More young Haligonians are challenging landlords amidst a ‘housing crisis’

caption

A new group called the Dalhousie Mutual Aid Society marched from the university to Province House, where the Nova Scotia government reconvened its spring legislative assembly on March 21, 2023. They were protesting for more rent control.With a one per cent vacancy rate in Nova Scotia, people often have nowhere to go once evicted

Clark Barrie has been living in a three-bedroom apartment, with a roommate, on Quinpool Road in Halifax since May 2019. In January, their new landlord served them with a notice to vacate.

“We tried to mediate at the beginning and he [the landlord] was like, ‘I’ll give you one month free rent for you to find a place,’ … we’re low income and we’re in a housing crisis so there’s no way that we could find a place in one month,” said Barrie, 27, a full-time esthetician student who cleans houses on the weekends.

With a low, one per cent vacancy rate in Halifax, the roommates decided their only option was to challenge the landlords’ notice through the Residential Tenancies Program.

In March, the roommates won their Residential Tenancies hearing, a process that tenants and landlords use to settle rent disputes.

But, their relief was cut short when their landlord Jaden Lawen,19, served them a notice of appeal to small claims court. Court documents obtained by The Signal state that Lawen believes that residential tenancies officer Julie Tapp “erred” in her decision and that it’s “within his rights” as a landlord to “take occupancy.”

Lawen said the eviction was “due to personal circumstances he does not wish to disclose,” and justified the action as being the “most economical option.”

Barrie is part of a growing trend of young adults, under age 30, in Halifax challenging their landlords through Residential Tenancies hearings. Being evicted in a market with a one per cent vacancy rate is making it next to impossible to find housing.

caption

Clarke Barrie (third from right) and their band ENBY during a 2022 interview with The Signal at Barrie’s apartment.Rental market trends

Barrie’s eviction fight represents a trend involving young tenants Joanne Hussey is studying. The community legal worker for the Dalhousie Legal Aid Society, who represents clients in cases similar to Barrie’s, told The Signal that her office has been analyzing small claims court documents and has found an increasing number of tenants fighting evictions.

“What has changed significantly is the number of applications being made by tenants,” said Hussey. “Previously you had landlords making most of the claims … we can assume are to address issues with tenants, now we’re seeing more and more tenants challenging those … that speaks to the situation we’re in, the rental market right now, people just don’t have anywhere to go.”

Hussey has noticed that about a third of her organization’s clients are in their 20s. “If you’re in school, you do have access to student loans … there’s a bit of a lifeline there for people. Once you graduate, that isn’t the case, I think people making that transition to work have really struggled.”

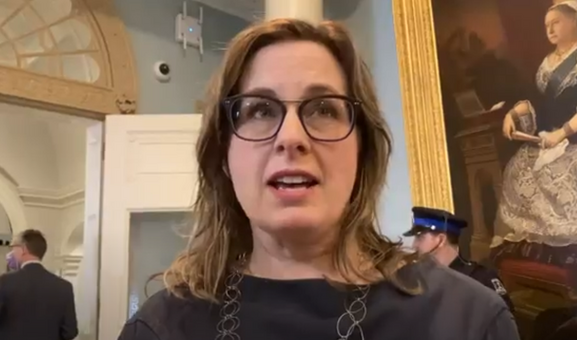

caption

“It’s not uncommon for us to see folks in that 15 to 29 group who are being evicted,” said Joanne Hussey, a community legal worker for the Dalhousie Legal Aid Society that represents clients at Residential Tenancy hearings. March 21, 2023. Photo: Crystal GreeneIn March 2023, Nova Scotia saw an 8.8 per cent increase in the cost of rented accommodations compared to the same period in 2022, the sharpest jump of any province or terrirtory and higher than the 5.3 Canadian average, according to an analysis of Statistics Canada’s Consumer Price Index.

.

In Halifax, the low vacancy rate is helping to push rental prices up. As is the increasing number of investors buying new condos. According to The Signal’s research of StatCan’s 2020 data that tracked investments in condominium apartments, investors bought almost 40 per cent of the units built between 2016 and 2020 in the city. The analysts who compiled the data told The Signal that these investors are also putting upward pressure on rents.

The high cost of living and low wages are pricing young people like Barrie out of the Halifax peninsula, into more suburban areas. According to Canada Mortgage and Housing Corporation, the average cost of a studio in the Halifax CMA jumped by 8.9 per cent, from 2021 to 2022.

One bedroom units increased by 7.6 per cent, and two bedrooms went up by 8.3 per cent in the same time period. StatCan data shows that 14.4 per cent of people aged 25 to 34, Barrie’s age group, are paying beyond CMHC’s guideline of what’s considered to be affordable housing, which is no more than 30 per cent of one’s gross monthly income.

