Strawberries

Science taking a stab at strawberry viruses

Scientists across Canada are searching for the answers to a Nova Scotian disease

caption

Federal research is hoping to find solutions to Nova Scotia's 2013 strawberry epidemic

caption

Federal research is hoping to find solutions to Nova Scotia’s 2013 strawberry epidemicAndrew Jamieson and Debra Moreau are waiting for the aphids to hatch.

Dark, shiny eggs were collected from the underside of strawberry leaves in the winter and tended in incubators at Kentville’s federal research station.

When they hatch – becoming what one researcher called fat, cuddly bags of sap – Jamieson and Moreau will carefully place them on isolated strawberry plants and watch them grow.

These aphids are part of a federal research project on Nova Scotia’s strawberry viruses. The project started in 2014 after a virus outbreak infected strawberry fields across the province.

The outbreak is under control in Nova Scotia, but the same viruses are present in other provinces across Canada.

“Although the issue started in Nova Scotia … we have the same issue in New Brunswick, P.E.I., Quebec and Ontario,” Moreau said. “I would argue maybe worse than ours.”

Using Nova Scotia as a case study, federal scientists from Newfoundland to British Columbia gathered to look at two questions: what happened in our strawberry fields, and how can we stop it?

What happened?

Greg Webster suspected there was something wrong with his strawberries.

One of the owners of Webster Farms in Cambridge, N.S., Webster used to grow 23 acres of strawberries.

In 2013, the virus exploded on Nova Scotia’s strawberry fields. According to horticulturist John Lewis, the fields had “literally 100 per cent infection.”

Webster found infection on his farm that year. He talked to Curtis Millen, another farmer who had been heavily hit by the virus.

“He basically said you’re going to have a poor enough crop, you might as well take it out before you start,” Webster said.

“That’s what we had to do. We just had to bite the bullet.”

Infected strawberries suffer from what horticulturists call a “decline disease.” Berry size and quality drops, the plant gets weaker and weaker, and occasionally dies. Some types of strawberries also have a yellow edge on their leaves.

That spring, Webster removed 13 acres of strawberries before they were harvested. Many other farmers did the same.

Because many growers opted to remove their infected fields, virus rates in Nova Scotia’s strawberry fields has decreased and the crop has been improving.

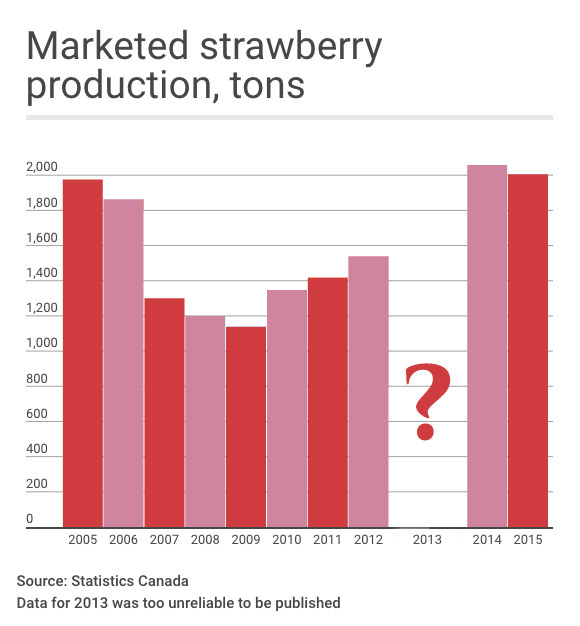

In 2013 there was 50 per cent crop loss, Lewis said. In 2014, that loss went down to 25 per cent, and in 2015, strawberry growers had a bumper crop.

Although no one knows what the crop will look like this year, Lewis said there will be no significant impact from the virus.

How did this happen: virus

In order to figure out how an entire industry was infected in one year, you first need to know a bit about strawberry and virus biology.

When a virus infects a strawberry plant, it injects its genetic code into the strawberry’s cell, forcing it to produce more viruses.

But strawberry cells have a defence mechanism against that process. This mechanism, called RNA silencing, identifies viral codes and degrades them.

Most of the time, this effectively stops a virus from infecting a strawberry plant. But some viruses are better at combating RNA silencing than others.

“Viruses can co-infect plants, and sometimes they help each other out,” said Hélène Sanfaçon, a virologist involved in the federal research project.

“In strawberries there is usually the mixed infections of several different viruses.”

