The Affordability Crisis: Can young people afford to live in Halifax?

caption

Young people protest the high living wages in Halifax.

Haligonians in their mid-to-late twenties are struggling to make a living in a city deemed one of the most unaffordable municipalities for young people, according to interviews with experts and data analysis by The Signal.

Halifax, the country’s second-fastest growing city and widely known as a university town, has the fifth-highest proportion of young people aged 15 to 29 out of 35 Canadian cities, according to an analysis of Statistics Canada data.

Nova Scotia has the highest poverty rate and young people pay among the highest prices for food and rent, while living in a situation described as “energy poverty.”

But it doesn’t end there. Related stories

Young people experience increasing instances of evictions and are turning to food banks in growing numbers, resulting in heightened anxiety that is so bad it is now being studied by experts, according to interviews conducted by The Signal.

Jasper Lennox, 23, is a full-time customer service worker who grew up in Bedford whose minimum wage income is not keeping up with the cost of living.

They and their partner have considered moving to cities like Montréal or Calgary.

“I would like to move somewhere else that’s more affordable, I really would,” Lennox said, “but I don’t think I can afford the moving expenses.”

Christine Saulnier, director of the Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives’ Nova Scotia branch, understands Lennox’s desire to leave.

“It’s not attractive for young people to stay here,” said Saulnier, who has calculated the difference between a living wage and minimum wage.

“I don’t think we as a society really understand. You’re coming out of an undergrad [degree] with an expectation for what? A minimum wage job?”

The plight of young people was highlighted last year in a survey of 28 municipalities that looked at affordability for people between the ages of 15 and 29, the so-called Affordability Index.

Robert Barnard, co-founder of the Calgary-based Youthful Cities, says the index his organization created challenges the notion of an “East Coast discount” that assumes Atlantic Canada is cheaper than the country’s larger regions.

“We have information to say that there’s no such thing, certainly in Halifax, it’s a really expensive city for young people to live in,” Barnard said in an interview with The Signal.

Housing and energy costs are hitting young people hard

According to Kelvin Ndoro, senior analyst for the Canadian Mortgage and Housing Corporation (CMHC), Halifax student housing is in dire straits.

“In the context of Halifax what I see as the key issue is the lack of on-campus student housing … you’ll see that vacancy rates are lowest in student-dominated areas, such as South End, Halifax … it tends to push rental prices up,” says Ndoro.

In addition to housing costs, young people also have to make changes when it comes to home energy costs.

“I’m sure many students already do this, you turn down the thermostat and turn it down, down, down. You turn it down so you’re paying less for it,” says Larry Hughes, a Dalhousie University electrical and computer engineering professor who studies energy affordability.

