Standing still

Via Rail's cross-country train spends a lot of time waiting. Via has appealed to the government to help.

Few communities in Canada rely on the train as much as the tiny Namaygoosisagagun First Nation in northwestern Ontario. Tucked on the edge of Collins Lake at the southern fringe of Wabakimi Provincial Park, there is no grocery store and no medical facilities.

The only way in or out, other than portage and snowmobile trails or costly float planes, is the twice-a-week Via Rail train.

On the Via timetable, the community is known as Collins and in recent years, the train’s schedule has been unreliable, sometimes arriving hours after it’s supposed to, causing residents to miss important medical appointments.

“Sometimes it’s a specialist appointment that we can’t reschedule,” said chief Angela Paavola. Related stories

No one knows who built the plywood shack that serves as the community’s designated waiting area. It has no electricity, so those facing long waits at night use candlelight. There’s a small wood stove for heat and members of the community are responsible for firewood. If no one restocks the pile for a long wait for the train, “It’s freezing in there,” Paavola said.

caption

The shack that serves as the railway station for the Namaygoosisagagun First Nation.“We don’t know where the train is most of the time.”

The train that stops at Namaygoosisagagun is Via’s Canadian, the crown corporation’s flagship. While the trip from Toronto to Vancouver is best known as a tourist run, for many people strung along the Canadian’s route across Northern Ontario, the Prairies and B.C., it’s basic transportation. Some depend on it; others prefer it to driving. And with intercity buses vanishing, sometimes it’s the only public transportation available aside from a taxi.

The train became so unreliable that passenger traffic plunged by 23,000, close to a quarter, in 2018, compared to 2017 when the Canada 150 celebrations were underway, and by 11,000 compared to 2016.

Students in the master of data and investigative journalism program at the University of King’s College spent several months looking at the state of transcontinental passenger rail in Canada.

Using publicly available on-time data from Via Rail’s website, the project tracked the performance of Via trains throughout 2018 and to mid-July 2019. The data shows that even after Via added hours to the Canadian’s cross-country journey last summer in an effort to improve record-poor performance, it has struggled to meet its schedule, arriving at least an hour late in Toronto or Vancouver on more than four in every ten trips. If a long-distance train is less than an hour behind, Via doesn’t consider it late.

In between the major centres, the record is worse.

While Via has been increasing service and attracting more passengers in its core markets in southern Ontario and Quebec, last year awarded a $989 million contract for new railcars for that service and has bold plans for a dedicated passenger track in the two central provinces, the King’s class found a transcontinental service that is infrequent and frequently undependable, largely because of freight congestion on the Canadian National Railway tracks it uses for most of its journey.

In its 2018-2022 corporate plan summary, the Crown corporation noted that the deterioration of the on-time performance had “reached the point of being truly detrimental to the viability of the service,” and called on Transport Canada to intervene.

A short trip

The trip from Namaygoosisagagun First Nation to Armstrong, 32 kilometres to the east, takes about half an hour. From Armstrong, a paved highway leads south for the 250-kilometre drive to Thunder Bay, the biggest city in northwestern Ontario, and also home to the closest hospital.

View larger map

Namaygoosisagagun gets money from Indigenous Services Canada to run a van service for the trip to Thunder Bay, to take elders to medical appointments.

Lex Christian Paavola, 25, was one of the drivers last winter. Because there is no heated shelter in Armstrong, when the train was late, Lex Paavola had to wait there with members of the community until it arrived. Getting food late at night was not an option, so he had to pack something to eat.

caption

Residents of Namaygoosisagagun First Nation hoist luggage into the baggage car of the Canadian in Armstrong, Ont.In the fall of 2018, Lex Paavola’s longest wait was 14 hours, he said.

“I chose to work this job because I wanted to be more involved with my community and provide a good service to my elders and family,” Lex Paavola said. But he called the long waits “brutal,” not to mention the economic costs.

Adds Chief Paavola, “Every time (the train is) late like that, we have to pay more and more and that’s out of the money we don’t even have. One-day average in a hotel at Thunder Bay, it costs at least $100…For someone who’s on pensions or who is on welfare, that’s a lot of money and that’s money they don’t have.”

