Entrepreneurship

Forestry 2.0

caption

WoodsCamp brings logging into the 21st Century

In 2012, the forest industry in Nova Scotia was on the brink of collapse.

Three established pulp and paper mills — NewPage paper mill in Port Hawkesbury, Bowater Mersey in Liverpool and the Minas Basin paperboard mill in Hantsport — were shutting down.

It was a blow felt and echoed, not just throughout the paper and pulp industry, but the entire forest industry. Like a chain of dominoes, sawmills and lumberyards that were dependent on those pulp and paper mills also shut down and small woodlot owners lost their markets and livelihoods.

“The forest products industry in Nova Scotia is not what it used to be,” says Peter Duinker, a forestry professor at Dalhousie University. “It’s still not up to scratch.”

Enter WoodsCamp, a new Mahone Bay business trying to change the way wood is bought and sold.

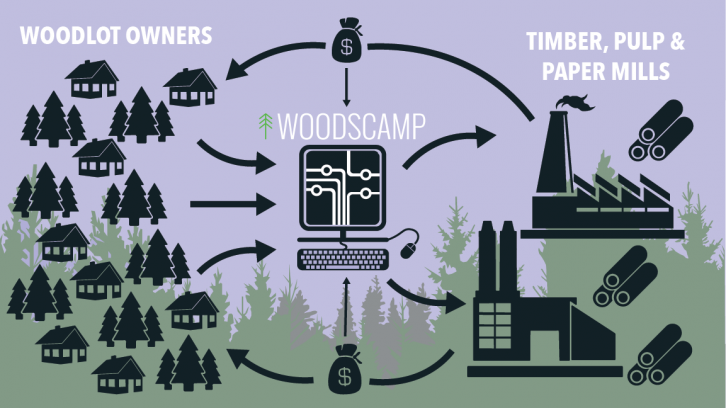

“We’re connecting people who have trees and people who want them,” says WoodsCamp co-founder Alastair Jarvis.

caption

Spruce and white pine trees grow in abundance in Nova Scotia. They’re good for commercial timber, pulp and paper products.A rotting industry

Just how desperate for help is Nova Scotia’s forest industry?

The price of wood is dependent on global commodity markets at a point when demand is at an all-time low; the rise of digital and online media has gutted the newsprint industry, shutting down paper mills across the province; social values and expectations regarding forestry practices have changed drastically over the last 50 years; younger generations increasingly care about the environment. On top of that, most woodlot owners don’t even know the value of their own trees.

It’s fair to say the industry needs drastic change, and soon. These problems are forcing industry stakeholders — logging contractors, saw, pulp and paper mills, as well as landowners — to decide whether or not this an industry worth salvaging.

Entrepreneurs Jarvis and fellow WoodsCamp co-founder Will Martin think it is. They’re trying to get both loggers and private landowners onto one platform, bringing transparency and fairness to the marketplace. If they can achieve that, they believe they can change what they see now as a broken business model.

Since its launch in May, WoodsCamp has had 800 landowners assess their properties through the WoodsCamp website. On average, they’re seeing anywhere from five to 20 landowners signing up every single day.

“I think we need to give the concept the benefit of the doubt and just see where it takes us.” Peter Duinker

To give an analogy, imagine a real estate market where nobody knew the value of their homes, and every once in a while somebody offered you to buy your house for $50,000. How would you know whether that was a fair deal? If you needed $50,000, you might just say yes. That’s bad if you’re selling a house, but it’s also bad if you’re buying one, too. Buyers would just be walking around knocking on doors to see if people were willing to sell their houses.

That’s how the timber industry works. In North America and Europe, Jarvis says, there’s over $23 billion worth of timber that is bought and sold every year from small private woodlots based on a broken model.

The WoodsCamp web platform allows landowners to look up the value of the trees on their properties. It also lets them see the value of other people’s trees. The WoodsCamp software determines the value of the trees. If it determines potential in a woodlot, WoodsCamp will send one of its foresters to do an evaluation of the property.

By signing up, landowners are connected with loggers who may want access to their trees. On the logging side, contractors are given access to a steady supply of a resource they need, when they need it. WoodsCamp takes a cut from transactions made on the platform.

caption

The WoodsCamp model.It’s solving one of the biggest problems in the forest industry – connecting with the landowners. They’ve become increasingly fragmented and harder for loggers to access. Jarvis says many of them either don’t want to sell their trees or don’t know how, and if they do, they don’t trust logging companies to maintain the integrity of their forests. In other words, they don’t want their properties to look like tree graveyards.

