Young adults in Halifax struggle to not only take care of the bills, but themselves

caption

Dalhousie University student Laura Colford holds a pair of jeans she made in her upcycling class. This is one hobby she has to take her mind off the stresses of being a young adult in Halifax -- not only school but affording to live in the city at all.Worsened by affordability crisis, several quality-of-life indicators show young Nova Scotians scoring lower

Laura Colford has a lot on her plate. The 19-year-old works two jobs and volunteers, in addition to attending classes at Dalhousie University.

“I’m definitely stressed at times,” she said in an interview with The Signal about an hour before a class on March 29. Exams are approaching. She’s overwhelmed. Anxious about a study session she has planned for later that day, she eyes the library from across the sunny, bustling campus during the interview.

But it’s not just maintaining good grades that has Colford nervously fidgeting with her hands or laughing off her long list of responsibilities. It’s also her concern about the next month’s rent and rising grocery bill she faces as a resident in one of Canada’s most expensive cities for young people. This is according to The Signal’s analysis of Statistics Canada data and interviews with experts who study the stresses and challenges plaguing this age group.

Colford understands how the stress of those increasing expenses affects her health, the field she studies. But most importantly, she’s living with those challenges every day.

Laura Colford is busy as a full-time Dalhousie University student with two jobs. That doesn’t leave her much time for herself or other activities — a growing problem among young adults in Halifax and across Canada. However, she has found ways to care for her well-being.

Colford is one of many Nova Scotians between the ages of 15 and 34 struggling with maintaining a good work-life balance, living a healthy lifestyle and engaging with community — a combination experts call well-being.

Tracking stress

An increasing number of organizations, including StatCan, are tracking the well-being of people like Colford.

The non-profit research group Engage Nova Scotia found young Nova Scotian adults struggle the most maintaining a sense of well-being.

While most of this research was conducted before the pandemic, Engage Nova Scotia researchers said the findings that place young people low in the categories that measure well-being remain relevant.

StatCan has also tracked well-being characteristics since the mid-2010s. The agency’s primary approach is asking people how they perceive their health, mental health and life satisfaction through its community health survey.

A StatCan spokesperson said the organization decided against asking similar questions for the 2021 census. The consideration was part of the agency’s efforts to better measure well-being indicators.

The federal agency found in a 2022 study that out of all adult age groups, those aged 20 to 29 experience lower perceived well-being. The Signal analyzed those well-being factors in StatCan data, finding conclusions similar to Engage Nova Scotia’s. (This link takes you to a Google sheet that breaks down key results)

For instance, Canada’s young adults rate their perceived mental health and sense of community belonging lower than older adults.

Bryan Smale is the director of the Canadian Index of Wellbeing — an organization, like Engage Nova Scotia and StatCan, tracking the quality of Canadian lives. He stressed one’s overall well-being is never determined by a single factor, but by how many “different domains in our lives” are connected.

But affordability is “strongly associated” with one’s well-being. Bearing the brunt of the economic downturn, Smale said, has an impact on the well-being of young adults.

“They are thinking, “Will I ever own my own home? Will I ever have the kind of job that I love?”

If someone cuts back on buying food because they’re short on money, it’s likely they’re cutting back on other needs as well, said Patty Williams, a professor of applied human nutrition at Halifax’s Mount Saint Vincent University. That “material deprivation,” in turn, takes a toll on one’s overall health.

While Colford remains stuck in a stressful cycle of rising rent and grocery bills — and much of her time is tied up with work and school — she still finds time a few hours a week for her favourite hobbies like reading and dancing, which help her to manage her stress. Recently, she’s taken classes in upcycling — fixing old, worn clothes into something new.

“It’s easy to get trapped in the mindset of ‘[Work] is the only thing that’s important,’ then pushing your well-being aside,” she said. She’s fallen into that trap of unhealthy work habits, then excess stress, before — especially during busy times of the year like this.

caption

Colford holds a jacket she made in her upcycling class. This is one hobby she has to take her mind off the stresses of being a young adult in Halifax — not only school but affording to live in the city at all. (Luke Dyment)

Government responses

As the tracking of well-being in Canada gains momentum, federal, provincial, territorial and municipal governments have taken notice. Using a similar framework as the Canadian Index of Wellbeing and approaches of other countries, the Department of Finance developed a quality of life framework in 2021, intending “to better incorporate quality of life measurements into decision-making and budgeting.”

