Tackling the doctor shortage

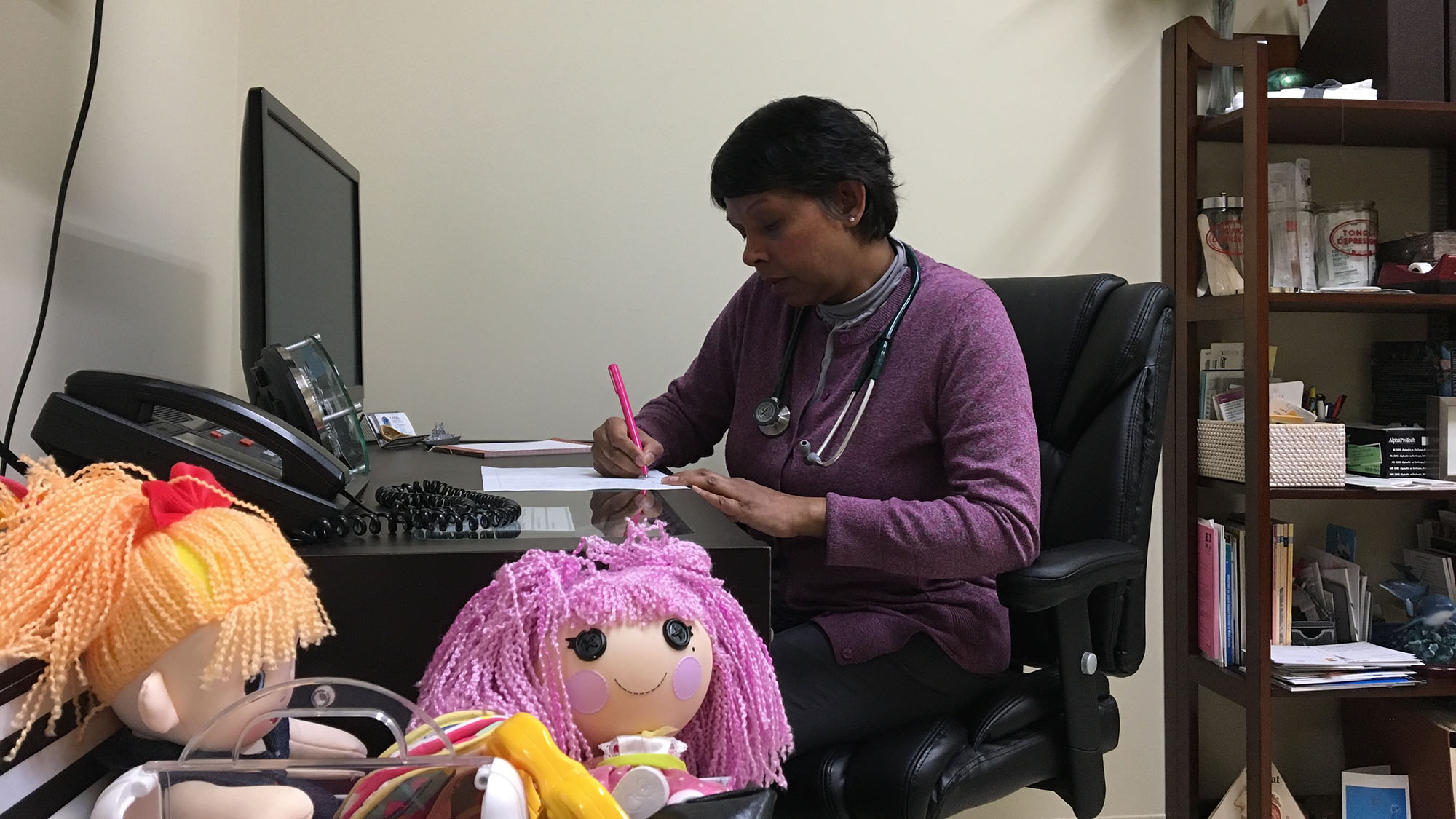

caption

Dr. Ajantha Jayabarathan is a family doctor in Halifax. She has patients as far as Cape Breton because of the doctor shortage.At least 51,000 Nova Scotians are looking for a family doctor. The search is on to close the gap

Sunlight pours into the room from a large window that takes up the entire back wall. There is no need for the lights to be turned on as the sun brightens up the whole room. It doesn’t do much to brighten the spirits of Jennifer MacLean as she stands up and reads on her phone a few hours into her wait in the emergency department at Aberdeen Hospital in New Glasgow.