She adds, “For us, it is a belittling experience to have to depend on Via Rail.”

The freight factor

The root of Via’s problems is its heavy reliance on the tracks of freight railways. Via owns only a small fraction of the track on which it runs trains.

Eighty-three per cent of the tracks Via operates on are owned by CN. The remainder of the trackage is owned by Canadian Pacific, and by secondary railways such as the Hudson Bay Railway to Churchill, Man..

While CN’s main lines in southern Ontario and Quebec have two parallel tracks, allowing trains to operate in both directions as cars do on highways, the same is not always so on the rest of its network.

So trains have to share a single track, with short double-track sections called sidings built intermittently along the line to allow opposing trains to pass or overtake one another. The more freight traffic there is, the more Via Trains wait.

“Passenger trains are for the most part shorter than freight trains,” CN said in an emailed statement to the Signal. “This is why there may be more opportunities to put passenger trains in sidings to enhance overall traffic fluidity for all trains.”

Some freight trains are three kilometres long.

Edwin Wilhelm and his wife Donna Teng decided to take the Canadian for a pre-Christmas 2018 trip from their home in Melville, Sask. to Edmonton and back. They were headed to Fort Saskatchewan for three weeks babysitting their three grandchildren and they got a great deal: $200 each for the return journey.

When they arrived at the station in Edmonton for the trip home, they learned the train was hours late. By the time they pulled out after midnight, Train 2 from Vancouver was about seven hours behind schedule.

It just got worse as the train headed southeast.

“We were told when we got past Saskatoon… that they didn’t know when we would arrive because we still had to pass or meet 11 freight trains,” he said. “There were people on the train losing their patience, saying next time they’re taking the bus or going to fly… Would you like waiting all the time 12 hours?”

The final insult came just as they were pulling into Melville. The train halted for well over an hour, just short of the station.

“I could see the Co-op gas station,” he said. “I could have just got out and walked through the field and been home in two, three minutes.”

The couple arrived home nine hours late.

Such delays are common on the Prairies, analysis of the on-time performance data shows, with the Canadian standing still hundreds of times, at various points, for periods ranging from a few minutes to more than two hours, over the last year. Standing for 40 minutes of more is not uncommon.