Nova Scotia’s strawberries were infected with two viruses: the strawberry mild yellow edge virus and strawberry mottled virus. Over the years these viruses became more and more prevalent, until there was enough inoculum to start the 2013 epidemic.

How did this happen: aphids

But just having viruses isn’t enough – there also needs to be a way for them to move.

“The wind won’t blow it,” Webster said. “It won’t travel through irrigation water. It’s spread purely by aphids.”

The strawberry aphid, Chaetospihon fragaefolii, is responsible for the spread of many strawberry viruses, including mild yellow edge virus and mottled virus.

It lives primarily on the strawberry plant, overwintering as eggs and hatching in the spring. It creates colonies on the leaves – with many generations of aphids living off the sap of one plant.

In their un-winged form, aphids will only move as far as an adjacent leaf on another plant. But when the colonies become too crowded, aphids quickly transform into winged, fly-like creatures.

caption

This is the winged formed of the Chaetosiphon tomasi, a member of the same genus as the strawberry aphidFrom their home colony, these winged aphids glide on low breezes until they reach another strawberry field or die.

If they come from an infected plant, they bring the virus with them.

“If it’s one plant in a thousand, you just don’t worry about it,” Lewis said. But as soon as a plant gets both viruses, any visiting aphid will transmit both viruses, not just one.

“When you start to get these multiple virus infections in the plant, then they’re essentially spreading disease.”

Before the outbreak, aphids were never considered a big problem in the strawberry industry, said Moreau, an etymologist with the federal research project.

“They were there and growers acknowledged them, but they never really managed for them. They never really got into high enough numbers where it was an issue.”

In 2012, the year before the outbreak, Nova Scotia had one of its hottest summers in 80 years. This likely resulted in an increase in the number of strawberry aphids, which would have spurred more aphids to move out of crowded colonies and onto new plants.

“Perhaps it was a perfect storm,” Lewis said. “You had enough inoculum there, coupled with a real big bad aphid year, and boom. We got high levels of infection in our fields.”

How can we stop it?

When plants are as diseased as the strawberries were in 2013, there’s only one immediate solution: destroy them.

Without the plants, the virus has no place to reproduce. And without the virus, the aphids have nothing to transmit.

After destroying their fields, some farmers like Greg Webster switched to single year harvesting. After a field’s first harvest, it is destroyed and replanted with plants from a virus-free nursery.

Farmers like Webster are also spraying for aphids during the aphid’s flight season, hopefully eliminating the spread of the disease.

Although this tactic has worked well to bring Nova Scotia’s strawberry industry out of the epidemic, it might not be practical for other strawberry markets in Canada.

Nova Scotia doesn’t have many strawberry farmers – and most voluntarily decided to destroy their fields.

“The industry was outstanding, because they don’t have to do anything,” Lewis said. “These are not quarantinable pests.”

If the growers had decided to keep their fields – and not incur the loss of destroying a potential harvest – the virus would have continued to flourish. But not all strawberry growers in Canada have that option.

The research program

That’s why the Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada research program began, so the problem could be understood before another epidemic started.

It joins together three different groups of scientists from across Canada to study the Nova Scotian viruses: etymologists, virologists and horticulturalists.

“Although we’re divided in three, we’re still all working for the exact same goal,” Moreau said.

“We’re looking into this problem in terms of its national scope.”

The project has funding until 2017, and has several experiments underway.

Moreau and other etymologists are looking at the habits of aphids that visit weeds on the edges of strawberry fields, hoping to discover if the virus can hide in those plants.

Plant biologists like Andrew Jamieson are creating a new type of strawberry plant, cross-breeding commercial strawberries and a Chilean variety that shows resistance to aphids.

For Jamieson, research coming out of the federal project is all geared towards long-term solutions.

“If we could put a variety, eventually, that the aphids don’t particularly like, then that would really solve a lot of virus problems,” he said.

Virologists like Hélène Sanfaçon in British Columbia are delving into the genetic codes of viruses. They already discovered a virus in Nova Scotia’s strawberries that had never been documented before.

The three teams are also working together to discover whether the new virus – called SPV1, or Strawberry Polerovirus 1 – is a factor in the strawberry disease.

Lewis had done research on the outbreak before Agriculture Canada got involved, and the federal team has already made advances, but there is still more to go.

“People think the science is all there – we have all the answers,” Lewis said. “The truth is we don’t.”