MacLean isn’t standing because she wants to stretch her legs. It’s because there are 45 people in a 30-seat department on this December day. People are taking turns standing. Others sit on the floor.

She has a rash and wouldn’t be here if she had gotten it five months earlier, when she still had a family doctor to consult. But because that doctor left in June with no replacement, MacLean – like tens of thousands of other Nova Scotians – has to resort to going to the emergency department.

I think there needs to be a change. It’s like we live in a Third World country and that’s how we’re being treated – Jennifer MacLean

After a 12-hour wait she finally sees a doctor, who gives her antibiotics for her rash. Two days later the rash spreads, and she heads back to emergency to get re-checked. This time, instead of going back to the Aberdeen, she makes the two-hour drive to Halifax and goes to the emergency department at the QEII Health Sciences Centre in Halifax. And this time, the doctors correctly diagnose her with Lyme disease.

caption

Recruiting more doctors will mean fewer Nova Scotians have to visit emergency departments for medical assistance.Having Lyme disease without a family doctor forces her to go to a walk-in clinic to consult a doctor, access antibiotics and get the letter she needs for an appointment with Nova Scotia’s Infectious Disease Expert Group. That group specializes in the care of diseases caused by organisms, such as the tick bites that cause Lyme disease. It also means she doesn’t have a doctor here to monitor her condition. She pays for one in Bangor, Maine, even though she pays taxes to get proper health care in Nova Scotia.

“I think there needs to be a change. It’s like we live in a Third World country and that’s how we’re being treated,” said MacLean.

MacLean’s situation isn’t rare. According to statistics from the Nova Scotia Health Authority, there are 51,119 people in the province without a family physician at the beginning of March. That’s the number of people registered on the authority’s Need a Family Practice registry.

People without a doctor are at a disadvantage in terms of the quality of health care they receive. Emergency departments and walk-in clinics across the province are busy with patients, who wouldn’t be there if they had a family doctor. Patients can wait months to see psychiatrists and specialists as well.

Seeking 107 doctors a year

The Department of Health and Wellness and the health authority have stepped up recruiting efforts in the past two years. Nova Scotia’s most pressing needs are for family physicians, rural psychiatrists, emergency doctors, anesthesiologists and internal medicine specialists. There are currently 130 physician job openings in Nova Scotia, and the goal is to recruit 107 doctors a year from 2016 to 2025.

Grayson Fulmer, the authority’s senior director of medical affairs, said the province was on track to recruit 128 physicians this year. That does not mean that there will only be two openings left. Doctors are continually retiring and leaving, so the authority is continuously recruiting. To give an example, CBC News has reported that between 2011 and 2016, Nova Scotia hired 273 doctors but 387 moved out of the province.

We’re leaving no stone unturned when it comes to physician recruitment – Grayson Fulmer

The prime target for recruitment is doctors trained at the Dalhousie Medical School in Halifax. According to Fulmer, half of last year’s 103 recruited doctors came from the school. He added that 89 graduates from the 2017 class had entered the field and 44 of them stayed in the province. Fulmer hopes to improve these numbers.

“I want to get that up a little bit, so we’re making a concerted effort to target Dalhousie students,” he said.

To retain more physicians, the authority is working with Maritime Resident Doctors, which is a volunteer-run organization for Dalhousie medical residents, to try to promote residencies in Nova Scotia. This past summer, the province added 10 family medicine residencies and 15 specialists’ residencies.

“We really are targeting our homegrown physicians,” said Fulmer.

The authority is also recruiting physicians in the United Kingdom, and Nova Scotia has a geographic advantage. If physicians from the U.K. want to return home for holidays, direct flights from Halifax to London are only six hours. The only shorter trip from Canada would be from St. John’s. The second reason is the Nova Scotian college of Physicians and Surgeons, the body responsible for approving licenses, views British and Canadian medical training as similar, making it is easier for a British doctor to receive a license here.