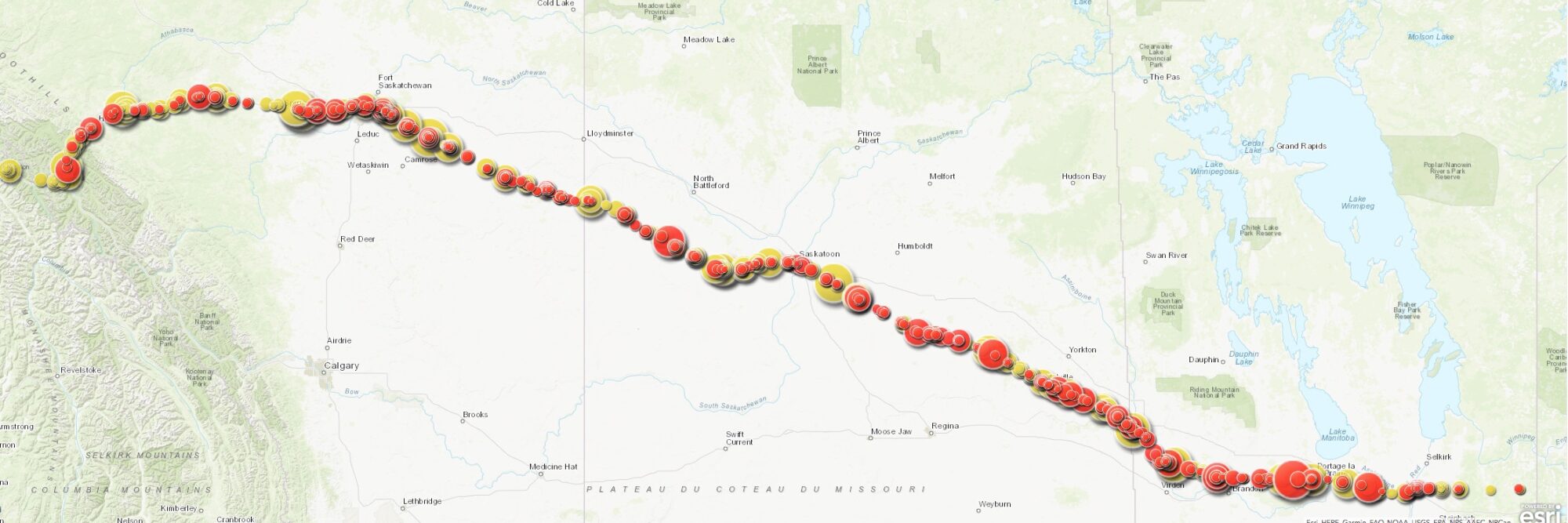

Mapping a late train

This map shows the progress of Edwin Wilhelm and Donna Teng’s train on its full journey from Vancouver to Toronto. Each dot represents a location for the train from Via’s on-time-performance site, while the dot’s colour indicates how late the train was at each point along the way. Clicking on each point gives information such as the local time, the next station coming up and the number of hours late the train was at that time.

View larger map

Via has not been shy to attribute delays to freight trains, and its proposal to build its own dedicated line between Toronto and Quebec City is largely predicated on the idea that its trains will be far more reliable if they are running on trackage Via owns. Indeed, Via reports that on its own lines, its trains are about 94 per cent on time.

We spoke to one CN employee who works on the Prairies and who asked not to be named because he is not authorized to discuss internal operations.

The employee said that despite what people might think, giving passenger trains priority is a “cardinal rule” of railroading.

But the realities of railway operations make that ideal difficult to attain.

“The corridor between Edmonton and Winnipeg, there’s a lot of (freight) trains, you know, there’s terminals across the system that see over 100 trains … in and out every day,” he said.

“The majority of Via Rail’s delays probably are attributed to CN,” the employee said. “But it’s not because we’re taking priority and we want to move our trains first, it’s just unfortunately when there are delays, whether it be engineering, mechanical or transportation-related delays (on freight trains), Via Rail will take a hit just like CN trains take a hit.”

caption

In this undated photo, a tank car is seen through the window of Via Rail’s Canadian train in Edmonton.Indeed, the company is in some ways the victim of its own success, with a huge surge in traffic and revenues straining the ability of the company to get goods from A to B efficiently.

Millions in new capital spending

CN has lately been spending millions building new sections of double track on the Prairies. According to the company, it planned to add about 100 kilometres of new double track in Saskatchewan and Alberta as part of a $3.4 billion capital program in 2018 and will build almost as much this year. In its emailed statement, CN said the $7.4 billion spent over the two years, “will support the safe and efficient movement of all our customers’ goods and, in this case, Via’s passengers.”

As of May this year, about 750 kilometres of the roughly 4,000 kilometres of CN lines used by the Canadian going west were double tracked, the railway said. Another 270 kilometres through the narrow Fraser Canyon in B.C. are effectively double tracked as both railways use CP’s track eastbound and CN’s westbound.

Even so, three quarters of the Canadian’s route remains single tracked.

Via recently signed a new three-year contract with CN for the operation of Via trains on CN’s tracks. The details are kept secret by both parties.

“(There’s a) huge cone of silence on all of that, which is amazing,” said Doug Smith, who was a rail policy analyst for Transport Canada who oversaw Via Rail’s budget from 1982 until 2012.

“Partly as a result of what would I call the freight railways not wanting to have their numbers scrutinized and Via Rail treating it as a huge marketing issue.”

One thing is clear: revenues from Via are an insignificant drop in the ocean of revenues CN earns from hauling freight.

Writing in the London Free Press in 2015, then CN CEO Claude Mongeau said that each run of the Canadian earned CN less than $25,000. With more than 250 total runs of the Canadian in 2018, and assuming the rate was about the same, Via would have paid CN under $7 million in 2018 to operate the train. CN did not respond to a query as to whether the number is valid today.