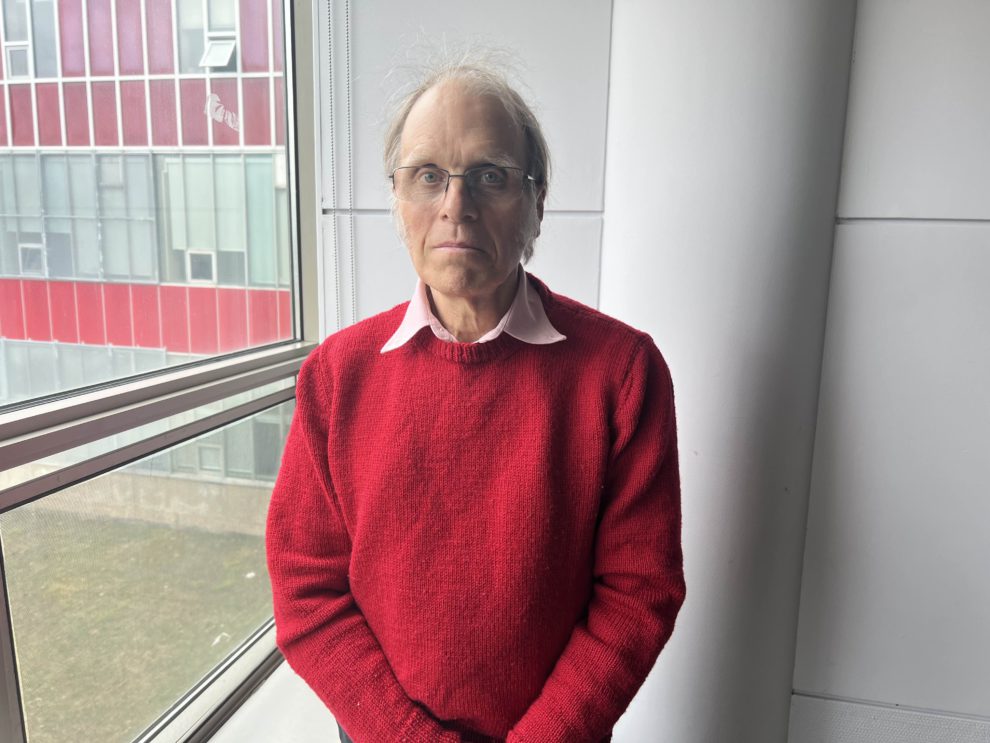

caption

Larry Hughes, a Dalhousie University professor of electrical and computer engineering, studies energy poverty and affordability. Photo: Sam FarleyBased on the latest data from Statistics Canada, in 2019, households in the Atlantic region spent nearly twice the national average on home electricity.

An Oct. 18, 2022, briefing note to the Natural Resource Canada’s deputy minister, obtained through an access-to-information request, says that “affordability is a foremost concern of provinces in a region that has among the highest electricity rates and greatest incidence of energy poverty in the country.”

The federal department says households living in energy poverty spend more than 10 per cent of their income on energy costs. Across all income brackets, the Atlantic Canada region experiences energy poverty at rates double or more than the national average.

A spokesperson for Natural Resource Canada said in an email the region’s rates of energy poverty were based on high energy prices, reliance on inefficient forms of space heating, and relatively low incomes.

Hughes says that for renters in older, less efficient buildings, energy costs will be higher. “It’s going to cost the landlord a whack of money and the landlord would probably turn around and say next year or next month, your rent’s going to have to increase to cover the fuel cost.”

Kevin Russell, executive director of Investment Property Owners Association of Nova Scotia, an organization that represents landlords in the province, said in an email statement that most apartment leases include heat in the cost.

“Therefore, any increase in energy costs would flow into the rent no different than any other increases in operating costs. But this is not occurring because of the two per cent rent cap,” Russell said.

The rent cap was put in place in November 2020 to help tenants during the height of the COVID-19 pandemic. It was extended in February 2022 to December 31, 2023, and in January 2024 the rent cap will increase to five per cent.

It’s not just tenants experiencing increased costs from energy. Russell says that next year many landlords “will not earn sufficient rental income to cover the increased cost … Most small [landlords] are in negative cash flow.”

Food banks struggle to keep up with growing client base

caption

Saint Mary’s University Community Food Room volunteer Sofia Amaya says the service’s food stock is depleting. Photo: Jake WebbFuel costs are not only affecting housing. Sylvain Charlebois, director of the Agri-Food Analysis Lab at Dalhousie University, says “problems with energy logistics and fuel costs” are factors causing Halifax’s food price to rise.

“Housing is really impacting food affordability as well,” Charlebois says. “You have less money to spend on food.”

Charlebois worked on Canada’s Food Report 2023 with experts across the country. The report forecasts that Nova Scotia’s price for food will rise higher than last year’s increase of 10.5 per cent. This has forced more Nova Scotians to use food banks.

Food Banks Canada released the HungerCount report in 2022, and it showed there were 27,526 total visits in Nova Scotia, 14 per cent more visits than the previous year.

Nova Scotia has the highest food bank usage in Atlantic Canada.

Parker Street Food & Furniture Bank is located in Halifax. Brigitte MacInnes, the client services director, has noticed a major increase in Parker Street’s clients. Since 2022, there was a 3.8 per cent increase for adults, and a 20.9 per cent increase for children.

“For the age group in late teens and early twenties, a lot of that age group might be in university, they might be in college,” says MacInnes. “Most universities are providing food services.”

Dalhousie, Mount Saint Vincent, and Saint Mary’s all have food services for its students. The SMU Community Food Room is located in the Student Centre on the fifth floor.

The Food Room’s number of clients grew to 178 in February from 86 last September– an increase of 107 per cent. Kara-Lyne Shaw, the Food Room co-ordinator, says Feed Nova Scotia used to do a bi-weekly order for the Food Room. Because of how high demand has become, that order is now weekly.

All of these high prices, from housing to food, are taking a toll on the well-being of young adults across Nova Scotia.

Tracking wellbeing

Ian Munro, the chief economist of the Halifax Partnership, an economic planning organization, said there is a tie between affordability and well-being. In his work, he’s found the biggest issues Haligonians face revolve around affordability, specifically with housing.

