Feminism

Catcalling and the men who do it

Here are the ways women call out catcalling

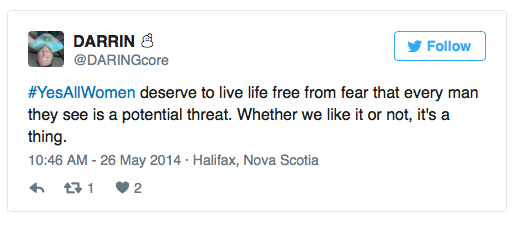

caption

#YesAllWomen deserve to live life free from fear that every man they see is a potential threat. Whether we like it or not, it’s a thing.

— DARRIN ☃ (@DARINGcore) May 26, 2014

“Hey baby.”

“I want to talk to you.”

The comments can seem to come from everywhere, seeping under your skin, causing your hair to stand up on the back of the neck.

The Signal asked women to submit their stories of catcalling, and was inundated with anecdotes — a few of which appear in the block quotes throughout this article.

“I was walking home from school when I was 15, and a bunch of town workers started whistling and calling out at me. They started laughing at me when I walked faster to get away from them.” – Anslea Volks, Waterloo

All of them agreed: catcalling is not a compliment. Yet it persists, happening to women all over the world.

So why does it happen?

How about, “I just KNEW he was the one when he grabbed my arm to stop me from walking away after yelling after me.” https://t.co/BilPudeGUj

— soulsnatcher. (@BeautyOf_TheSun) June 18, 2016

Dr. Tara Perrot, professor and chair of Dalhousie’s Psychology and Neuroscience Department, said in an email to The Signal that catcalling behaviour could be linked to a complex biological phenomenon.

“Theories that would predict males acting in such a way because males, being the sex that is not choosy and can reproduce to full extent by ‘spreading their seed far and wide,’ exhibit behaviours that are in keeping with that,” Perrot said.

“Females, being the choosy sex, because they invest much more by virtue of a more costly sex gamete (the egg) and because of more parental investment, tend to not be so demonstrative in their interest.”

When I was 14 & you beeped your horns at me & shouted obscene things I thought..’Now THAT’S the type of person I wanna be with’ #NoWomanEver

— Katie Anna Siddall (@KASiddall) December 17, 2016

Rebecca Faria is the director of Hollaback! Halifax, the local chapter of an international movement to end street harassment.

She told The Signal in an email that she thinks street harassment and catcalling happens “because the person doing it believes they can.”

“Some believe their impulses are more important than the consent or will of the people they’re harassing,” Faria says. “Some believe they have the right to use sexist, racist, or homophobic harassment to keep other people ‘in their place.'”

“While on a run down by the Commons, a car slowed down and followed me while the man in it yelled ‘nice ass’ at me. I was so humiliated.” – Caroline Korbel, Halifax

Faria believes that often the person harassing others does not realize or care about the ramifications of their actions because “behaviour like that is so normalized for so long.”

Stop Street Harassment, a non-profit organization in the United States, released a report in 2014 that chronicled data from 2,000 people. The resulting data found that 65 percent of women and 25 percent of men in the United States have experienced street harassment.

“I was walking down the street last summer and a group or boys about 14 years old rode by on their skateboards and bikes and cat called me and whistled. It made me feel… sad. Not uncomfortable, because it was kind of laughable that boys that young would have the cheek to do that. But that quickly turned to sadness, because they were so young, and calling at a woman that way shouldn’t be taught at all, let alone that young. It made ended up making me feel very gross and sad.” – Erin Besseau, Halifax

Hollaback! and Cornell University also did an international survey on street harassment. Of the Canadian women they surveyed, 88 per cent had experienced street harassment before the age of 17, and 70 per cent reported harassment before age 15. And 15 per cent of the women reported incidents before they were ten years old.

I was 19 and u were in ur early 50’s & asked if you could take a pic of my breasts for “the boys back home” & I cldnt resist #NoWomanEver

— Lauren Cranmer (@LCTruett) December 24, 2016

These experiences can leave women in fear when they hear a purportedly innocent “hey baby” on the street. In order to avoid harassment, women often “change their routes, behaviour, transportation or dress,” according to the Economist in 2014.

“Walking down the street in Toronto, a black man stopped me and kept saying ‘excuse me, excuse me,’ I thought he needed directions so I stopped and spoke to him. He told me I was hot and wanted to go out with me. I told him that I had a boyfriend and wasn’t interested and he flew off the handle and started yelling, calling me a racist and that I hated black people. In front of hundreds of people on the street. I was so embarrassed and wanted to cry.” – Maggie Horst, Toronto

Some women, however, are using the Internet to fight back. The Twitter hashtags #NoWomanEver, in 2016, and #YesAllWomen, in 2014, called out catcalling.

The Hollaback! Halifax site also encourages women to share their stories of street harassment, with a mapping system that encourages users to point out the places where they stood up to perpetrators of catcalling.

“This doesn’t have to continue,” Faria says. “By giving people a safe way to share their stories, we can reduce the traumatic effects of harassment and keep building momentum for the movement to end it.”

Because when guys make crud comments they end up apologizing to my boyfriend, not me #YesAllWomen

— Erika Cole (@erikahollly) May 26, 2014

“If you don’t feel safe on the street it affects every part of your life, from education to employment to exercise,” Faria says. “Public spaces should belong to everyone.”