The Nova Scotia Nominee Program helps to speed up a new physician’s immigration. When the authority identifies a physician it wants to recruit, the Nova Scotia government can nominate the physician and their spouse for immigration approval by the Canadian government. Immigration applications can be processed in five to 10 days, instead of the usual 30 days.

caption

Dr. Diarmaid Scully chats with nurse Karina Stanley at the Dalhousie Health Clinic. He is from Ireland and is one of 128 new doctors the province recruited this year.Other incentives for international physicians to work in Nova Scotia include reimbursing a physician and their partner for a one-time visit to Nova Scotia, to check out potential practice sites. The province also offers to reimburse tuition payments up to the maximum amount the doctor would have paid to go to school in Canada. It will also give a $60,000 bursary to a family physician who agrees to work here for three years. These incentives are available to physicians in other parts of Canada as well.

Nova Scotia has had good results so far. The authority started to focus on international recruiting in 2017 and had 10 doctors arrive in the 2017-2018 fiscal year. For the current year, this has more than doubled to 25 doctors. The number may rise for next year. A recruiting team went to London in March and had 30 interviews lined up, plus a waitlist.

Fulmer reports success in recruiting physicians from the United States and South Africa as well.

Towns are pitching in

Individual towns have started to take action into their own hands. In Pictou County, Nicole LeBlanc has been hired to help the authority in the recruitment process for physicians interested in moving to the region. The money for her role comes from the Aberdeen Health Foundation, Pictou County’s municipalities, private business and citizens.

caption

In New Glasgow, Nicole LeBlanc helps recruit doctors in Pictou County.She started last October and her job as the project coordinator for Citizens for a Healthy Pictou County. It consists of three roles. The first is to show off the area to physicians. She also makes it easier for them to move to the region, by helping them with housing, school registration for their children, finding extra curricular activities and connecting them with places of worship. Her third role is to stay in touch with local medical students to try to convince them to move back for residencies and permanent practice.

She has had two physician visits so far but expects this to pick up this summer, when travel is easier.

In the authority’s Northern Zone, which includes Colchester, Cumberland and Pictou counties, 8,938 people were registered, as of March 1, as needing a family doctor.

What is really refreshing about this role is we’re doing something about it, so we’re trying to make some efforts to help make things better for everybody – Nicole LeBlanc

Issues in recruiting and retaining

Challenges remain in recruiting and retaining doctors. In September, Doctors Nova Scotia, Maritime Resident Doctors and the Dalhousie Medical Students’ Society published a report called Road Map to a Stable Physician Workforce. It identified problems that needed to be fixed to have a stable workforce of doctors.

The big issue is payment, both the amount and the compensation format. Doctors in Nova Scotia are the lowest-paid in the country, with an average pay of $262,000 as of the latest statistics the Canadian Institute for Health Information released on Nova Scotia in 2016.

The 2018 numbers are not out yet but Patrick Riley, director of physician services with the Nova Scotia Department of Health and Wellness says Nova Scotia physicians are no longer the lowest-paid in the country.

“Nova Scotia, we have taken significant steps in the last 18 months to increase compensation of our physicians,” said Riley.

There is also an issue about how physicians are being paid, says Dr. Tim Holland, president of Doctors Nova Scotia.

He explains that the number of in-person visits is used to calculate physicians’ pay. This means doctors are treating patients one problem at a time instead of treating all their problems because they need so many visits per day to pay for their practice. Economically, it doesn’t make sense for a physician to consult with a patient over the phone, even if that is the best way to do it.

That is not the only payment format. There are salaried positions called the Alternative Payment Plan used to attract doctors to rural areas with fewer patients.

Right now, you’re paid per one visit per problem, which doesn’t really incentivize being able to look at the whole patient – Dr. Tim Holland

What Dr. Holland would like to see is doctors being paid by how many patients they have, instead of by the number of visits.