“So that, clearly, is going to affect a lot of people’s well-being,” he said.

As for young people, Engage Nova Scotia, which tracks well-being indicators in Nova Scotia, found young adults between the ages of 15 and 34 are roughly twice as worried about their finances compared to the provincial average.

The same group said it is dedicating nearly twice as little time for its own well-being — such as exercising or eating healthy — compared to the provincial average.

With rising costs and other economic frictions, young people are more prone to feeling the impact of these costs. That’s according to Bryan Smale, the director of the Canadian Index of Wellbeing, a leader in tracking dozens of well-being indicators across Canada and an advisor for the federal government’s new Quality of Life Framework launched in 2021.

Being exposed to economic downturns at a vulnerable time in their lives, Smale said, has an impact on the well-being of young adults.

“They are thinking, “Will I ever own my own home? “Will I ever have the kind of job that I love?”

How is the province helping young people?

caption

Premier Tim Houston talking to reporters at Province House after the provincial budget meeting on March 23rd. Photo: Crystal GreeneJoanne Hussey, a community legal worker at Dalhousie Legal Aid Service, says that the provincial government has a responsibility to bridge the gap between minimum wage and high rent prices.

“We need to keep the rents lower, or we need to increase wages, or we need to do both,” she said in an interview with The Signal. “People are becoming homeless purely for economic reasons.”

Over the last 30 years, many cities “rebuilt their cores in a way that was very appealing for young adults,” said Karen Chapple, director of the University of Toronto’s School of Cities.

“When you do all those improvements, when you invest in all these different ways, you also raise land values, and you make housing very expensive.”

“It's not just some Toronto problem, but it's something that the whole country needs to deal with,” Chapple said.

Meanwhile, the wages of Nova Scotians have not kept up with these increased living costs.

In February, Nova Scotia’s minimum wage review committee recommended an accelerated increase to the minimum wage “due to the unforeseen and significant increase in inflation for the 2022 calendar year - and what is now forecast for the 2023 calendar year.”

After the provincial budget was tabled on March 23, Premier Tim Houston spoke to reporters.

The Signal asked Houston what happens if young people under age 30 continue to get priced out of HRM and what the government was doing about it.

“We'll continue to invest in ways to make sure that life is affordable for Nova Scotians … I think Nova Scotians under 30 in this province have a very unique benefit and I'm not aware of any other jurisdiction that has it,” said Houston, pushing back against suggestions that the city is unaffordable for young people.

The premier referenced the expansion of a program which returns provincial income tax for tradespeople and nurses on their first $50,000 if income.

During the question period, Suzy Hansen, the Nova Scotia NDP housing critic said, “we were sorely disappointed by a budget that doubles down on the approach of funnelling public money to private landlords through more money for rent supplements, which will certainly help … but will certainly not build new, affordable, non-market housing units.”

Meanwhile, Houston said the solution to the housing crisis is more housing and that there are investments in affordable housing in the budget.

“Those types of investments, they're working … we're looking to the future of this province,” Houston said.

Young people struggling to get by in Halifax may have a different opinion.

Editor's Note

The Affordability Crisis series is in response to the Real Affordability Index by the Youthful Cities. The index named Halifax the least affordable city in Canada by examining a variety of different factors: income, housing, and more.

The Signal conducted its own investigation that led to the conclusion that Halifax is still one of the least affordable cities in Canada. The main story seen above provides a broad look into these issues, so that readers can understand the many different aspects of what makes Halifax so expensive.

.

About the author

Luke Dyment

Luke Dyment is a Halifax-based reporter from Prince Edward Island. He has written for the Globe and Mail, The Signal and the Dalhousie Gazette....

Sam Farley

Sam is a fourth-year King's journalism student from Boston.

Crystal Greene

Crystal Greene (she/her) is originally from Winnipeg, where she lived most of her life. She now lives in Kjipuktuk/Halifax with her toddler....

Andrew Lam

Andrew Lam (they/she) is a Chinese and trans journalist interested in labour, LGBTQIA+, and political stories. They hope to leverage their data...

Jack Ronahan

Jack is a fourth year journalism student at the University of King's College.

Jake Webb

Jake Webb is a fourth-year student in the Bachelor of Journalism (Honours) program at the University of King's College.

David Shuman

David Shuman is a reporter from Musquodoboit Harbour, NS. He works as the editor-in-chief of the Dalhousie Gazette, Dalhousie's independent campus...