The waiting game

caption

Long queues, a kind stranger and the mysterious Dr. Andrew. A night at a Halifax emergency department

Ken Kelly is charming. He exudes a kind humour that is alien in the languid air of the holding room of the emergency department at Halifax’s Queen Elizabeth II Health Sciences Centre. In a stream of hunched shoulders and demoralized faces, he stands out. People sit in the chairs across from him and close their eyes, as if willing time to speed up. He asks each one how long they’ve been waiting and how they’re feeling.

In his lap sits a folded up piece of paper with a pen clipped to it. On it, he jots down the names and topics of conversation he has with people he has come across that night. He refers to it when he talks about people he has met, double-checking names and little details, almost as if it would be disrespectful to make a mistake.

He had come from Ash Wednesday mass that night, the faint smudge on his forehead barely visible at the late hour. His voice cut through the uncomfortable stillness in the room.

“You almost need an icebreaker,” Kelly, 69, recalls later, his smile somehow evident through the phone.

That night, he told every patient he spoke to that he hoped they would get the “tall Dr. Andrew,” the nice doctor who is ever so helpful.

caption

Ken Kelly spoke to every person who went in and out of the waiting room that night with a smile on his face.Kelly was not feeling well for about a week and finally decided it was time for a trip to the emergency department. Later that night, he was told he had heart arrhythmia, a condition that causes irregularity in heartbeat.

He was at the hospital for about seven hours that night.

He is now scheduled for cardiologist appointments to treat his condition and he’s still seeking treatment options. This, however, does not stop him from volunteering every week to serve food to the underprivileged at the St. Mary’s Basilica.

Code Orange

Everybody seems to have an emergency horror story. A long wait in pain in some waiting room somewhere with fluorescent lights and leather chairs that are just a little too uncomfortable for hours of habitation. Patients wait far longer than the times the guidelines dictate for emergency care, from 15 minutes to two hours. Many are braced for the long wait: they come equipped with laptops, knitting and books.

Recently, Cobequid Community Health Centre in Lower Sackville had to remain open past its midnight closure time to care for patients who needed to be hospitalized but couldn’t be, because of a lack of beds. That’s what it comes down to: a rocky flow and a huge clog that sits in one’s memory, darkening their view of the health-care system. In mid-March, nurses at the Halifax Infirmary emergency department called for a Code Orange, a code usually reserved for events with mass casualties, but their request was denied. The Nova Scotia Government and General Employees Union stated there were three fewer nurses working in the emergency department than were required, and 99 patients waiting to be seen.

But the frustration does not end in the waiting room. The fight for attention runs throughout the entire emergency department of the hospital, deeply ingrained in the DNA of a system that is heavily relied upon.

Hunting for space

For Dr. Sam Campbell, every day is a never-ending search for space. He has been working in Halifax as an emergency physician since 1996 and his passion for his work is palpable. He walks through the maze of pods, little sections in the department, with purpose and determination. His stride is brisk and anyone else would have to jog to keep up with his long legs. It is easy to see why he is an emergency doctor.

He marches through hallways filled with patients waiting for beds, taking sharp turns into other hallways filled with more patients and more waiting. Around him are stretchers, each with a patient and equipped with its own paramedic, who is unable to leave until the patient has been admitted. This, he says, is not unusual. The union for Nova Scotia paramedics said earlier this month that paramedics are overworked and exhausted, partly due to long waits to hand over patients. The Nova Scotia Health Authority is working on a policy to set time limits for offload times for ambulances.

“It’s like a swimming instructor who goes to the swimming pool but they’ve drained all the water out,” says Dr. Campbell. “So you’ve got the swimming pool but you can’t use it.”

Simply put, there are too many swimmers and not enough water.

Emergency departments are no longer being used as emergency departments. They have become an extension of other hospital facilities, with patients staying past their emergency needs. This jams the whole system: patients cannot be moved fast enough to where they need to go. Emergency doctors and physicians are left to make do with what they’ve got and usually, it’s not enough.

When it comes to treating patients, Dr. Campbell says, “you’re not choosing the right thing, you’re choosing the least wrong thing.”

Nova Scotia’s emergency wait times are similar to Ontario’s. However, Nova Scotia’s health authority has been implementing ways to increase efficiencies in emergency departments. A part of these plans has been giving nurses the power to send patients for electrocardiograms, also known as EKGs when a patient comes in with chest pain. This means that when the patient is then seen by a doctor, the doctor already has the test results, speeding up the process.

Dr. Campbell takes his opportunities when he sees them: any bed on the floor is fair game for him to treat patients. It’s a never-ending battle. He looks at a screen in the hub of the pod and lets out a humourless laugh. A patient has been waiting nine hours with chest pain and has yet to be seen. He says he will probably see him in Pod 5, despite the fact that he should be treated in different pod with more monitors. There just isn’t any space.