Looking for people also costs money. Loggers often don’t know where their next project is going to be. They could be at one end of the province one week, and at the other end of the province the next week, which means more money out of industry pockets and a slow-moving timber market.

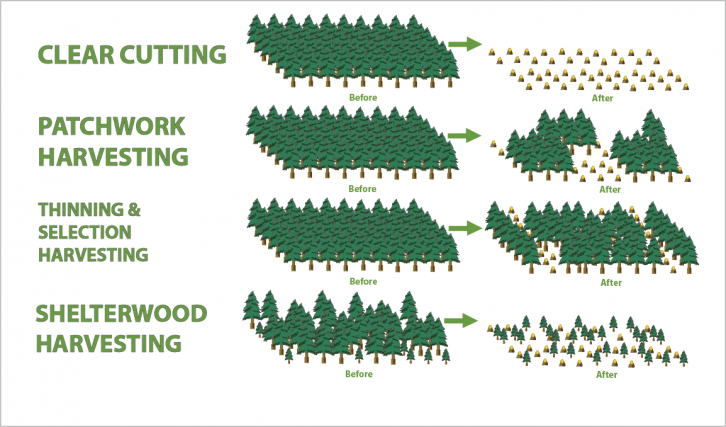

Mills and contractors have to recoup their costs, which means they have to do more intensive foresting like clear cutting. While that can be more profitable, it can also be destructive to natural landscapes.

Duinker, one of Nova Scotia’s foremost forestry academics, likens the WoodsCamp platform to a matchmaker between woodlot owners and contractors. “In between is WoodsCamp where there is some very responsible foresters as intermediaries making sure that the woodlot owners gets two things: one is good value for money, secondly, respectful treatment of the woodlot,” he says.

Duinker says he’s familiar with the founders. He worked with Martin on forest advocacy campaigns for the Ecology Action Centre, which is why he has confidence in the idea.

“I think we need to give the concept the benefit of the doubt and just see where it takes us,” he says.

The founders

caption

Alastair Jarvis is a video game designer turned forestry entrepreneur.The spectacled Jarvis looks like he’d be more comfortable in an office than in a forest. Tall, thin and introverted, he brandishes a thick lumberjack-esque beard and speaks with a jargon-laden smoothness imported from Silicon Valley.

In 2005, he moved back to Nova Scotia to work at a video game company in Lunenburg. He bought a house with a woodlot on it, which posed a minor problem.

“I didn’t know how to manage a woodlot,” he says.

To learn, he became a member of the Nova Scotia Woodlot Owners and Operators Association. It’s where he met Martin.

He left the video game company in 2012, the same year Bowater Mersey Paper Company, a major pulp mill in the area, closed. About 300 workers were shown the door and thousands of landowners were left with one less buyer for their pulp.

“The irony was not lost on me that I was making games for a device that was responsible for the end of newsprint,” Jarvis says. “It struck me as an innovation challenge for the industry – to figure out how to keep these rural communities vibrant in the face of the disruption that was leading to the closure of these mills.”

That’s when Jarvis and Martin started thinking about a potential business. In 2013, they spent eight months talking to potential customers in Nova Scotia and across North America. They identified roughly 30,000 potential landowners in Nova Scotia alone. They started working on it full time during the last year and a half.

caption

Will Martin has spent the last 15 years working as a forester.Martin is the forester on the team. He’s tall, brawny and wears a flannel shirt. He has the beard, but he’s actually a lumberjack. Martin is the one with the technical know-how to run a forestry venture, having already spent 15 years in the industry.

“There was a lot of efforts around ‘how do we encourage more sustainable practices?’” says Martin. “With WoodsCamp, it’s really an incredible opportunity to look at a new business model that supports the kind of practices that I was calling for all these years.”

Making partial harvests profitable

WoodsCamp wants to change the way wood has been bought and sold for centuries. The company’s challenge is to convince people their service has value.

In the WoodsCamp model, rural families profit by maintaining their forests rather than clear cutting them. A rural family or owner of a woodlot can get more income from that woodlot if they manage it for the long-term health of that forest and still have a forest standing at the end.

They do this by adopting a strategy focused on sustainable harvesting.

caption

Clear cutting is the most profitable type of harvesting, but also the most ecologically devastating.WoodsCamp promises to find contractors that will do partial harvests so woodlot owners can still enjoy the natural benefits of owning a forest – enjoying the beauty of the landscape, the wildlife and the ecosystem.

