Anti-vax

The vax of the matter

caption

Andrew Mader believes vaccines are harmful and caused his son Ethan's autism.Anti-vax has been deemed a global health threat. Disease outbreaks are on the rise. Science and belief clash over vaccinations in Nova Scotia

Within a week of his son’s 18-month measles, mumps and rubella vaccination in 2011, Andrew Mader was concerned. Ethan was having diarrhea and vomiting more than usual, and he was no longer making eye contact. “His eyes were rolling around in his head,” Mader says. He wondered if Ethan had gotten into something under the sink, or been poisoned some other way. “He was learning to eat, he was learning to talk, everything was going the way that it should’ve. And then all of a sudden, he made a complete 180.”

Mader and his wife brought Ethan to the doctor. “She took one look at him, she was like, ‘yeah, we’re sending him to autism research,’” says Mader. They soon found themselves in a new world, answering “several hundred” questionnaires, and seeing specialists for psychological tests. There were IWK Health Centre appointments and home visits. “It was all psychological testing,” says Shannon, Mader’s wife. “Nobody tested his bowel problems.” Ethan was diagnosed with severe autism.

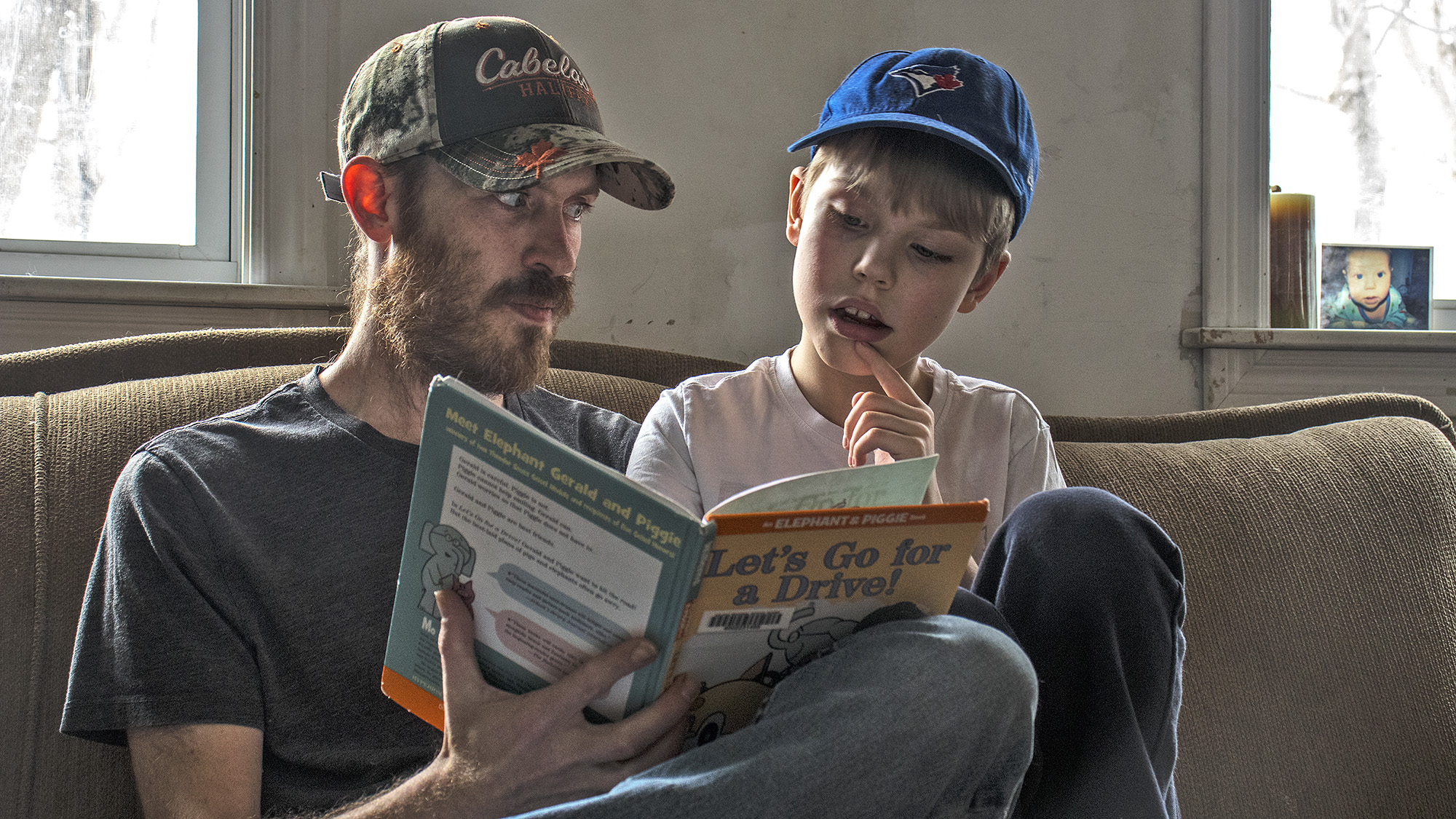

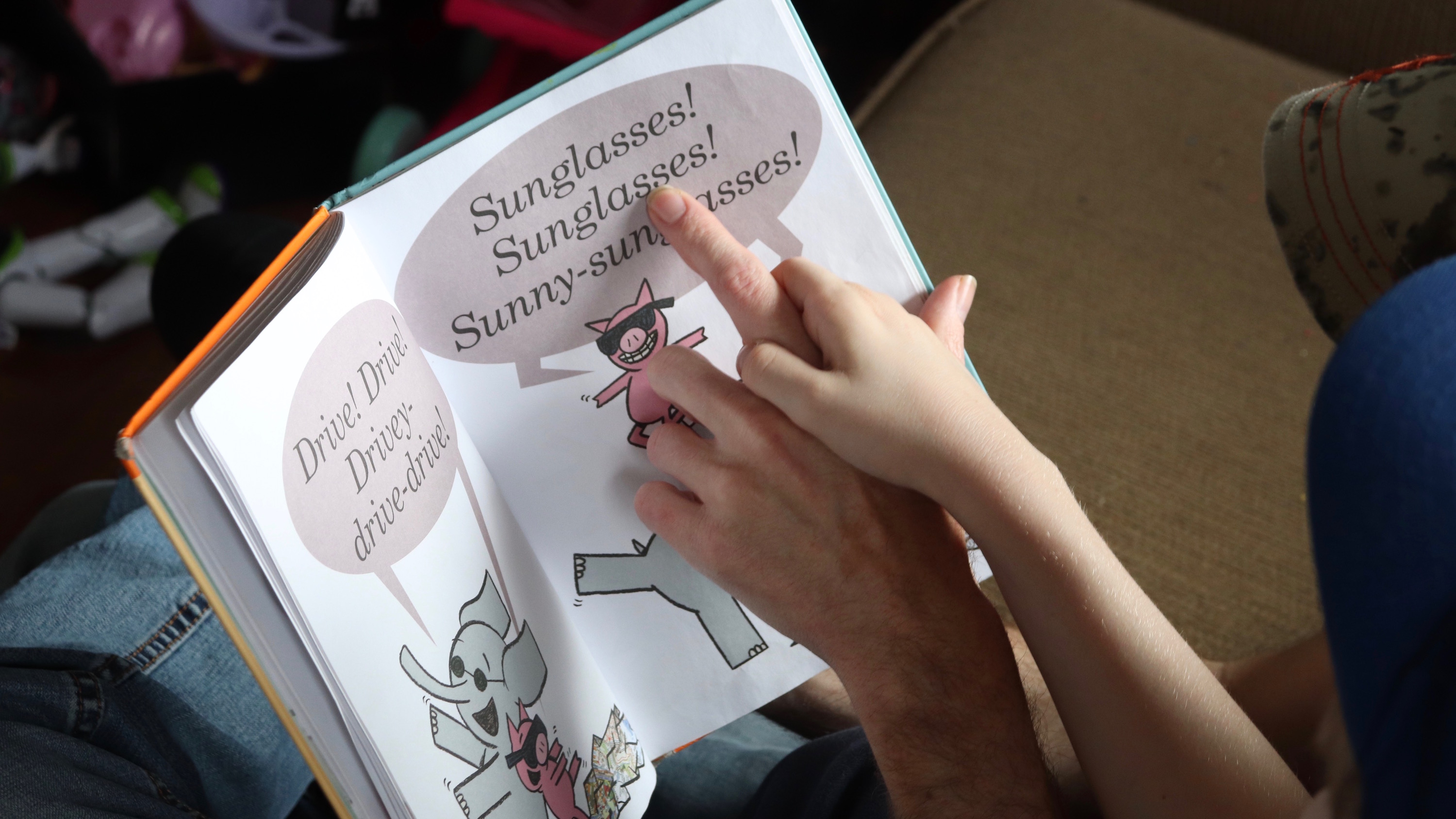

caption

Andrew Mader reads a book with his son Ethan. Mader questions every aspect of vaccines, from ingredients to doctors’ education.The next several years involved more trips to the IWK and interactions with specialists to help Ethan become as functional as possible. Autism is a developmental disorder that impacts brain development and can result in impaired communication, social difficulties and repetitive behaviours. It is sometimes accompanied by epilepsy, autoimmune conditions or gastrointestinal problems.