In the Department of Finance’s recent budget, a “quality of life impact” was assigned to each of the measures. For instance, a new grocery rebate in the budget was assigned a “prosperity” impact, signalling the rebate would improve well-being by enhancing financial security.

caption

(Department of Finance)

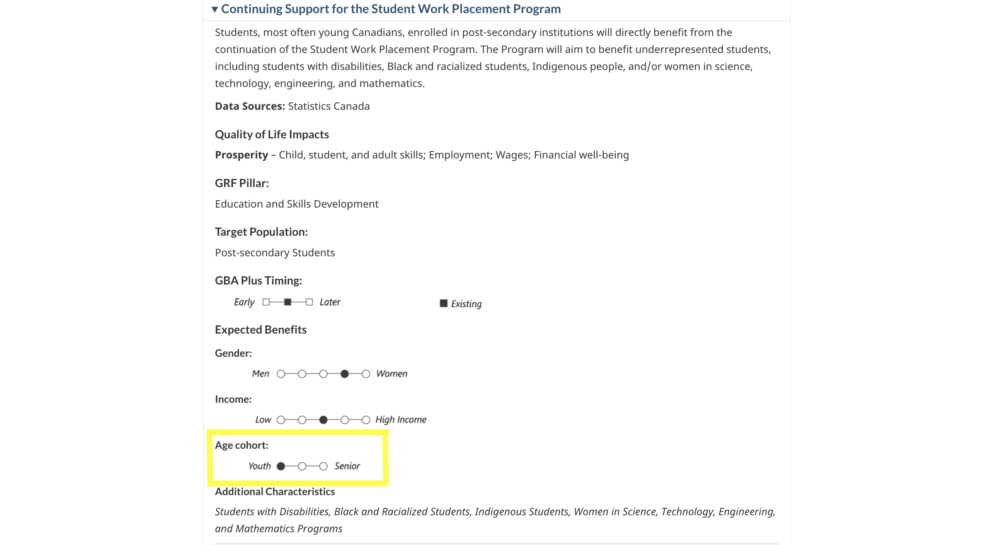

Part of this assessment includes a predicted impact according to age. Many of the budget measures focusing on support for students indicated a “youth” age cohort, pointing out that young people are the intended beneficiaries of the action. Outside of student-focused supports, few of the budget measures target exclusively young people.

caption

(Department of Finance)

When contacted by The Signal for comment on how budget measures such as the grocery rebate will help young Canadians, the Department of Finance didn’t elaborate beyond what was provided in the budget.

Susan LeBlanc, an MLA and the Nova Scotia New Democratic Party’s health critic, discusses the importance of healthy living and how the provincial government can improve it.

Individual well-being is also starting to be taken more into account in Halifax. In fact, the city’s five-year economic plan approved in 2022 lists improved well-being for all age groups as one of its top three goals.

A report prepared for the city’s economic development committee found many residents and communities haven’t benefited from the city’s gross domestic product and population booms since the mid-2010s. With measures such as annual GDP not always tracking who benefits from economic growth, the well-being focus has become necessary.

As part of Halifax’s economic planning, Halifax Partnership — an organization that gathers data on local people and the economy — has started to track well-being indicators in the city. Its most recent survey found young people rate Halifax lower than older adults as a place to live or for recreation.

Colford can relate to those findings. She said that even compared to last year, it’s more difficult for her and her three roommates to make ends meet. At times, the stress of school, plus working two jobs just to pay the bills, has been isolating. That’s something she knows, as a health promotion student, isn’t good for her well-being.

But recently, Colford made a positive change: she takes a day off. Each Sunday, she avoids most work to focus on rest and her hobbies. She said it’s been an effective routine for breaking up stressful work and school cycles — like the one she is currently in during exam time.

“[It] takes the mind off of all the work and stress and everything,” said Colford. “Because once Monday starts, you know it’s work all over again.”

This story is part of a series in The Signal examining how and why Halifax is one of the most unaffordable Canadian cities for adults under 30 years old. Poor well-being is, according our research, a byproduct of the inability to cover basic expenses such as food and rent because of low wages.

About the author

Luke Dyment

Luke Dyment is a Halifax-based reporter from Prince Edward Island. He has written for the Globe and Mail, The Signal and the Dalhousie Gazette....