Halifax the unaffordable city

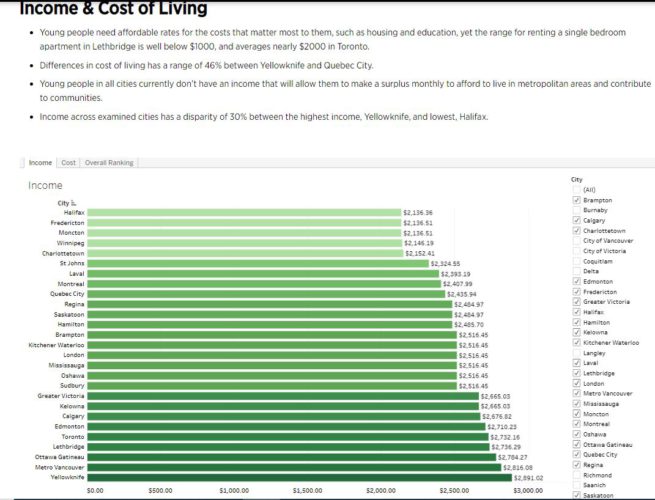

The unaffordability of life in Halifax for young people under age 30 was flagged last year in what’s called the Youthful Cities Real Affordability Index. This index tallied expense indicators such as rent and housing, and then subtracted the amount from an average monthly income of $2,136.36. The result was an average monthly deficit of -$1290.74 - the highest in Halifax compared to 27 other municipalities including Vancouver, Toronto and Montreal.

caption

Halifax scored the highest in the income & cost of living calculations in the Real Affordability Index by Youthful CitiesAccording to an analysis of customized StatCan data obtained by The Signal, Haligonians aged 20 to 29 are ranked 33rd for the lowest average wage, at $22.23 per hour, out of 36 major Canadian cities.

Nova Scotia’s minimum wage is $14.50 per hour, whereas a living wage in 2022 was $23.50 according to the Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives.

The Signal’s analysis of data and interviews confirm Halifax continues to be one of the least unaffordable Canadian cities for 20-somethings like Barrie.

“I’ve never been so stressed, I just lost a cleaning client … I’m like paycheque to paycheque, I can barely afford to eat,” said Barrie who counter-served their landlord in March to fight his eviction notice. “That [form] cost me $30 I couldn’t afford, we’re very overwhelmed.”

caption

Jaden Lawen (right) and his father Louie Lawen (left), during a trip to Lebanon. Photo: Crystal GreeneBarrie’s landlord is director and vice-president of Newal Property Investments Ltd. He is known for his mutual aid campaign Halifax to Beirut with Love, which raised more than $100,000. He is a second-year engineering student at Dalhousie University and is the son of Louie Lawen, who is the CEO of the Lawen Group, which includes Dexel Developments and Paramount Management, together owning 2,000 residential units and 300,000 square feet of commercial space in Halifax.

A complex problem requiring solutions

Advocates and politicians who spoke to The Signal said there is a need for more housing stock to alleviate the “housing crisis.”

caption

'For rent' signs are a rare sight in Halifax. This one was spotted at the corner of Robie and Cunard Streets in the North End on March 21, 2023.“In the context of Halifax, the key issue is the lack of on campus student housing that affects the broader rental market,” said Kevin Ndoro, a CMHC senior analyst, referring to the approximately 35,000 post-secondary students in the city, of which only 20 per cent are living on campus.

“When you look at CMHC rent data, you’ll see that vacancy rates are lowest in student-dominated areas, such as South End; it tends to push rental prices up.”

Ndoro believes that the rise of condominium developments is a good sign as the existing rental stock will get freed up for low- and middle-income earners, and the highest paid will move into condos. He said it will lower the one per cent vacancy rate in Halifax.

caption

A new condominium development is being constructed at the corner of Robie and Almon Streets in Halifax's North End. Advocates say there is not enough affordable housing being built, and are concerned that the new buildings are targeted for those with a higher income. March 21, 2023.“Everything that a developer has to pay in taxes, the fees that Halifax piles on a development, you can’t build affordable housing in Halifax,” said Kevin Russell, the executive director for the Investment Property Owners Association of Nova Scotia (IPOANS), which represents landlords.

Russell said that affordable housing developers are spending $350,000 per new home. Private sector developers’ costs are $400,000 to $500,000 per new home. “It’s tough, it’s a complex problem, and if we could build affordable units, they would be built,” added Russell.

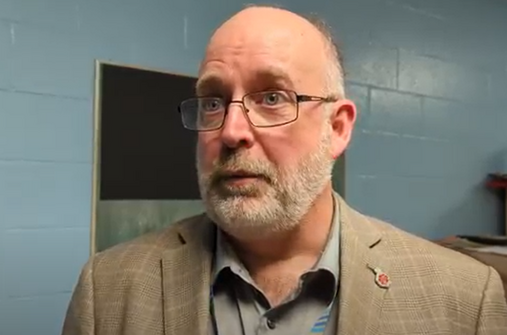

caption

"Business 101 is you can't have expenses outstripping revenues ... this is what's happening in the small rental property market, is that most of them are in negative cash flow "said Kevin Russell, a spokesperson for the Investment Property Owners Association of Nova Scotia.Rent control versus fixed-term leases

Nova Scotian advocacy groups and tenants have been pushing for rent control. In 2020, a two per cent rent cap was put in place by the province to prevent rents from soaring, in the midst of the COVID-19 pandemic. In March, the province announced that the rent cap would increase to five per cent, beginning Jan. 1, 2024, and extend to Dec. 31, 2025.