Mader didn’t think the psychological approach was right. He says he is sure Ethan’s problem is toxins. “That’s what got me involved in actually getting into vaccines, is that I knew that there was something physically behind it that no one was addressing,” he says. Ethan’s stomach problems were chronic. The doctors’ advice to give him Immodium, an anti-diarrhea medication, didn’t satisfy the Maders. They wanted him cured. They discovered their well water was tainted with arsenic, but they were sure he had been poisoned mostly by vaccines.

I just kept on getting further and further into it and I just … it’s now almost like a religion.Andrew Mader

Eventually, Mader came upon a wealth of information: anti-vax pages on the internet. He says it took a week for him to become convinced that vaccines cause autism. “I just kept on getting further and further into it and I just … it’s now almost like a religion,” he says.

The material answered all his questions. Ethan’s stomach, he learned, was upset because of toxins contained in vaccines. Children these days receive vaccines for more diseases than ever before, he read, so the toxins add up and make kids sick. Mader, who now distributes wellness products for a company that promises “safely ridding the body of harmful toxins,” came to believe ingredients like aluminum caused Ethan’s upset stomach, and his autism. Today, Mader moderates a Facebook group called Nova Scotia Alternative Autism Awareness and Biomedical Support that boasts 296 members.

He still believes vaccines are poison. “I don’t accept them as a form of preventative medicine, or as safe, or as effective. I think it’s a ginormous scam.”

A history of anti-vax

Negative views of vaccines are as old as vaccines themselves. Alfred R. Wallace, co-founder of the theory of natural selection alongside Charles Darwin, claimed in his 1889 book Vaccination Proved Useless & Dangerous from Forty-Five Years of Registration Statistics that “vaccination has not diminished smallpox.” He was a high-profile anti-vaxxer before such a term existed.

caption

Alfred R. Wallace wrote an early book criticizing the smallpox vaccine.These days, you can find a PDF of Wallace’s book among a dizzying spread of material that constitutes the anti-vax canon. There are movies, periodicals, books, blogs, news sites, YouTube channels and Facebook groups. The pages number in the hundreds, if not thousands. Seven of Amazon’s top 10 best-selling vaccine books say vaccines are harmful. Search for “vaccine injury” on Google and one of the top results is an anti-vax website: Vaccine Choice Canada.

Adding to the pile are debunked and retracted articles that remain on databases. For example, an article published in the British Medical Journal, “Public Should Be Told That Vaccines May Have Long Term Adverse Effects” by John Classen concludes that vaccinations could cause diabetes. Several other research studies also published in the BMJ have found no link whatsoever. The claim is considered “unfounded” by other researchers. However, the article remains on the National Library of Medicine’s NCBI database. The only sign of the other material is a narrow yellow bar on the page saying, “this article has been cited by other articles.” It is still shared among anti-vaxxers as evidence that vaccines are bad.

It’s basically easier to write these things than to work out why they’re wrong Carl Miller, social media expert

The proliferation of easily-found anti-vax documents, and easy-to-understand interpretations of them, lends credibility. Readers have complicated research explained in simple and certain terms. The dominant narrative is questioned and criticized. Any doubts raised are treated as proof the dominant narrative is wrong.

This accessibility leads to a sense of real understanding. Mader says he was convinced by anti-vax material because “there was actual fact behind the stuff that was more vaccine hesitant, where it was nothing but fluff and doom porn on the pro-vax side of it.” This is a common belief among anti-vaxxers. “All we find is validation,” he says.

According to British social media expert Carl Miller, anti-vax material is potent because “it’s so much easier to poke holes in a narrative than it is to build your own. And I often feel that that’s the way this debate goes. They try to demonstrate their point of view is the correct one by trying to demonstrate that the mainstream view is flawed. It’s not the same thing.”