“We’re trying to help people have access to forestry and generate income from their land without having to give all of those things up,” says Martin.

Jim Drescher, woodlot owner and director of Windhorse farms, hires Martin to manage his woodlot. He says the true value of WoodsCamp lies in its neutrality as a middleman and its adherence to sustainable forestry practices. It promises a type of quality control – an assurance that your forest isn’t going to be entirely destroyed.

“You can trust the logger because you trust WoodsCamp.” Jim Drescher

“If you trust WoodsCamp, they will connect you with the harvesters that they trust,” says Drescher. “You can trust the logger because you trust WoodsCamp.”

In the old model, it wasn’t in loggers’ interests to do partial harvests. Those types of cuts weren’t able to cover setup, equipment and labour costs. The setup costs remain the same, but they’d only reap a fraction of the timber. Partial harvesting just wasn’t economically viable on a large scale.

Jarvis says there are other hidden costs in the old model. Loggers have to talk to many landowners to get just one transaction. It makes it more difficult to make the transaction profitable for a smaller job. It also makes it more difficult to do eco-friendly partial cuts – the ones that many woodlot owners want.

WoodsCamp is looking to change that.

“If we can do that in a much more efficient way that covers many more landowners across the province, then we can make it far more efficient for loggers to do partial harvests so that they’re not constantly setting up in opposite sides of the province,” says Jarvis.

Rather than harvesting from a patchwork of woodlots scattered across the province, WoodsCamp allows loggers to concentrate their efforts in smaller areas. It minimizes setup costs, making the economics of partial harvesting more viable.

Kathy Cloutier, a spokesperson for Northern Pulp, a paper mill near Pictou, says WoodsCamp is an “extremely positive” sign of things to come.

“WoodsCamp are using some of the latest forestry technology to help provide these services,” she states in an email.

caption

Alastair Jarvis and Will Martin say landowner associations are trying to solve the same problem in a different way.The challenges ahead

Martin and Jarvis may have a tough time convincing some woodlot owners.

John MacDougall, president of the Federation of Nova Scotia Woodlot Owners, says Nova Scotia should adopt the Finnish model of forestry. He says Finland has over 80 landowner associations that cover the entire country.

“If you want any work done, these forest manager associations have management plans and follow everything through to final harvest,” he says.

There’s a reason why he’s skeptical of WoodsCamp. MacDougall says it isn’t easy to trust a business whose primary incentive is profit. With landowner associations, that’s not the case. He says associations are designed to serve the interests of its members.

Jim Crooker, chairman of the federation and woodlot owner, echoes this opinion.

“I don’t want to see another company trying to make a profit off of what I have as a resource.” Jim Crooker

“I think WoodsCamp is a business that an association can hire to do some of their work, but as a woodlot owner, I don’t want to see another company trying to make a profit off of what I have as a resource,” says Crooker.

Jarvis doesn’t share their concern. “We believe that the tools we’re creating will make co-ops even more effective at what they do and will let them create more values for their members,” he says.

Other challenges include reaching the people WoodsCamp says they would reach. Martin says there were doubts the company could reach aging landowners on the Internet.

“That’s one of the first objections we heard,” he says. “So far, we’re proving that completely wrong. Landowners are most definitely online.”

Surviving the first year

Jarvis and Martin want to expand, but first they have to prove the model works in Nova Scotia.

“That’s what really makes it an investable business,” says Jarvis.

One business expert, Dalhousie University entrepreneurship professor David Roach, has some doubts on the sustainability of WoodsCamp’s business model. “They’re going to have to get to a point where they at least break even on almost all the stuff they need to do,” says Roach.

“This is my concern with web platforms – they look fine from the outside but if you look at what they need to actually maintain the value for the customer, sometimes they highly underestimate the costs.”

Martin says they’re not currently making enough money to cover their costs, but that doesn’t mean they never will.

“We’re a brand new company,” says Martin. “We’re still developing the technology.”

They’re committed and thinking about the next move.

“It could be Maine, it could be New Brunswick, it could be Arkansas, it could be Texas, it could be Sweden,” says Jarvis. “These are all markets who have the same problem.”

caption

WoodsCamp needs to prove the model works in Nova Scotia before it can expand abroad.About the author

Guillaume Lapointe-Gagner

Guillaume Lapointe-Gagner is a freelance journalist based out of Halifax. He currently attends the University of King's College master of journalism...

M

Michel Gagner

J

Jim Crooker