Compare that to CN’s freight revenues in 2018 of $13.5 billion, including $2.4 billion from moving grain and fertilizers, and it’s not hard to imagine where the company has to put its priorities. Total passenger revenues are not broken out by CN in its reporting and Via is never mentioned.

Powerless

Many of Via Rail’s troubles can be traced back to the way it came to be.

The Liberal government of Pierre Trudeau created Via in 1977, first as a subsidiary of CN, which was crown-owned at the time, then as a separate crown corporation. Via took over the heavily subsidized passenger services previously operated by CN and CP.

Its only shareholder is the federal government, and Via could be eliminated just as quickly as it was created. Indeed, vast swathes of Via’s original network were shut down over the years by Liberal and Conservative governments seeking to reduce hundreds of millions of dollars in losses.

Via Rail required a $273 million operating subsidy from the federal government in 2018. Each passenger on the Canadian is subsidized to the tune of almost $600 on average, while each passenger on the Ocean between Montreal and Halifax is subsidized close to $550.

There is no Via Rail legislation to lay out a mandate or impose accountability on Via or the freight railways that host its trains, so Via’s fate rests with the minister of transport of the day, and the federal cabinet.

“Not only is the federal government the owner of Via Rail, but it’s also the regulator of railways. So it has all the capacities to make Via Rail better but chooses not to do it,” said Malcolm Bird, a political science professor at the University of Winnipeg whose research focused on Via Rail and other Crown corporations.

Bird said when he mentions the federal government “chooses not to” do anything about Via Rail’s delays, that implies that it has actually captured the federal government’s attention — Bird doesn’t think so.

“The problem is, does the needs of northern rural small-town people — many of whom are Indigenous — is that really a political concern for the federal government? And I would say it isn’t,” Bird said.

“If our communities are relying on seniors to remain in our communities and pay taxes for their homes and the services that are offered in this region, we have a huge problem here if we are going to retain them, if these people can’t get to and from safely and reliably and comfortably,” said Éric Boutilier, founder of the advocacy group All Aboard Northern Ontario.

“In terms of reliability, it is hard for people to use a service when, particularly in the winter time, it gets to -30 or -40 degrees, depending on where you are. Some of these places don’t have heated shelters, so the person is waiting either in the vehicle, if they have one, or they are waiting outside.”

The federal government needs to provide the tools for Via Rail to be able to operate properly, he said. “Unfortunately, at this point, the federal government really hasn’t taken a whole lot of concern with respect to this issue to date.”

Grain Power

One group that does have clout is farmers, and especially western Canadian grain farmers.

How the railways move grain and what they charge for it has been an issue since the first Canadian transcontinental railway, the CPR, pushed west in the 1880s.

In 2014, congestion on western rail lines resulted in delays in grain shipments that were so bad the federal government stepped in and started fining CN and CP, Smith said.

In 2014 the Canadian government created the Fair Rail for Grain Farmers Act, which amended the Canada Transportation Act. The new act ordered CN and CP to move grain shipments in a certain amount of time or they would face fines of $100,000 per day.

“Prairie farmers exert a huge influence well beyond their numbers when it comes to movement of freight, and governments listen to them,” Smith said.

“The farmers are one of the few groups that are actually able to exert enough pressure on the federal government to get the railways to do what they want to be done, which in this case is move the grain,” Bird said. “The federal government has the tools to be able to change CN’s behaviour.”

And the grain issue is a perfect example, Bird said.

Last spring, after a leadership shuffle that saw CEO Luc Jobin depart suddenly, his interim replacement, Jean-Jacques Ruest, said the company would move “immediately” to improve the movement of grain. CN said it was “directing additional people and equipment to clear backlogs across its network.”

There were no similar releases from CN about Via.

“When it really matters, when there’s a group that’s able to exert real political pressure on the federal government, it’ll act. But such does not hold for poor old Via Rail,” Bird said.

caption

A visualization of delays of Via’s Canadian across the Prairies in the latter half of 2018 and to the beginning of June 2019. Red circles represent places the westbound Canadian sat standing at locations more than 2 km from Via Rail station stops, yellow circles the eastbound Canadian. The size of circles shows the relative length of delays, which ranged from roughly 20 minutes to more than two hours. Not all delays or time periods are shown. Source: King’s MJ class analysis of Via on-time dataThose who rely on Via Rail for transportation are a much less powerful constituency than farmers in Western Canada.