While some questions may be reasonable, the conclusions of anti-vax material are not. “There’s always something which empirically cannot be true. An implication is stretched way too far, or an underlying model just doesn’t work. There’s always something there, but it’s exhausting and time consuming to debunk it because it’s basically easier to write these things than to work out why they’re wrong,” says Miller, research director at the Centre for the Analysis of Social Media in London.

He sees the anti-vax movement as one of many conspiracy theories amplified by community building on social media. And these communities are growing. “They’ve found fellow travellers spread across the world, they’ve formed a lot of links between national and local groups, across geographic boundaries,” he says in an interview via Skype. “They’re really good at spreading their message … and packaging of ideas to make them spread well in forums, even before social media. Since 2010, I’ve seen the movement get bigger and bigger.”

caption

“These online subcultures and movements are just spilling into the mainstream in a really astonishing way,” says Carl Miller.Miller has studied online conspiracy theories for some time. He says inequality is a driving force. “The people that tend to believe it, and the people that tend to spread it and be part of the movement, are people that are most distant from conventional centres of political and economic power. So, it’s a lot easier to think that 9/11 was caused by the CIA if you’ve never met anyone in the CIA or you’ve never had anything to do with government, because it seems more closed.”

The grand conclusions that can result are what make anti-vax a conspiracy theory. “An essential part of a conspiracy theory, rather than just a wrong fact, is the idea that there is this cabal of cooperating elites that is, through malfeasance and hidden methods, seeking to control the wider populace,” says Miller. The idea that Big Pharma, doctors and governments are peddling poison disguised as medicine is another common belief among anti-vaxxers.

Clarifying the truth

Compounding the confusion is a grain of truth present in some anti-vax claims: vaccines contain aluminum, toxic in high doses; the people in charge of research and distribution of vaccines, it is argued, have conflicts of interest; vaccines, it is asserted, cause autism; fetal tissue is used to make some vaccines – or, in Mader’s words, “there’s a lot of dead babies inside vaccines.”

According to the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, there are no dead babies in vaccines. There are human cells used to make some vaccines. The virus is grown in connective tissue cells called fibroblasts descended from two voluntary abortions conducted in the 1960s. Scientists have kept those original cells multiplying. No other fetuses have ever been used to make those vaccines.

“Some human and animal cell cultures are used in the early stages of production, but these are all removed – and it’s only in some live vaccines, not all vaccines – these are all removed during the purification process,” says Elaine Holmes, a director at Communicable Disease Prevention and Control, a branch of the office of the Chief Medical Officer of Health for Nova Scotia. “So, when you get a vaccine injected into your arm, there is no human and/or animal cell culture in it.”

Dr. Joanne Langley, chair in pediatric vaccinology at Dalhousie University, says aluminum salts are in vaccines, and make vaccines more effective. However, it does not amount to a toxic dose, even when you add up all the shots a person gets in their lifetime. A baby will get more aluminum from breastmilk or formula than from vaccines. It does not stay in the body, nor does it go into the brain. “It’s processed by the body, and we get rid of it,” she says.

caption

“No one in public in health would hide any information, nor could they,” says Dr. Joanne Langley, chair of pediatric vaccinology at Dalhousie University.Vaccines undergo extensive, rigorous testing for safety and efficacy. Through four phases of research and testing, it takes ten or fifteen years before a vaccine can be rolled out and given to the general public.

There are regulatory bodies, Dr. Langley notes, at every turn. “Everything we have to think carefully through …. And that’s happening at multiple stages, it’s happening by the ethics board that approved the studies, by the regulator that decides the studies that can be done and then evaluates the evidence, by the regulator that decides the studies can be done, and then evaluates the evidence when the authorization request is submitted, by every province that decides to implement it in their program, at the national level by the National Advisory Committee on Immunization that looks at the entire package of evidence for each vaccine,” says Dr. Langley. “None of the people I’ve just mentioned have an explicit conflict of interest in that they might materially benefit.”

Autism symptoms usually manifest in early childhood. The timing can coincide with vaccination, which may be why some people see a connection. “It’s mainly a disorder of the brain and our ability to interact, rather than physical disorders,” says Dr. Langley. While the cause is not yet known for certain, “I don’t think there’s any value to more studies on the incidence of autism after vaccines, we’ve spent so many human resources now,” she says. “There’s like 30 studies that show no link.”