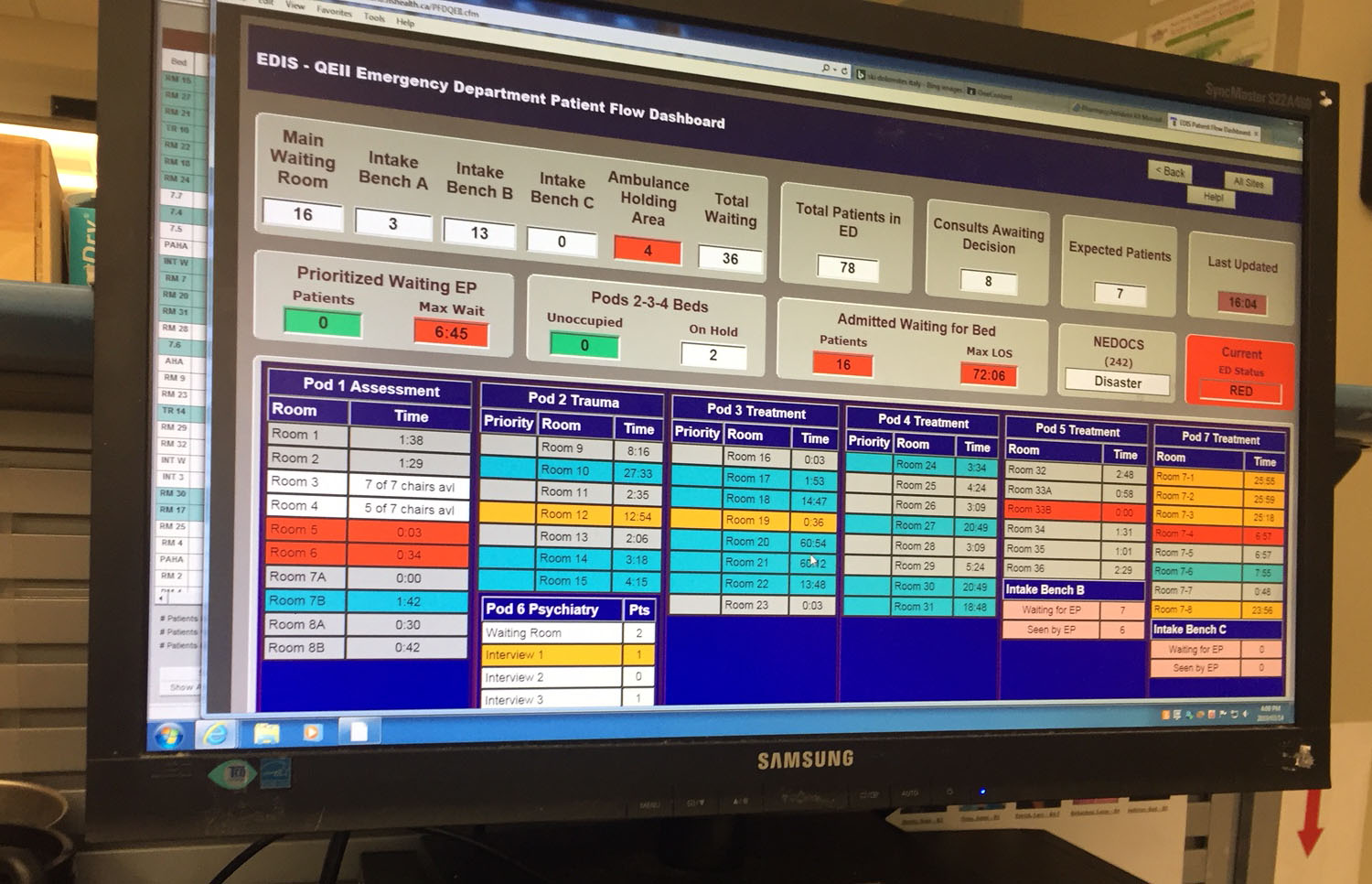

caption

Dr. Sam Campbell looks at the spreadsheet that shows how long patients have been waiting to be seen at the emergency department.Who’s seen first?

The Canadian Triage and Acuity Scale, more commonly referred to as CTAS, is the measure used to determine the order in which people are seen by physicians. Upon arriving at an emergency department, patients are first seen by a triage nurse. The nurse speaks to them, checks their vital signs and assigns a CTAS score.

The scale runs from one to five: from resuscitation (one) to non-urgent (five). Five would be symptoms such as a sore throat, or a simple suture – a patient who could wait for two hours to be treated. Level four is “less urgent” and would include things like a sprained ankle: something that needs medical attention but is not life-threatening. The timeline for a person under CTAS four would be seeing a physician within an hour.

The third, “urgent,” is slightly more tricky: illnesses that are not life-threatening but could become life threatening. Level three patients must be seen within 30 minutes based on the guidelines.

Level two is “emergent” and patients who will absolutely become more ill if they are not treated. An example of this is chest pain or signs of stroke. These patients should be seen within 15 to 30 minutes of being triaged.

And last and most serious is level one: resuscitation. These are patients, in most case arriving by ambulance, who are unresponsive and in life-threatening danger. Obviously, they require immediate care.