“It allows the physician to look at the patient as a whole, instead of a single problem,” said Dr. Holland. “Right now, you’re paid per one visit per problem, which doesn’t really incentivize being able to look at the whole patient. So if you can talk that patient over the phone, via email or for one visit a year, if you get paid the same, that is great.”

The province and doctors are in negotiations for a new contract. Riley said Doctors Nova Scotia has proposed this payment model prior to negotiations.

“I will say we’re supportive of the model, provided that it serves the needs of the public and it fairly promotes what we want which is access of quality of services for patients,” said Riley.

Another issue is reducing administrative burdens for doctors. Dr. Holland said many times when a doctor is filling out paperwork to get medication, the doctor needs to fill out four pages but the pharmacist only needs two lines of it. If they could cut that down it would free up time. And it can take 30 to 40 hours of paperwork for a doctor to switch provinces, which can make doctor recruitment and finding temporary replacements difficult.

Dr. Holland knew a doctor who needed to sign a form and was going to fax his signature, but the process required him to sign it directly. He had to go to the lab at 8 p.m. and leave dinner with his family to sign it.

“That is just absolutely ridiculous, and that kind of thing is rampant in our health care system. It really frustrates physicians to no end and making many leave the province,” said Dr. Holland.

Family physician Dr. Ajantha Jayabarathan has been working in the province for 28 years. She would like to see these improvements, and they should happen soon because doctors talk to incoming doctors about what it is like to work here. She gives them an honest answer.

“The health authority has been very upset that we have somehow been poisoning the well, but what we are doing I believe is responsible because I wouldn’t want to mislead a young doctor that they were walking into paradise because it isn’t that,” she said. “It is unethical as far as I’m concerned, they need to know what they’re up against.”

caption

Dr. Ajantha Jayabarathan works from about 8:30 a.m. to 7:30 p.m. every day so she could take care of as many patients as possible. That is not uncommon by family physicians in the province.What is it like to move here

Dr. Diarmaid Scully moved from Ireland to Halifax last May and started practicing at the Dalhousie Health Clinic in June. He always wanted to move to Canada because he likes that everyone gets free health care and that the country is welcoming to people from different backgrounds. A friend, a doctor in Newfoundland, suggested he try Halifax. Dr. Scully went on tours of practices in Halifax and Toronto and he and his partner liked Halifax. It has friendly people, he says, it’s easier to drive in than Toronto, has nice restaurants, theatre and sports, and it’s a “beautiful city.”

As much as Dr. Scully enjoys living in Halifax, the process of getting here was not easy.

Doctors have to fill out a lot of paperwork for immigration, to ensure the health authority and the Nova Scotia and family physicians of Canada colleges have the correct information to issue a license. According to Dr. Scully, the authority told him it would cost $10,000 for the paperwork when in reality it cost him $24,066. He said he would have to fill out the same forms, such as a police background check, for each organization and pay for it multiple times, when the information could have been shared.

“I would have said half-way through the process, I was considering not continuing with the process, literally because of the bureaucracy involved and because it was so difficult,” said Dr. Scully.

When he arrived, he said he didn’t receive a lot of help. He had to figure out for himself how to get a phone and a driver’s license, when a simple sheet of instructions would have made such tasks easier.

He has met with the colleges and three people inside the authority since October to try to improve the situation. He said they all listen, but he hasn’t seen improvement yet.

“With regards to Irish doctors there is, for instance, social media groups where we discuss things on Facebook and all doctors have gone west (in Canada) rather than east and one of the reasons for that is it is a lot easier to move there than it is to Nova Scotia. Which is a pity because I think they’ll really enjoy it here, it is very similar in ways to Ireland,” said Dr. Scully.

If recruiters can finalize a step-by-step guide on what it takes for doctors to move here, Dr. Scully believes Nova Scotia will be a preferred destination for many overseas doctors.

“The overriding sense I want to get across is that without a doubt I know doctors will be very happy to come here,” said Dr. Scully. “I think there are only positive things to come from Nova Scotia but the powers that be in the government and in bureaucratic colleges have to listen to the doctors on the ground in Nova Scotia. Things need to improve in order to help the Nova Scotian people and improve the health system here.”

I

Ivan Ivanovich Ivanovsky

E

Edie Hippern