“CN basically sets whatever Via Rail is going to get,” Smith said. “If you send a letter to the government, I think you’ll get something back along the lines that Via Rail is a Crown corporation, the government doesn’t get involved in its day-to-day operations.’”

For Greg Gormick, a transportation policy advisor with On Track Strategies, that’s unacceptable.

“It’s not just two private companies. Somebody needs to be there protecting the public carrier that runs with public money.”

Smith said Via did have some protections in legislation, before CN was privatized in 1995. At that point, all mention of passenger rail was removed from the act so it wouldn’t hinder CN being sold, Smith said.

“Sometime later I was successful in persuading people that we should put in section 152 (of the Canada Transportation Act,” Smith said. “It gives Via Rail the right to go to the Canadian Transportation Agency with complaints about service from the railway.”

But Via has only taken advantage of that once. Gormick said he understands why.

“(Via Rail complained about) CP when they didn’t want to honour an agreement about the number of trains going through a junction in Smiths Falls (Ontario). They took them to the CTA and Via Rail won,” Gormick said. “But they won’t do it with CN because 83 per cent of all their train miles are run on CN.”

Gormick said that Via Rail is concerned that if Via Rail complains to the CTA over one route, CN will retaliate.

In the past five years, five private members bills have been introduced in the House of Commons in an attempt to advance Via’s cause and that of its riders. As with most such privately sponsored bills, none has passed, and the government has not proposed anything new. London-Fanshawe’s NDP MP Irene Mathyssen introduced her proposed Via Rail Canada Act in October 2017.

“What we’ve seen over the last 20 years is a decline in service and an entity that simply abandons communities, and it started quite early on with Via Rail dropping service to remote communities or parts of the country, and that’s escalated,” Mathyssen said.

“I wanted there to be a sort of an oversight, legislation that just says, ‘Alright Via Rail, you have been given an opportunity to use the right of way and the infrastructure, but you have to absolutely fulfill your commitment to communities.’ ”

The bill would require Via to publish statistics on its website about its on-time performance, and if it fell behind on more than one in five trips in a six month period, Via would have to report to the minister of transport “identifying the causes of those delays and the measures to be taken to improve compliance with the railway timetable on that route.”

The decline of Via Rail’s western transcontinental route has been cited in every annual report published online since 2004. And every annual report mentions the cause of delays: freight congestion.

An urgent fix

A year ago, Via faced catastrophic delays averaging close to a day in some months, and more than 40 hours in one instance in May. Not surprisingly, some customers were pretty unhappy.

@VIA_Rail Check out my unforgettable view of the Rockies on my family’s very expensive trip on the Canadian from Jasper to Vancouver – left 12 hours late at 2am. @DestinationCAN @ExploreCanada pic.twitter.com/ELFhr651U5

— Michael Clarke (@mikegclarke1) July 18, 2018

The railway was feeling it in the pocketbook. In 2018, the number of passengers who rode the Canadian was down almost 23 per cent from 2017, from 104,900 to 82,100. Revenues were down $2.7 million.

The company knew it had to do something. The answer wasn’t to make the existing schedule work better, but to add more time.

The Canadian’s schedule had already been lengthened in 2008 with the addition of an extra night. Via and CN added yet more time to the run, starting on July 26, 2018, with the total running time on the new schedule getting close to 100 hours.

The westbound train got more than eight extra hours to make its trip, and the eastbound 13.

As of last summer, the Canadian was scheduled to take roughly a day longer than CN’s fastest passenger runs of more than 60 years earlier, in 1957. At that time, CN’s Super Continental clocked in at 70 hours westbound and 68 and a half eastbound.

