she’d seen to the area. The injury was key to the judge’s decision to convict.

MacLellan said the case is a great example of how a sexual assault nurse explains evidence left behind from an assault.

“You have someone who’s an expert, who can explain to you that these injuries have occurred and explain what these injuries are indicative of.”

Keats was convicted of one count of sexual assault in the case and sent to prison. He appealed, and the appeal court upheld the conviction.

Nurses can explain evidence

Even if there are no injuries, MacLellan said an expert nurse is still helpful.

“If you have a judge or a justice who is not so used to doing sexual assault cases, it can also sometimes be important to have the sexual assault nurse examiner explain why there’s no injuries.”

Explaining the injuries or lack of injuries after an assault may be difficult for a regular physician or doctor, MacLellan said.

“They may not be as comfortable or not as qualified as an expert.”

But in areas without a formal program, it may be a family doctor heading to the stand.

Dr. Mindrum hasn’t gone to court, and said it’s a role with which neither she nor any of her colleagues are comfortable.

“As an MD you’re listed as an expert witness (but) nothing makes me an expert in this,” the family physician said.

Wilson said physicians and nurses also might not be aware of how to maintain proper custody of the evidence.

In order for the evidence to hold up in court, the health care worker completing the kit needs to ensure they keep an eye on the evidence.

“If that’s not maintained properly, then when you go to court, that evidence may not be beneficial,” said Wilson.

Not the victim anymore

In 2015, during the Miss Newfoundland and Labrador Pageant’s public speaking portion, Courtney Dunne shocked the crowd.

“There were some people whose jaws you had to pick up from the floor,” remembers Dunne.

She recited sexual assault statistics before telling the audience she was part of the stats.

Dunne continued to share her story. From radio airwaves to CBC’s website, the story about the night two men forced themselves on her was spread. Wanting to empower women, Dunne became a voice for consent.

“You’ve got to change it around so you’re not the victim anymore; you’re the survivor,” she said.

Others have since shared their stories of sexual assault with her.

“It opened up the ability for people to be able to talk about it.”

So far, no charges have been laid against the men she alleges attacked her. She was originally discouraged from pursuing the matter by the police, she said. They said it was unlikely the men would be convicted. But she has since asked the police to investigate, and that investigation is ongoing.

Dunne said nothing can’t make the rape go away, but she’s happy she had a rape kit examination and that the nurses caring for her knew what they were doing.

“You want to have confidence in the health care professional that they’re doing it right,” said Dunne.

“If you can’t get it done because someone there is not qualified or they did it wrong, then

that’s just helping the rapist get away with it.”

About the author

Payge Woodard

Payge is a master of journalism student at the University of King's College. She's interned for Bangor Daily News in Maine and freelanced for...