In April, an anti-poverty group called ACORN won its decade-long campaign to have Halifax regional council enforce a rental registry by-law. Landlords will have to list their properties in a database by April 1, 2024. It also gives by-law officers power to inspect rentals for needed repairs.

But, landlords have been using what advocates like Joanne Hussey refer to as a fixed-term lease ‘loophole,’ to get around the two per cent cap. When these fixed-term leases expire, which is often after a short term, tenants have no right or obligation to stay once it expires. Rents can be raised far beyond the rent cap, if a tenant wants to sign a new fixed-term lease. If a tenant has vacated, landlords can do what’s called a ‘renoviction.’ This is when renovations are used to justify a much higher rent for the next tenant.

CMHC data shows that vacant one bedroom units in Halifax cost an average of $1,369 per month, whereas occupied one bedroom units average at $1,219 per month. In January, CMHC reported that the 2022 “turn over” rate of all rental units in Halifax saw an increase of 11 per cent in rent, and two-bedroom units were increasing in rent by 28 per cent, as units were turning over from an outgoing tenant to a new one.

“This rent disparity might be from renovated turnover units or property owners adjusting rents to market value because of higher operating costs,” according to the 2022 CMHC Rental Market Report.

Russell believes the new five per cent rent cap should be higher so landlords can put revenue back into the upkeep of properties. He also supports fixed-term leases.

“Fixed term leases play a vital role in the industry, they allow landlords an opportunity to rent to people [who] don’t really meet the criteria of an application,” said Russell. “They might have a poor credit history … they may be new to the area … like any business, you want to be able to mitigate your risk.”

caption

"If people under 30 can't afford (rent) in the main peninsula, or downtown Dartmouth, and they're just moving farther and farther out," said Susan LeBlanc, the MLA for Dartmouth North which is located across the harbour from the Halifax Peninsula.While there isn’t comprehensive data that is public to show numbers and locations of all Residential Tenancies cases, there’s been some anecdotal evidence of a pattern. Susan LeBlanc, the MLA for Dartmouth North, has noticed a high number of Residential Tenancies applications for “renovictions” in her area. They are tied to fixed-term leases.

“Dartmouth North used to be the place where you could get a fairly affordable place to live,” said LeBlanc in an interview with The Signal.

“I’ve talked to people who are contractors who would say, ‘that work doesn’t have to be done, those units are in good shape,’ … the only reason the landlords want to keep people out to do renos is because they can bring them back in at double the rents.”

The Signal asked interviewees what would happen if young people continued to get priced out of Halifax.

“I think we'll see people who choose not to settle here, to start families here … we'll see the population demographic change, if people under 30 don't settle here, those are the people that we're counting on … to take over jobs for people that are retiring,” said Max Chauvin, the director of housing and homelessness for the municipality.

“People under 30 spend, invest in the community … they start businesses, we'll lose all of that.”

caption

"(There are) students who'd like to come to university and their barrier isn't they can't afford tuition, their barrier isn't they can't do the work, the barrier is they can't find a place to live," said Max Chauvin, director of housing and homelessness for the Halifax Regional Municipality at a community meeting on March 28, 2023.An ongoing saga between landlord and tenants

When The Signal requested an interview in a phone call to Jaden Lawen, his response was: “I have no comment.”

At the April 24 hearing where Lawen continued to represent himself, he said he wanted to live in the Quinpool Road suite with his friends because it's a short walk to Dalhousie University.

Barrie wasn't buying that explanation.

“This is our home, we’ve been here, we pay rent, we’re doing what we have to do … he lives with his parents in a four-bedroom, $1.8 million house,” said Barrie, referring to the custom-built Lawen family home in Fairview, which has five bathrooms.

At the April small claims court appeals hearing by phone, Lisa Jones, the legal aid lawyer who represents Barrie and their roommate, grilled the appellant about his father Louie Lawen who is listed as the director of Newal Property Investments Inc.

Jones argued that he was not pursuing the appeal in "good faith" as he lives rent-free and that his father's business the Lawen Group owns rental properties which he and his friends could access, instead of the Quinpool Road apartment.

The adjudicator Scott Barnett will email a final decision to all parties on May 8, 2023.

This story is part of a series in The Signal examining how and why Halifax is one of the most unaffordable Canadian cities for adults under 30 years old. Poor well-being is, according our research, a byproduct of the inability to cover basic expenses such as food and rent because of low wages.

About the author

Crystal Greene

Crystal Greene (she/her) is originally from Winnipeg, where she lived most of her life. She now lives in Kjipuktuk/Halifax with her toddler....