The extra time added a year ago was not spread evenly along the route. Analysis of the Via on-time-performance data shows many delays for Via Trains in the central and western Prairies, and in both directions the new schedule added hours in those areas, with a further sharp increase in B.C. on the westbound run and toward Toronto eastbound.

caption

Comparatively speedy: the CPR’s Pacific Express, seen here in the Kicking Horse Pass, sometime in the 1890s, had a faster schedule from Mission B.C. to Vancouver in 1892 than today’s Canadian does from Abbotsford to Vancouver, a similar distance.The last stretch of the westbound route, roughly 75 km from Abbotsford to Vancouver, is an extreme example of how the schedule was padded. It’s a congested corridor, and the Canadian’s schedule now allows four hours. To give a sense of how stretched out that part of the schedule is, even the CPR’s Pacific Express in 1892 could do about the same distance in less than half the time allowed for the Canadian in 2019.

Improvements

The new, lengthened schedules had an immediate impact. Before the change, from January to July, 2018, the Canadian was late on virtually every run and the delays compounded to the point where some trains ended up leaving the day after they were supposed to.

After the change, the Canadian began arriving early on many of its runs, at least for a while. Analysis of the Via data shows the train soon started falling behind even the new extended timetable. The Canadian has failed to arrive within Via’s 60-minute grace period on more than four in ten runs overall since the changes, despite all the extra time built in.

“Adherence to published schedules has been markedly better with the lengthened schedules,” Via said in its emailed statement, “but still leaving much room for improvement.”

But while those travelling right to the end of the route are more likely to arrive on time, that’s not always the case at intermediate stations. At Armstrong, Ontario, where people from Namaygoosisagagun First Nation must travel to reach Thunder Bay, the westbound Canadian has been an hour or more late slightly less than 50 per cent of the time in 2019, while the eastbound run has been at least that late more than 80 per cent of the time.

In its emailed statement, Via said, “While the primary focus of recent schedule changes (2018 and 2019) is indeed on improving departure and arrival times at origin, destination and major en route stops, Via Rail is very conscious of the need to ensure that improvements also benefit smaller stops, whenever possible.”

It notes it takes “significant efforts” to ensure passengers boarding at intermediate stations are kept informed of any significant changes to the trains schedule, as they occur.” At the same time, Via acknowledges that in more remote areas along the Canadian’s route, its online system that reports trains’ on time performance, is unreliable due to spotty cellular coverage.

Mapping a generous schedule

This map shows an example of the Canadian leaving Toronto on July 7 of this year. The train can be seen to be later and later as it continues its westward route, but ends up only a couple of hours late on arriving in Vancouver. Click on individual points to see how late the train was at any given place.

View larger map

A “national embarrassment”

One thing the schedule change of last summer did was nearly eliminate the problem of the Canadian leaving its origin stations already hours behind, because the incoming train was so far behind schedule. In May 2017, the compounding delays had become so bad that two departures of the Canadian were cancelled in a bid to get the schedule back on track. Now, the train usually departs close to on schedule even if it often falls far behind schedule on its run.

Ryan Brook calls the state of the Canadian a “national embarrassment” and says it should either be fixed or shut down.

Now an associate professor at the University of Saskatchewan, he grew up around trains.

His father worked for CN so they used to ride on Via for free until his dad retired in the ‘90s. Since then he has used the remote train to Churchill, Manitoba for a periodic class trip for his students, but in the last year or so he has given up travelling on the Canadian, which runs through Saskatoon where the university is located.

“Certainly I remember as a kid having these amazing conductors with the fancy suits, and they would give us cardboard cutouts of the trains we could put together, and…you’d sit together as a family in the dining car and have these great meals. And just a wonderful travelling experience.”

He calls the delays of today, waiting for freight trains to pass, “catastrophic.”

“Certainly, sometimes I’ve spent more time sitting in these spurs waiting for trains to whiz past us than we actually on the rail travelling to our destination.”

Via is painfully aware of the problem, as it notes in its corporate plan.

This situation is a serious embarrassment for Canada’s reputation and the Canada brand, in North America and abroad. Travellers return home with the lasting impression wondering how a G7 nation cannot operate its trains on time.