The first shot

Katie Newcombe and her husband are sitting in her doctor’s Halifax office, looking into their baby’s car seat. Little Madeline is asleep, head on her right shoulder, a stripe of thin dark hair visible behind her ear. Madeline is two months old today – a milestone for the new family. It also means it’s time for her first vaccination.

caption

Katie Newcombe and her husband Robert await their daughter’s first vaccination.Newcombe, a management consultant, is eager to immunize her daughter. She’s been concerned by recent news of disease outbreaks and the anti-vaxxer backlash. “Having a newborn, and taking her out and about, it’s always in the back of my mind,” she says. Vaccines have “kept everyone healthy this long, and there’s a bunch of diseases and whatnot that no longer are running rampant because of vaccines, so I’d rather protect my child from them than take the risk. It seems like less of a risk to vaccinate her than to not.”

Madeline is assessed by a medical student. Then Dr. Gilda Bowdridge enters the room like a storm. “Today is baby day,” she says. She has seen two other infants already, vaccinating one, and it’s only 9 a.m.

caption

Madeline gets her first shot.Madeline sits on Newcombe’s knee, awake and looking around. With the skill of a thousand repetitions, Bowdridge swiftly injects the first shot into Madeline’s left thigh. Madeline gets fussy; she’s uncomfortable. But she will soon be immune to pneumococcal disease. Madeline is rotated, facing the other way. “This one, she will cry,” says the doctor, preparing the parents for the next needle. It goes into her right thigh. Madeline cries. She will stop crying soon, and she will also be immune to diptheria, tetanus and whooping cough. The whole procedure takes sixty seconds.

caption

Dr. Bowdridge debriefs Madeline’s parents after vaccinating their daughter.Dr. Bowdridge debriefs the parents: “It’s normal for her to be cranky, have a fever, and some feeding problems, and trouble sleeping.” She offers some children’s pain reliever in case of fever or soreness. Dr. Bowdridge leaves the room. Madeline’s father takes her out to the hallway to quiet her down. It’s calm in the office again. Newcombe stays behind for her own booster shot.

Recent outbreaks

Vaccination is a major step in medical history. “Vaccines are touted as one of the top ten public health achievements of the twentieth century,” says Elaine Holmes. The World Health Organization estimates vaccines prevent two to three million deaths a year. The measles vaccine alone prevented at least 21 million deaths from 2000 to 2017.

In recent years, vaccination rates have dropped. Canada and the U.S. have seen outbreaks of measles, a highly contagious disease causing fever, cough, rash and sometimes permanent brain injury or death. It was declared eliminated from Canada in 1998 and from the U.S. in 2000.

Measles cases have seen a global increase of 30 per cent. Nearly 1,000 children have died of measles in Madagascar since October. In the Philippines measles cases have increased 758 per cent. Outbreaks are happening in Italy, France, Venezuela, Ukraine and Japan. The WHO has declared vaccine hesitancy, as it is called, one of the top ten threats to health worldwide.

I think it’s really sad, and really unnecessary, that we had all this medical research and figured out a way to protect ourselves against it and then people are deciding that, no, that was a waste of time Katie Newcombe

In Nova Scotia, people generally comply with vaccination schedules at a rate estimated at close to 90 per cent. “We firmly believe that we don’t have a huge anti-vaccine movement,” says Elaine Holmes. “We would acknowledge that there are people in our population who perhaps have some reservations around immunization, but for the most part we feel we have a population that embraces immunization to protect not only themselves as individuals, but the population at large.”

To help meet the challenge of vaccination hesitancy, Communicable Disease Prevention and Control is starting a social media campaign promoting immunization, in response to recent measles outbreaks. “We have to really rethink how the public receives information,” says Holmes.

caption

Madeline enters the pool for the first time.The outbreaks have worried Katie Newcombe.

“I think it’s really sad, and really unnecessary, that we had all this medical research and figured out a way to protect ourselves against it and then people are deciding that, no, that was a waste of time.” Before her daughter’s vaccinations, Newcombe was nervous about taking her out. “Just having a newborn, taking her out to places, it’s always in the back of my mind.”

One week after Madeline’s appointment, mother and daughter are at the community swimming pool. She stares innocently at her mother’s face as she enters the water for the first time. Her eyes widen. Newcombe smiles as her daughter reaches another milestone.

C

Cinnamon

J

Joanne Miller

F

Frank dongle

A

Andrew Mader

F

Frank Wakefield

J

Joe dingle