These times are the national standard, but the reality does not match up.

“I would argue that there’s probably not a lot of facilities across the province who are meeting them,” says Tanya Penney, senior director for the emergency and critical care programs at the Nova Scotia Health Authority. “But I would also argue that just because you can’t meet the standard doesn’t mean that we should change the standard.”

“It means that we always need to be working towards the standard.”

An 11-hour wait

Amanda Beaver was a CTAS 3 patient. She was a like a veteran of the waiting room that night. People around her would tell you she had been there for 11 hours, as if she were a cautionary tale. A “turn back if you can” sign. Beside her sat a frustrated teenage boy. He periodically got up to talk to the nurses, asking each time how long it would take for his mother to be seen. They didn’t know.

She sat in the corner on a leather chair, her feet propped up on another chair facing her. The dark circles under her eyes stood out against her sallow skin. She rarely talked. To her right was a decorative fireplace filled with white stones. It provided no heat. The tepid air in the room filled with excited energy as a nurse with a clipboard walked in from behind glass doors – everyone knew the nurse is about to call a name. Some told Beaver they hoped it would be her name. Eleven hours in, a nurse finally did call her name. Patients around her filled with hope: they could be next.

Later that night, she was told she had severe dehydration and mild kidney failure.

“I didn’t really feel the pain in my kidneys. I think it’s ’cause I was just feeling so miserable and I was adapting to it,” Beaver said later. “I just, I felt very, very sick and just very weak.”

She recalls Dr. Andrew, the heroic doctor with the glowing reputation, apologizing to her for the wait.

Beaver and the rest of the beleaguered patients didn’t know what was happening on the other side of the glass walls: physicians and nurses scrambling to find a somewhere, anywhere, to put them.

caption

Number of people waitings for beds and the number of people in different pods of the department is displayed on the computer screen.Physicians feel almost helpless. The problem is out of their control: they cannot move a patient to another hospital department to free up a bed until the patient has someplace to go.

“My job here is to see these patients and I won’t see a single patient in an emergency bed today,” says Dr. Campbell. “I’ll see them in a hallway or a family room or pod 5 because we have no beds.”

Pod 5 is a the place with people with a CTAS score of 5 are taken. It’s designed for quick fixes: a couple of stitches here, a cast taken off there. It is not equipped for patients with more serious conditions, such as chest pain. Yet Dr. Campbell finds himself having to treat more and more patients in the area simply because it’s better to see them somewhere than not at all.

What is desperately needed are long-term spaces for patients to be moved to for the department to move like a well-oiled machine.

Last night I felt as though I’d been beaten up. It’s absolutely soul destroying.Dr. Sam Campbell

Dr. Campbell believes that until other departments can feel the pressure of the lack of beds, nothing is likely to change. If someone has 10 in-patient beds but there are 15 people that need that bed, there is no pressure on the department to empty beds or find an alternative place to put those patients.

The burden of long-term care for the extra five people is placed on the emergency department.

“They’ve had any kind of evolutionary pressure to adjust the system removed,” says Dr. Campbell. “They don’t have to fix the system, they don’t have to be more efficient, they don’t have to advocate for more beds, it’s just easier for them to say, ‘sorry, we’re full’.”

Penney, citing the most up-to-date statistics, said 90 per cent of the time patients who came into the emergency department at the Halifax Infirmary and needed to be admitted, waited for 37 hours to be moved to an inpatient bed or to another area of the hospital. This is from the time they were triaged to the time that they are moved out of the emergency department to another bed.

“It starts to decrease your capacity for things that are outside of your control,” says Penney about the long inpatient admission time.

caption

Ken Kelly spends every Wednesday helping serve food at the St. Mary’s Basilica Church at Spring Garden and Barrington.The accountability is placed on emergency department staff who have zero ability to fix the problem. They are left on most days with less than one-third of their beds available, because the rest are occupied by people who are no longer in an emergency or require emergency care.

It is not just the area that is ill-equipped to care for patients past their emergency needs, but the physicians, too. Physicians and nurses in emergency departments are specialized in emergency medicine: they have little knowledge about long-term or primary-care issues.

“People still somehow think that an emergency physician is a doctor is a doctor is a doctor,” says Dr. Campbell.

This system takes a toll on everyone it touches: doctors are left exhausted and frustrated, nurses often burnout, patients give up and leave, often after half a day, with bad memories and their own emergency story.

“Last night I felt as though I’d been beaten up,” says Dr. Campbell. “It’s absolutely soul destroying.”

Kelly tells his story later with a few laughs and many honourable mentions of Dr. Andrew. Unfortunately, his emergency story is not quite at an end. It isn’t one of just horror and frustration, either. Kelly tells tales of patients past who have had it worse: the one with strep throat – incredible young woman, he says, who was raised by two deaf parents. Or the nice man who had been coughing up blood but wasn’t seen for hours. Kelly says he had started to worry about him. And did anyone else meet the sweet mother and daughter who had been there earlier?

Kelly sits and Kelly talks and Kelly brings a tiny reprieve in a gloomy day.