The on-time performance on Via’s other major long-distance train, the Ocean between Montreal and Halifax, is better but it still has its share of late runs. Between March 2018 and March 2019, the Ocean was late about 20 per cent of the time overall, according to the King’s analysis. Performance was worst in the winter months, and Via blames that on the weather. CN attributes the generally better performance of the Ocean to its much shorter route. When on time, the Ocean takes about 22 hours, with track conditions requiring slower speeds in parts of New Brunswick. Via says it is considering the purchase of 275 kilometres of CN track in the province.

caption

Passengers board the Ocean in Moncton, N.B. on Nov. 19, 2018Via recently changed the Canadian’s schedule again, as of the last day of April. The change lengthened the westbound run from 95 to about 97 hours, and shortened the eastbound time from 95 to about 92.5 hours. The departure from Toronto was also moved from the late evening to mid-morning. After the latest change, the westbound run arrived in Vancouver early about eight in ten times in May and June, and late the remainder of the time. The eastbound train arriving in Toronto was late six runs out of ten in the same time period. The first half of July saw almost all trains, in both directions, arrive at the final destinations late.

Via also agreed with CN to cut back on the summer schedule of the Canadian.

Since 2012, Via has run the train twice a week in the fall, winter and early spring and three times a week in the summer tourist season. For now, the two-day schedule will apply year round, except for in summer in the mountains, when the third train operates between Edmonton and Vancouver only. That train arrived early on almost all runs to Vancouver, and late on every run to Edmonton, in May and June.

Via notes that the new schedule lengthens what it terms “dwell times” at some intermediate stations, again allowing trains to catch up when they get behind schedule.

Being realistic

It’s not just in Canada that CN is criticized for delays in passenger trains operating on its tracks. In its latest report card on its host railways, for 2018, the U.S. passenger train operator Amtrak gave CN a D-, up from an F the year before. Canadian Pacific, which also owns track in the U.S., got an A in both years, top among all railways.

CN maintains it does its best to keep Via trains on time while keeping all trains flowing smoothly.

“Schedules are worked out collaboratively between CN and VIA,” CN said in an emailed statement. It added, “Schedules need to meet passengers’ requirements while being operationally realistic.”

But Via says despite a cooperative relationship with CN to realign schedules of the Canadian in 2018, negotiations with the freight railway won’t resolve all the issues.

“A mechanism to ensure reasonable and predictable [on time performance] for the Canadian (as well as for all passenger trains) requires implementation, as currently there are no repercussions for the host railway for such poor performance,” the 2018-2022 corporate plan said.

“Transport Canada must consider intervening and provide assistance in delivering an equitable arrangement.” Asked if an approach had been made to the government on the issue, Via responded, “This is where things stand at the moment.”

The beginning of 2019 produced some modest good news in ridership, with revenues and passengers rebounding during the more lightly travelled winter months.

But for those who rely on the train for more than a beautiful ride through the mountains, eliminating the third summer run east of Edmonton is going to make their transportation woes even worse.

“It’s awful because our life is almost scheduled around that train,” said chief Paavola of Namaygoosisagagun First Nation.

“How do we get out? So now we’re going to have to continue the winter schedule —two trains west and two trains east and there’s a big gap in between.”

Paavola has tried reaching out to Via Rail. She is still uncertain of who she should talk to about the impact on her community.

“We have questioned. We have not raised (an issue). I wouldn’t even know who to go (to). I’ve asked, ‘Who do I speak to?’ ” Paavola said. “You Google it and it’s somebody sitting out in Montreal or Vancouver, so who do you actually talk to? Like, who is the actual boss? Who is looking after Via Rail?”

The main dataset for this story was collected for Via runs from June 16, 2018 to July 14, 2019.

The students who worked on this package were Lyndsay Armstrong, Laurianne Croteau, Bethanee Diamond, Nicholas Frew, Will Gordon, Sonia Koshy, Yuqian Li, Megan O’Toole, Colin Slark, Jessica Sundblad and Olivia Blackmore. Their instructor and supervisor was Fred Vallance-Jones. Web support and video production by Jeffrey Harper. Special thanks to Mingsze Ho of Esri Canada for technical advice.